Why are Louisiana waterfowl hunters seeing and killing fewer ducks every season? There’s no single reason, but there is one that can be addressed.

With a new waterfowl season on the horizon, Louisiana duck hunters are waiting for the arrival of this year’s crop of birds, hoping they won’t be as frustrated as they have the past few seasons, when an increase in the number of ducks and geese over 50-year goals hasn’t translated into better-than-average hunting success.

Larry Reynolds, the waterfowl program manager for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries has data substantiating the lack of harvest, including 2018-19 numbers he said were the second-poorest in the past 15 years.

“On (Pass a Loutre, Pointe Au Chien, Atchafalaya, & Salvador WMAs), Louisiana duck hunters averaged only 1.9 ducks per hunter,” he said.

The apparent healthy waterfowl population and subsequent drop in Louisiana’s harvest numbers begs the questions, “Why?” and “What can local hunters do to fix the decline?”

As with most complicated problems, there isn’t a single linch pin that, if adjusted, would correct the problem. Rather, Louisiana’s waterfowl hunters are facing a barrage of changes that impact the numbers of wintering waterfowl in the state.

Climate change

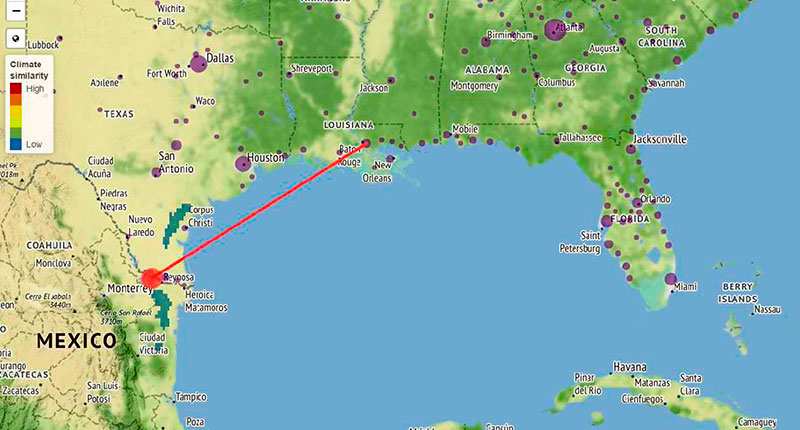

Although the phrase has been ridiculed more than Donald Trump at a Green New Deal convention, climates do change. No matter the cause, changes undoubtedly have some effect on everything in the ecosystem. In Reynolds’ presentation to Flyway Louisiana, a study from the University of Maryland found today’s climate conditions in Baton Rouge are similar to the climate conditions in Ciudad Gustavo Ordaz, Mexico more than 60 years ago, when the north-south distance between the cities is more than 300 miles.

Birds of all types and species are wintering farther north, a change taking place across the entire northern hemisphere.

“We know its true all around the globe,” Reynolds said. “The same type of white-fronted geese we have here in North America are wintering hundreds of miles farther north in Sweden.”

Louisiana waterfowlers probably don’t need a study to appreciate the effect. The appearance of the whistling tree duck, aka “Mexican squealer,” is now commonplace on duck hunters’ straps. Obviously, these ducks aren’t coming to Louisiana for our corn production. Their emergence is a result of climate changes.

Wetland degradation

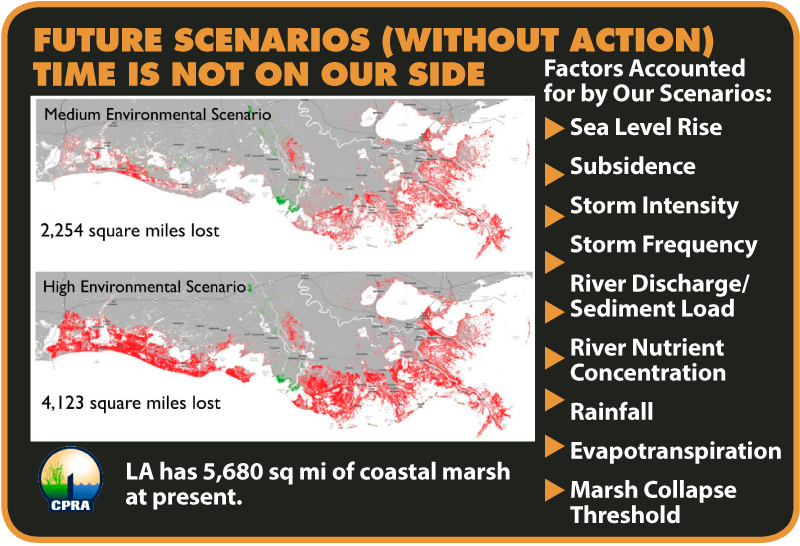

Another shocker: our wetlands are in a state of disarray. The Gulf of Mexico is continuously dissolving our coastal marsh, with about a third of our wetlands already lost since the 1930s. The remaining marsh is also being consumed by invasive pests like apple snails and nutria. Our native species are in another losing competition against non-natives like giant salvina, hyacinth and a host of others. Louisiana’s wetlands loss remains on a long-term trend of decline; it’s getting worse not better.

Remember the first “Duckmen” video? Phil Robinson and Warren Coco smashing greenheads, widgeon and grey ducks in flooded cypress swamp? That video was filmed in 1988 in the Maurepas Swamp.

Remember the first “Duckmen” video? Phil Robinson and Warren Coco smashing greenheads, widgeon and grey ducks in flooded cypress swamp? That video was filmed in 1988 in the Maurepas Swamp.

