No spot in North America offers what waterfowlers find every season on Catahoula Lake.

There are few guarantees in hunting, but Catahoula Lake is as close as it gets for waterfowlers. The lake is an historical wintering area for ducks because of the amount of water and food available. There are a few things that ducks have to have: water, food and refuge. Louisiana has lots of water, and there is food scattered all over the state. And, sure, there are refuges here and there.

But Catahoula offers all three key ingredients in a single location. This vast waterbody has it all, including a federal refuge that provides protection from hunting pressure.

That’s why the 35,000-acre lake has traditionally drawn clouds of ducks.

“If a bird comes to Louisiana, it’s going to come to Catahoula Lake first, or if it doesn’t come to Catahoula Lake first, it will make it to the lake,” Catahoula Lake Guide Service’s Greg Andrus said. “We have 12 or 13 species harvested. We’ve got diving ducks and most of the puddlers.”

“There will be about 900 blinds on the lake,” he said.

Hunters bag thousands of gadwall, pintails, teal, ringnecks and mallards. That last species will just fill the skies at the end of the season.

“Two weeks after the season last year, you couldn’t put another mallard on the lake,” Andrus said.

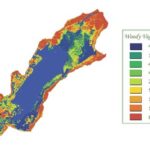

The lake is drawn down annually to encourage the growth of indigenous grasses, primarily sagittaria (duck potato), chufa, walteri millet and spangletop. The result is a virtual sea of duck groceries, which is then flooded just before the fall migration.

Andrus said hunting in these flooded grasslands can be frenetic, and the best way to find success is using floating blinds.

“It’s on pontoons,” Andrus said. “I can drive my boat up to it just like you drive into your drvieway.”

The blinds are simply camouflaged with pine boughs (oddly, that’s the brush of choice on the lake), and anchored in place.

“I have two poles on either side and in the front of the blind, and I use a 25-foot chain with a 150-pound anchor,” Andrus said.

And east-west positioning is the preferable setup.

“That way, my shooters aren’t shooting over each other,” he said.

However, if needed, the blind can easily be adjusted to keep hunters shooting with the wind and maintain safety.

“I just have to pull the poles and adjust the blind,” Andrus said.

His decoys stretch along a northeast to southwest line on either end of the blind.

“Our prevailing wind on that lake is a northwest wind,” Andrus explained. “Putting out my decoys in that spread means the ducks are usually landing on the west side of the blind.”

Calling is a must in these open-water conditions.

“When I first see a group of ducks, I’ll use a mallard call and switch to a pintail whistle,” Andrus said.

When ducks respond, peeling around to take a look at the spread, Andrus tones down his calling.

“I soften my call up and do a little three-note call: unnn, unnn, unnn,” he explained. “I call it my hurry-up call.”

What he rarely uses is a feed call.

“When do I hear that duck feed calling? In the air,” he said. “So I’ll very seldom use a feed call.

“Instead, I use an elongated chuckle.”

Catahoula Lake Guide Service clients wanting to concentrate on puddle ducks like teal, mallards and gadwall often are moved into the flooded willows. Here, they find a much different setup.

First, the floating blind is replaced with a fixed four-man pit blind.

“I’ve got a pothole cut out of the brush that’s probably about 1½ acres,” guide Jason DeWitt said.

The fact that the blind can’t move isn’t a real issue because wind direction isn’t a concern off the open waters of the main lake.

“The ducks are really coming in from feeding and looking for somewhere to rest,” DeWitt said. “Those teal buzz you; they come in right above the hawthorns, and they’re there before you know it.”

Other ducks, primarily mallards and other puddlers, come in higher, but don’t really need much coaxing. So DeWitt might call a couple of times to get the birds’ attention, but then he lays off.

“Usually, they’re either coming in or not,” DeWitt said. “It’s all about the spot.”

His dekes are placed in bunches in front of the blind.

“It’s not really a pattern,” he said. “I just put them out in groups — the teal together, the mallards together and the pintail together.”

All told, DeWitt uses about 400 dekes, with each species group separated by 4- to 5-foot lanes.

“I have an opening in front of the blind for the birds to land in, and the decoys only go out 40 to 45 yards from the blind,” he explained.