The spoil banks of Louisiana’s marsh hold more than their share of bushytails.

Frank Tullar was the guy I hung out with in high school. Of course, the fact that I dated his sister might have been part of it. Nonetheless, we were friends, and his sister didn’t hunt squirrels.

Each fall, we’d tromp the woodlots adjacent to the farm fields that made up much of the landscape where we both grew up in southern Michigan. Frank was a year older than me; therefore, that made him smarter — or at least he thought so.

Hunting late one evening, with not much to show for our efforts, suddenly we both spotted a fox squirrel making a get-away through the oak- and maple-tree canopy above. In lightning-like fashion, Frank raised his shotgun, firing at the object that was more of a red blur than a squirrel.

The report from his shotgun bounced back at us like a ball off a wall at the edge of that woodlot, and faded behind us in the open corn stubble field. Strangely, as the sound faded, confetti gently fell from the sky settling like snow flakes all around us.

I heard the guttural cry, “Oh no!” from my friend as he dropped to all fours crawling on his hands and knees picking up pieces of shredded paper. Bending over, I picked up a piece of the confetti, and it happened to be a piece clearly marked $50 — as in President Grant, from a $50 dollar bill.

I busted out laughing with Frank groping on the ground repeating the words “oh no” over and over again. Frank’s words changed to “shut up” in a sort of psychotic crying laughter mixed in with a mumbling threat to kill me.

In an effort to hide his hard-earned money from a juvenile delinquent younger brother, Frank rolled it up and stuffed it in the barrel of his shotgun, where it couldn’t be found.

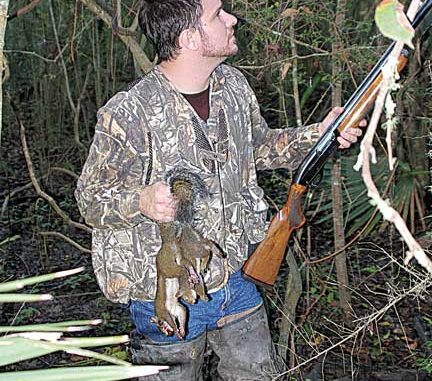

Forty years later, as I stood next to my eldest son Jason last season, I couldn’t help but smile as a panicked grey squirrel lit through the live oak canopy above us. The mixed live oak, hackberry and myrtle trees that buttressed the edge of the marsh near Cote Blanche Bay were the perfect backdrop, reminding me of those woodlots back home.

Like Frank, in lightning-like fashion, my son raised and fired his shotgun. Before the grey could put enough foliage and bark between us, a load of Winchester high-brass No. 6s raced through the air, guided by laser accuracy. Partially whacking the side of a 6-inch diameter branch the squirrel was utilizing as a thoroughfare in the process, it was no contest — the pellets won out.

There would be no confetti on this outing, just a plump grey falling as straight as a string on a plumb bob into the palmettos below. But there would be laughter, mostly from good-hearted jesting between father and son.

The coastal parishes are possibly the most overlooked and under-hunted areas in the entire state of Louisiana when it comes to squirrel hunting. What’s more, it’s not due to any lack in numbers of the bushytailed, tree-dwelling critters. On the contrary, in all actuality, marsh canal banks, tree-lined bayou banks, pipeline crossings and cypress swamps in this region are teeming with squirrels.

Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries biologist Fred Kimmel feels it essentially boils down to is personal preference and differences in hunting activities that people have in one geographic location to another.

“There, I’m sure more than anything, is less tradition,” he said. “People in that part of the world are more in into waterfowl hunting and rabbit hunting, and just overlook squirrel.”

What squirrel hunters are overlooking is limits. Several seasons ago, my father-in-law kept tract of his take at the end of the road locals simply refer to as Bayou Sale, harvesting 98 from the lease we shared.

What hunters won’t harvest is a high number of fox squirrels, as there tends to be higher concentrations of the grey variety. Bag limits tend to be mixed, with grey squirrels typically outnumbering fox three and sometimes four to one.

Habitat along the marsh differs from that in the red dirt regions of the state, where taller hardwood canopy and piney woods are better suited for fox squirrels.

“Grey and fox squirrels clearly overlap, but the habitat is a little bit different,” Kimmel said. “They do seem to have preferences. You tend to see the greys where you’ve got a little thicker mid-story cover of thicker canopy. You tend to see foxes in more open woods that have less of the mid-story type stuff — commonly in mixed pine and hardwoods.

“Generally speaking, because you’re talking about areas that are brushy and having mid-story stuff, you don’t have a dominant canopy. It’s an open type canopy, where you see more greys. For that reason, it may be a structural thing more than anything.”

That mid-story is what makes hunting greys somewhat of a challenge. Where squirrel hunters who stalk the tall hardwood and piney forests may look upwards at steeper angles, in the coastal regions they are careful to look just above eye level.

