Elite Series pro Keith Poche created a versatile lure when he was a teenager that he still uses on tour today. Find out how the inventor of the KP Power Spinner rigs up — and then mops up the bass.

The darkly tanned professional fisherman paused when he walked out of the country convenience store and looked at the boat hanging on the back of his truck, a 21-foot Triton TrX Elite with a big 250-horse Mercury.

He shook his head gently from side to side, as if not believing his fortune.

“I can’t believe where I am. It’s pretty amazing. Growing up here fishing for fun; I never thought I would be coming back here as a pro, doing an article on fishing in Cane River.”

Keith Poche (pronounced PO-shay), a member of the coveted Bassmaster Elite Series, is listed on the organization’s website as being from Pike Road, Alabama, but he grew up in Natchitoches Parish.

I was with Poche to learn the art of using the lure he invented, the Keith Poche Power Spinner, which he usually shortens to KP Power Spinner. He was back in Louisiana to visit his family, including his brother Burt Poche Jr., who accompanied Keith to fish Cane River Lake.

Burt, owner of Poche’s Wood Specialties, is a custom cabinet builder who lives in Natchez, Louisiana, hard by the shores of the lake. “It’s so convenient. I fish it once a week.”

After launching at Shell Beach Ramp in the tiny settlement of Bermuda, about mid-way on the 34-mile long river-lake, Keith ran north and stopped at the outside of a big bend in the river, speckled with floating lily pads.

The inside of each bend usually has a shallow flat extending from the bank,” he explained. They assumed spawning fish would be using the flats.

Keith started with the lure he would spend the rest of the day using, a 5-inch green pumpkin Luck-E-Strike Chris Lane Pow Stik rigged with no weight and a buried hook to make it weedless.

The salt in the plastic worm and the added spinner provide enough weight to the worm to make casting it easy without extra weight, he said. (See “How to Properly Rig a Keith Poche Power Spinner.)

Burt started with a black and blue Gary Yamamoto Senko, later shifting to a black and blue Pow Stik.

Both added KP Power Spinners with hammered nickel Colorado blades. The spinners are also available in either hammered or smooth Colorado blades, or willow leaf blades in either gold or nickel, as well as in seven bright colors of Colorado blades.

The two men presented their lures by flipping, pitching and casting, depending on the circumstances. Besides the lily pads where they started, the lake offered them a variety of other habitats, including laydowns, residential docks and boat houses, grass beds and cut-grass clumps. Few standing stumps exist, as the bed of the lake is identical to the river bed it once was.

The speed at which the lures were fished was unexpectedly fast compared to how worms are usually fished. A normal retrieve was spinner bait speed with the lure running about 6 inches beneath the surface.

Occasionally, they paused the worm. When paused, the worm backed up while sinking due to the weight of the spinner on its back end. While sinking, the spinner kept spinning. Often strikes came during the pause and sinking, although most fish simply hammered it during a steady retrieve.

“This is a good search bait,” said Keith firmly. “You can cover a lot of area, but with more finesse than a spinner can.

“Worms are proven fish producers. This rig allows you to fish a worm a little faster and cover more area.”

Bass hammered the worms regularly, although the bite was better in the many beds of lilies than on straight banks.

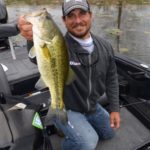

The lure was impressive, producing a sackful of bass for the pair. Keith’s professionally wrapped boat gave away to most other fishermen his professional status. Chatter with the anglers in other boats by the two friendly men revealed that most other anglers had boated just two or three bass at best. But the Poches’ success wasn’t due to them finding secret spots on the tiny river — everyone was beating the same bank.

Family is a big deal

The first thing one notice’s about Keith Poche’s truck and boat are large images on each side of his nephew, brother Burt’s son, Dylan Kyle Poche. He even has the youngster’s initials embossed on his boat’s windshield.

In January 2016, Louisiana’s competitive bass fishing world was rocked by the murder of the 18-year-old in a Sibley Lake boat launch parking lot. The youngster, a sophomore engineering student at Northeastern State University, was on the school’s fishing team.

“He was a natural born fisherman,” said Keith softly.

“He was a duck hunter and a bass fisherman. He was worse than me about fishing,” smiled Burt.

“He was a heck of a baseball player, too,” added Keith. “When my brother called to tell me that he wanted to be a tournament fisherman, I was hesitant for him. I knew how competitive and expensive it is to tournament fish.”

“But he quit baseball in high school to fish,” Burt took over for his brother. “In college he fished in the local sanctioned tournaments. At his death, he was entered into the Bass Pro Shops Bassmaster Central Open.”

“That’s how you qualify to get into the Bassmaster Elite Series,” explained Keith. “That’s where I fish.

“His death has brought the whole family together.”

The night before the two brothers hit Cane River Lake, they joined their 66-year-old father Burt Sr. for supper at his home. The rugged individualist (“hardcore” is Keith’s term) traps hogs, hunts deer, raises a big garden, makes his own seasonings and cooks.

He outdid himself for supper — wild pork ribs, venison in onion gravy, beans and rice, corn on the cob, baked beans, smothered okra and potato salad.

Over supper, the two brothers laughed and reminisced about how they spent every moment they could on “the river.” Although they were eight years apart in age (Burt Jr. is older) the river exerted its magical effects on both of them.

