Brood surveys indicate that the 2004 may be even better than last year’s.

Paul Ferrell had several good turkey hunts last year, but one stood out above the rest and will be forever etched in his memory.

Ferrell and a buddy were two of 30 hunters selected for a three-day lottery hunt on Sicily Island Wildlife Management Area in Catahoula Parish.

The first day of the hunt, Ferrell and his hunting partner decided to separate in order to double their chances of locating birds.

They walked ridges and

valleys on the hilly public area, and paid close attention to any activity or sign they saw or found.

Ferrell’s buddy covered many miles of the forest, but he struck out. Ferrell, however, a 20-year turkey hunting veteran, located four gobblers and was able to work them for the better part of the

morning.

“The birds would work, but they’d never come into range,” Ferrell recounted. “Finally they eased off.”

Ferrell did the same, abandoning the area to meet his buddy at the appointed time at the

reconnoiter spot. They discussed the situation and opted to move to an area forward of the

direction the turkeys were heading.

It proved to be a smart move. Two of the birds had taken a different trail, probably off to find lonely hens, but the other two eagerly answered Ferrell’s calling.

“They both came into range, and my friend killed one,” he said.

That was obviously what they had hoped would happen, but it ended the hunt for Ferrell’s friend, since lottery hunters are limited to one turkey per drawing. So Ferrell was left to hunt on his own.

“The next day it rained all morning, so I was washed out,” he said.

But weather conditions improved, and on the final day of the lottery hunt, Ferrell went to a different section of Sicily Island, and immediately found two workable gobblers.

The birds responded like champions with their vocal chords, but they wouldn’t venture a pass close to Ferrell’s position.

Eventually, one of the gobblers moseyed off, but the other stayed around, too aroused by the unseen hen calling from the bush to leave but too cautious to get any closer.

Ferrell remained undaunted, and called when his instincts told him to and kept quiet when he felt he needed to raise the bird’s curiosity.

Finally, his patience paid off. Around 10 a.m., the gobbler had had enough of the game, and stormed in to give the hen a piece of his mind and put her in her place.

Like a great Greek god on a mountaintop, the mature gobbler strutted to the crest of a ridge 30 yards from Ferrell.

The hunter’s shotgun roared, and the bird fell.

But this wasn’t just any ol’ turkey. The mature gobbler had a 12-inch beard and 1 1/2-inch spurs, and weighed in at 23 pounds. The trophy tom’s score placed it in the top 15 ever killed in Louisiana.

Such a bird would have been a prize on private land that had been managed to grow trophies for decades. On public land, it was truly a turkey of a lifetime.

Not every hunt will be that good for every hunter this year, but Ferrell expects the 2004 turkey season to be a good one.

And he ought to know. For the last 8 1/2 years, Ferrell, 45, has served as the full-time regional director for South Louisiana for the National Wild Turkey Federation. He’s also the field supervisor for Louisiana and Texas, and spends much of his time doing “field research” during the turkey season.

“I think it’s really going to be a pretty good year,” he said in February as he geared up for the March opener.

Louisiana this year has a statewide opener on March 27, and that’s partially responsible for Ferrell’s optimism.

“I like the single statewide opener because it spreads the hunters out,” Ferrell said, explaining that a staggered opener concentrates hunters who travel to take advantage of opening days in the state’s different zones.

Also, this year, because of how the calendar falls, opening day will be later than it is some years.

“The peak of the breeding time may be over (by then) in some parts of the state, but that’s not always a bad thing,” he said. “The hens will get bred, go off and lay an egg and set a nest, and that makes those gobblers lonely. That makes them susceptible to hunters.”

There will also be a lot of competition among gobblers for hens this year because the hatch two years ago was a good one. That translates into more favorable opportunities for hunters this year, according to Fred Kimmel, the DWF’s upland game program manager.

“The 2-year-old gobblers are the easiest to kill,” he said. “They strut around the woods gobbling like crazy, looking to breed.”

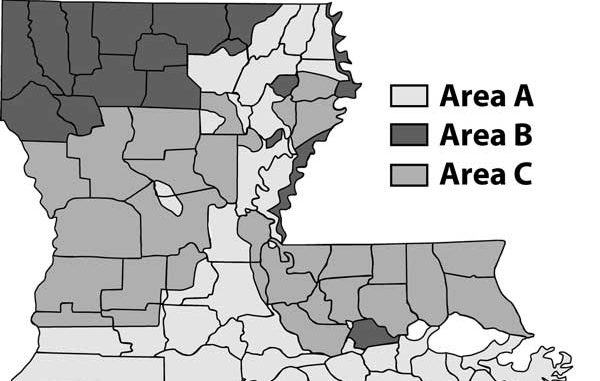

The hatch two years ago was particularly strong in the central, southwest and west-central parts of the state, according to brood surveys conducted by DWF biologists during the summer of 2002.