Ravaged by hurricanes with names like Andrew, Lili, Katrina, Rita and now Gustav, mast crop along the coastline is limited. Thick patches of myrtle trees, no taller than the peaks of a single-story dwelling, are favored forage locations for these marsh-dwelling squirrels.

In addition to myrtle seeds and buds, they’ll eat hackberry tree buds, acorns from live oaks and pecans when available.

“If you have live oaks and some other oaks side by side, probably the live oak wouldn’t be their first choice,” Kimmel said. “But in those areas down below, along the spoil banks, live oaks are all you have, and that’s what they are going to eat. But they’ll eat fruits, berries and soft mast. All of those kinds of things are going to be part of their diet. They’ll even consume bird eggs, so they’re pretty opportunistic.”

Both the grey and fox squirrels from the region tend to be smaller than their bigger cousins in other areas of the state.

“Greys are considerably smaller, but we have a lot of variation in fox squirrels,” Kimmel said. “You’ve got what we call ‘chuckle-heads’ that you find in the northwest part of the state. You’ve got some variation across the state that tends to be smaller than those. But the ones you see in the Atchafalaya swamp and places like that are still bigger than the biggest greys but smaller than the biggest fox squirrels.”

One of the difficulties with hunting spoil banks that are grown up with thick understory and mid-story canopy is traversing the terrain undetected to effectively still hunt.

Elmer Bournadou from Centerville, now in his late 70s, tells how he used to hunt squirrels.

“We’d use a pirogue so we could be real quiet, so we could slip up on him,” Bournadou said. “You can hear squirrels popping those seeds on the myrtle trees. You have to be real quiet — you got to be able to hear that. It takes a while for him to move, and it’s got to be in a place where you can see through that thick stuff along the bank. You do it by ear and sound. Once you pick up that popping, he’s got to move — he’ll move. That seed cracks. Those little greys get into that. And that’s a good-eating little squirrel.”

Grey squirrels along canal banks and pipeline rights-of-way, where long stretches of mid-story cover exists, often alert one another of pending danger. Greys will bark out with a repetitive “chuk-keee-chuk-keee” sound, and lay flat as they can to branches without moving. When the “chuk-keee” alarm is made, soon afterwards others will sound the same alarm farther down the canal.

When the alarmists have made you, the best thing to do is to simply stop, find a little cover and wait, giving the squirrels time to settle down. In those early moments of sunup, when squirrels are most active foraging, they’re memory seems to fade quickly. The urge to locate breakfast seems to take over their better senses. If you can be patient, they’ll start moving through the low canopy, and you can return to still hunting them.

Both fox and grey squirrels in the marsh respond to a call well. There is something irresistible to another squirrel barking, where quite often they have to come and investigate the sound. The first give-away that you pick up is a swooshing tail as they climb to an elevation to give themselves a visual advantage to fulfill their curiosity and get a look at the interloper.

Calling also works well in the marsh simply as a way to locate squirrels even if they don’t come running to investigate. You’ll hear fussy bushytails bark back at you, where you can pinpoint their location to make a quiet stalk. Skilled hunters who call squirrels are sure to place a limit in a black iron roasting pot.

Because of the mid-story canopy and thicker cover, oftentimes all hunters will get is a glimpse of a fleeing squirrel, especially in early season when foliage is thickest. Because of that thick leafy cover, 12-gauge high-brass loads of No. 6 shot are not unreasonable, even though squirrels aren’t hard to kill.

However, that being said, youngsters shouldn’t be dissuaded from using their .410 and 20-gauge shotguns with the thought bigger is better at cutting through the cover. It’s all about getting them out to have some fun. It’s important for youths to be comfortable with what they are shooting. Besides, the abundance of squirrels in the marsh provides plenty of action and opportunities for redeeming themselves if they happen to miss.

Wooded areas in the marsh that hold good populations of squirrels, though thick with mid-story canopy and cover, can be less noisy to still hunt as compared to upland wooded areas. The moist soil and overall dampness from dew tends to conceal the sound of a soft-stepping squirrel hunter. Even with leaves falling daily, they lose that dry crackle sound when stepped on because of the moisture.

In that regard, perhaps it’s more forgiving than traditional places squirrels are popular to hunt. However, it doesn’t mean you should neglect your hunting skills when stalking.

*********************

I helped Frank pick up every piece of confetti we could find that day in the Michigan woodlot — many by flashlight well after dark. We went back to his house, and fitted and taped $50 bills until we reasonably had the shredded legal tender together.

A bank teller, the next day with raised eyebrow, replaced four tattered 50s with what looked like freshly minted bills. Because we were able to piece together clearly marked serial numbers, the teller made good on Frank’s error in judgment, suggesting a safer place to save money if he wanted to open an account.

Thirty five years later, each time I enter the woods to squirrel hunt, I can still see that confetti when a squirrel rockets through the trees.