And bass it was. To this day, neither cares a lick about fishing for white perch, bream or catfish.

Just bass, bass and more bass.

The lay of the lake

Cane River Lake is simply an abandoned channel of the Red River. Two hundred years ago it was a commercial waterway, heavily navigated to and from the south by steamboats carrying cotton and passengers to service the local plantation economy.

Historically, riverboat traffic was blocked beyond Campti, north of Natchitoches by a great raft of logs jamming the river that extended north to Shreveport.

Captain Henry Shreve (after whom Shreveport is named) undertook removing the log jam raft. When it was completed in 1838, something strange happened. Instead of the improved flow cutting the river deeper, it jumped its banks near Grand Ecore and cut an entirely new channel down to the vicinity of Colfax, where it rejoined the old channel.

Gradually, the old river channel shrank in size and was renamed as Cane River, with the new Red River paralleling it to the east. In the early 1900s, earthen dams were constructed on the northern end of Cane River near Grand Ecore and on its southern end near Derry.

In 1949, a modern spillway was installed on the southern dam, essentially finishing what is now Cane River Lake. The present length of the lake is roughly 34 miles, with an average width of 340 feet and and average depth of 8.9 feet.

For fishing purposes, the river can be divided into northern and southern segments, with the Shell Beach Boat Ramp demarking the two sections. The northern segment is shallower, in some places only 3 feet deep, and waters are murkier.

The southern segment is deeper, up to 22 feet. It holds more grass beds, which in turn, keep the water clearer.

“The whole thing is good for bass fishing,” claimed Burt Poche, who fishes it regularly and lives on its shores. “But the fish can be picky, probably because of the amount of fishing pressure they get.”

Much of the shoreline north of the boat ramp, toward Natchitoches, is heavily developed residentially. Some are new mansions; others are time-worn old trailers and buildings dating from the 1950s. South of the ramp, the shoreline becomes less and less residential, giving way primarily to agricultural fields.

Besides the public boat launch at Shell Beach, another launch is located on Washington Street in Natchitoches, and a third one is at the spillway at the extreme southern end of the lake.

Signs are posted at each launch notifying that the completion of an approved boating safety class is a requirement for anyone to operate a powerboat on Cane River Lake.

The road to professional fishing

Every tournament bass fisherman harbors a dream of somehow, someday becoming a full time professional fisherman, with the apex being named one of the 108 Bassmaster Elite Series pros.

Keith Poche is one of them.

His route was almost accidental, although he was always an avid fisherman. “My brother Burt and I stayed out fishing,” he laughed. “When Burt was doing something else, I’d go wake my cousin C. E. Poche to go with me. We were 7 or 8 years old.”

But fishing had serious competition in Poche’s life — football. “I was agile, mean and athletic in high school football,” he said matter-of-factly. “I never left the field on offense or defense. On offense, I was a running back.

“I had an opportunity to play for Troy University in Alabama, but in my sophomore year there, I had a shoulder injury and couldn’t play.

“I brought my dad’s aluminum boat over and was fishing in a county pond named L & L Lakes. A guy in a Ranger, Daniel Sanders, saw me fishing in a sling. He felt sorry for me and asked me if I wanted to fish with him.

“‘You ever fished in a tournament?’ he asked. I said, ‘No man; I don’t know anything about tournaments. I just fish for fun.’

“He took me to a club tournament for Little Oak Bass Club. I was hooked the first time. I think the competitive side got me. We practiced and fished together for a year.”

With all the fishing, Poche was missing a lot of class, so he dropped out of college and went to work laying floors. He bought a 1992 model 17-foot fiberglass boat and started fishing tournaments in 2004.

He continued to fish club tournaments until Bassmaster started its Weekend Series, a bigger arena where an angler could potentially move up to the Bassmaster Classic.

“I was slowly working my way up,” said Poche. “At each step, I would work my way up. In 2008 I said, ‘Let me take this up a level,’ and signed up for the Bassmaster Open. I had a bigger boat by then, a 20-footer with a 250 horsepower engine.

“I finished almost last in the first two events and was so far out that I didn’t fish for the last one.

“I said, ‘I’m going to give it one more year. This is my hard-earned money.” I was on my knees. So in 2009, I signed up again, three events; $1,200 each.

“My first one, I finished 22nd and caught the biggest bass I ever weighed — 8 pounds, 11 ounces. The second one I came in 49th. The third one, held in Santee-Cooper in South Carolina, I took 6th place.

“I finished in 6th place overall. In those days they took the top 7 fishermen from the Open into the Elite.

“In Santee Cooper, I caught a 7 (pounder) and a 6 off one stump. The 7 threw the hook when my partner was netting it and it flipped into the net. If it hadn’t, I wouldn’t have qualified for the Elite and I wouldn’t be a tournament fisherman today.”

But the road was still tough. He had to quit his floor-laying job because his employer wanted him full time. In 2010 he took four out of eight checks fishing, but still lost money. He had only one sponsor. His brother-in-law Joel Mitchell helped him out with an offseason job.

Not until 2011 did he feel that he established himself as a professional fisherman. Since then he has been Top 10 Angler of the Year, has a 3rd place Bassmaster Classic finish, is a two-time Major League Fishing winner and has taken 4th and 5th place finishes in the Elite Series.