“If you went to that same place today, it is a solid mat of giant salvina,” Reynolds said. “There hasn’t been a duck in there for 20 years.”

Breeding success

A high percentage of waterfowl return to the same breeding grounds year after year. Conventional wisdom has been the same held true for wintering locations as well. Biologists are studying whether food source and water availability can alter wintering migration routes and populations. Are those patterns are merely seasonal adjustments? Or are the adjustments, in fact, long-term changes.

“We do not have any studies that explains the why behind changes in duck demographics,” Reynolds said.

“We do not have any studies that explains the why behind changes in duck demographics,” Reynolds said.

Anecdotally, wintering grounds that provide high-quality and abundant food sources ensure healthier adult ducks and geese returning to the breeding grounds. Healthier adults produce larger broods.

It’s conceivable that inverse is also true. That is, ducks and geese wintering in areas with low-quality habitat arrive at the breeding grounds less healthy and yield smaller broods. Thus, that segment of the waterfowl population declines slightly year over year.

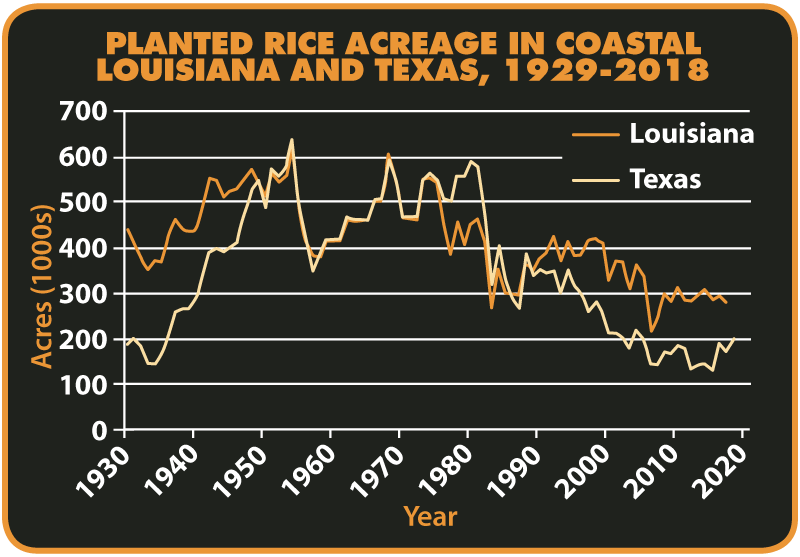

Corn and rice

At the same time Louisiana’s natural habit declines, our rice production is also dropping, off 30% to 40% from historical highs. While our production declines, agriculture efficiency has improved. Thirty years ago the rice harvest left approximately 400 pounds per acre; today, it’s about 70 pounds per acre. That means there is 20% less waste grain available for foraging waterfowl.

And while Louisiana agriculture is decreasing, the Midwest’s agricultural production is increasing, primarily due to the rise in popularity of ethanol. The corn-producing acreage in the United States has increased by millions of acres over the past 20 years, a scale so large that waste grain can be found on the ground as late as spring.

And while Louisiana agriculture is decreasing, the Midwest’s agricultural production is increasing, primarily due to the rise in popularity of ethanol. The corn-producing acreage in the United States has increased by millions of acres over the past 20 years, a scale so large that waste grain can be found on the ground as late as spring.

“Species like snow geese are actually feeding on corn during their spring migration,” Reynolds said.

The cornerstone of the corn issue revolves around flooded, unharvest corn. The question Louisiana hunters want answered is; “Does flooding corn come at the detriment of the number of waterfowl winter in our state?” Due to spring and summer flooding, there will be certainly be less corn as a whole. That may or may not result in a substantial reduction in flooded corn, but the 2019-2020 season could be litmus test in answering some of hunters’ concerns.

Perception vs reality

Before you can fix a problem, you have to acknowledge that you have one. Louisiana’s average annual waterfowl harvest from 2010 through 2014 was 2.5 million birds. In 2017-2018, Louisiana duck hunters killed 1.1 million birds. We’re taking less than half the ducks we took five years ago.

But our reality isn’t seen as a problem from the perspective of our neighbors to the north, and they certainly don’t agree there is a need for a fix at all. In contrast to Louisiana’s take, hunters in midwestern states killed around 350,000 ducks last season.

“In Wisconsin, Indiana and Illinois, they had their best year in the last 10 year. They averaged 1.9 ducks per hunter,” Reynolds said.

It’s a stark lesson in perception. Midwestern states’ best average harvest is equal to one of Louisiana’s worst.

Where do we go from here?

Reynolds gets it; he’s a hunter himself and appreciates Louisiana’s waterfowl traditions and is an advocate for our plight.

“Our harvest has declined 60% in the last four years,” he said. “That’s why Louisiana hunters are angry and looking for reasons as to why hunting success has declined so much.”

Unfortunately, there aren’t any simple solutions to restore our waterfowl harvest numbers. Louisiana hunters can’t make an impact on the climate or the global supply and demand of agricultural products. But we can coalesce around a “my backyard” philosophy. The health of our wetlands is instrumental in the amount and diversity of waterfowl wintering here. Without them, we’ll end up nothing but open water and cook book full of dos gris receipts.

There is no sugar-coating it. With multiple seasons of below-average harvest numbers, our long-term wintering trend looks a lot like LSU vs. Alabama. But hope springs eternal, be it in the blind on opening day or “Geaux Tigers.”

Shoot ’em up.