“That’s what we call the piney region,” Kimmel said. “It was very good.”

The northern delta area also had a strong hatch, but the northwestern portion of the state had only what Kimmel classified as a decent hatch.

Two areas that fared worse were the Atchafalaya region and the Florida Parishes. That continues a trend of deteriorating production throughout much of the Florida Parishes.

The reasons for that decline are probably legion, according to Kimmel, but three of the most likely culprits are urban sprawl, intensive timber management and farm-land abandonment.

“That area used to be dominated by small crop farms or dairy farms, and that type of habitat is good for turkeys,” Kimmel said. “They like open fields that aren’t exceptionally large.

“But many of those farms have been abandoned, and the land has been planted in pine trees. So you have a double-whammy there. Not only have you lost the open fields, but it’s been replaced by poor habitat.”

Kimmel said he also thinks the turkey population of the Florida Parishes may have been hit with a disease outbreak in the 1980s.

Whatever the reasons for the decline, Florida Parish hunters may want to consider abandoning their leases this season and hunting public lands in other areas of the state. Ferrell’s hunt last year proved that’s not such a bad proposition.

Louisiana has 600,000 acres of state-managed land available to turkey hunters, according to Kimmel. Add in the federal land, and the total balloons to more than 1 million acres.

“I’d say we have some pretty good public-land opportunities for turkey hunters,” Kimmel said.

Ferrell agrees. He spends much of his hunting time on Kisatchie National Forest.

“Kisatchie is underestimated by most hunters,” he said. “People don’t want to hunt there because they’re afraid of getting shot. I mean, there’s always a chance of that, but if you wait until late in the (season), you can have big sections of woods to yourself, and you can find lots of birds.”

Even if there are other hunters in the woods, Ferrell said most of them leave, with or without a turkey in hand, by 8 a.m.

“That’s the worst thing you can do,” he said. “For the first two or three hours after a gobbler flies down (from the roost), he’s henned up. He’s got lots of company, so there’s no real reason for him to leave and go find you.

“But then the hens leave, and he starts looking for love. Really, 10 a.m.-noon is the best time to kill a big gobbler. If you get a turkey to gobble between 10-12, there’s a real good chance you’re going to kill him.”

Many of the state WMAs are managed using lotteries to limit the number of hunters and thus heighten the experience for those who are selected. Others have open hunting.

But even still, turkey hunters don’t have near the competition for their quarry as do deer hunters.

Louisiana sells about 10,000 turkey stamps every year, but Kimmel estimates the actual number of turkey hunters statewide to be about 15,000 (hunters over the age of 60 or under the age of 16 and all lifetime license holders are exempt from the turkey stamp requirement).

Those hunters combine each year to kill about 10,000 birds, which is a remarkable number considering each hunter is limited to two birds per season.

The harvest last year was even higher, 11,000, according to Kimmel.

Given the strong brood survey from 2002, hunters may even top that number this year. For some, it’ll be now or never, since the huntable population may see a decline next year, Kimmel said.

“The brood survey last year was not as good,” he said. “That means there’ll be fewer jakes this year and, of course, fewer 2-year-olds next year.”

Brood success depends on a number of factors, but one of the most important is rain, according to Kimmel.

“You like to see a drier than normal April, May and early June — not a drought, but you definitely don’t want heavy rains,” he said.

Heavy or consistent showers keep turkey poults wet, causing increased mortality, Kimmel said.

This time period is crucial because the turkeys are so young. The median hatch date in Louisiana is May 12.

“That means half the turkeys will hatch before then, the other half after then,” Kimmel said.

After the birds have made it through the spring, their needs change, and rainfall is more tolerated, even desired.

“In July and August, you want above-normal rain,” Kimmel said. “You still don’t want storms or floods, but rainfall causes a lot of insect hatches and it makes the grasses grow, which puts more seeds on the ground.”

By the end of summer, the poults are half-grown, and are about the size of an average chicken, Kimmel said.

That growth rate slows, and by the spring, less than a year from when they were hatched, the male turkeys are full-grown and harvestable.

But most hunters will let the jakes walk, hoping to fill their season’s limits with two like the bird Ferrell killed on Sicily Island.

A true trophy.