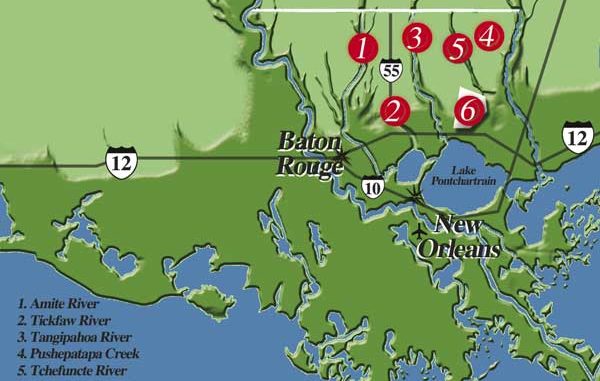

Florida Parish streams and rivers have historically offered some of the best fishing in the state. Will they ever again?

Going on two years after Hurricane Katrina, fishing in the Amite and Tickfaw river basins is still in recovery mode — notwithstanding a countryside fish-restocking scheme set in motion by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries even while department personnel were heroically engaged in search-and-rescue missions in flood-stricken New Orleans.In both areas, return to pre-storm conditions has been painfully slow.

It does little to ease the impatience of Florida Parish anglers to observe that even now, 15 years after Hurricane Andrew, a sister basin — the Atchafalaya — has not fully rebounded from that storm’s havoc despite ongoing comprehensive fish-restocking efforts.

Energetic fish- and habit-restoration projects by LDWF are also under way in the southwest parishes whose streams, bays and lakes were crippled by Hurricane Rita. There, too, angler fortitude is being tested.

In the southeast, the fly in the recovery ointment of the Amite and Tickfaw basins is loss of grass beds in the shallows. Since big fish eat little fish, the success of restoration programs, whether by man via hatchery stock or by natural distribution through mother streams, depends on the existence of shoreline aquatics to provide immediate cover and future nesting grounds for introduced hatchlings.

Freshwater fishing in the eastern basins was hit harder than anyone imagined at first, what with shocked attention focused on the New Orleans and Mississippi Gulf Coast disasters. Even though the hurricane only sideswiped the western rim of Lake Maurepas, prolonged saltwater intrusion dispersed some fish, killed many others and saturated shoreline grass beds, destroying natural fish habitat on a broad scale.

Strange things happened in the aftermath of the storm. Imagine the surprise of fishermen on Blind River, famous for largemouth bass, when they worked their way down to where the river flows into Maurepas and began catching speckled trout and redfish on bass lures.

The incidence at the confluence of Blind River and Lake Maurepas recalled the dual action at the tailwater of the Tchefuncte River, where it merges with Lake Pontchartrain. Mixed creels of black bass and speckled trout taken on the same lures, along the same banks, have been an attractive feature of Madisonville fishing camps for many years.

Some anglers doubt the likelihood of Blind River becoming a permanent mixed-creel watercourse, pointing out the buffer zone of Pass Manchac, which keeps saline Pontchartrain and its fish varieties from intruding basically freshwater Maurepas. Historically speckled trout, even tarpon, have been caught in Pass Manchac, but only as far west as the present-day 1-55 crossing.

Prevailing opinion leans toward the historical boundary. As the allure of mixed creel action fades with time, the notion of a large body of salty water lying at the foot of a really good sweet-water fishing river vulnerable to east winds becomes less and less acceptable.

While there were some downed trees in addition to floods in populated lowlands in Katrina’s wake, nature buffs were happy to see the photogenic bald cypresses showcasing Blind and other rivers didn’t have wind damage severe enough to diminish the region’s fantastic eye appeal. Many parishes in the Bayou State feature picturesque waterways enjoyed equally by sportsmen and pleasure boaters, none more than the Floridas. World-class recreational rivers Amite, Tickfaw, Blind, Natalbany and Tangipahoa collectively define the term scenic waterways. And scenery is a big part of fishing in the Florida Parishes.

Bayou Barbary, an Amite River tributary about 10 miles east of French Settlement on Highway 444, comes to mind. The bayou is locally called family friendly.

Fish can readily be caught by youngsters as well as grownups. An earthworm dangled from the end of a cane pole is as apt to snare anything from a bluegill, goggle-eye, crappie, black bass or catfish as fancy gear is. The on-site bait and tackle shop does not have rental boats, so it’s a bring-your-own-fishing-rig operation. Launch fee is under $5. Fly rod and popping bug action is progressing, but better catches of panfish are made in 4 to 5 feet of water using crickets and worms under sinkers and corks.

The destruction of aquatic vegetation, especially coontail grass, was punishing here. Ordinarily the frilly stalks grow in paddies on shallow banks providing sanctuary for prey fish, hunting ground for predators including black bass and focal point for baitcasters. Rainfall on the upper Amite watershed has helped sweeten water in the lower reaches of the basin; patches of coontail are reforming. These comebacks are of particular interest to Barbary gamefishermen, who’ve taken largemouths up to 8 pounds there in past seasons.

Tucked away in the woods, partly hidden from highway view, Barbary is comparatively small — just a mile and a half long — but it has an impressive history. Before the Civil War, it was the center of a sawmill, cotton gin and shipyard. A schooner built at Barbary boatworks made weekly trips to New Orleans delivering cotton along with pine and cypress lumber, and returned with vital supplies for the bustling community.

A column of soldiers left from there in early 1800 to join other troops in a successful assault on the Spanish fort in Baton Rouge.

Settlers in later days, as townspeople do now, surely fished among the ageless shoreline cypress trees in their time off from work. Conceivably, sailors on Union gunboats did the same in their off-duty moments, since the entire Lake Pontchartrain/Lake Maurepas sector of the Gulf Zone was patrolled by Northern forces during the War Between the States.

Looking hopefully ahead to spring and summer fishing, barring another major storm, the annual mayfly hatch will return in its usual frenzy.

For years the news, “The caterpillars are out,” has been a call to arms for Florida Parish bream fishermen. Emerging larvae gorge on leaves of bayouside tupelo gum trees. Stuffed, the worms plop to the surface below, and are swiftly snapped up by waiting bluegills, who also attack deftly presented artificial lures to the delight of fly fishermen.

Bayou lore has it if 10 nymphs fall wiggling to the water during the hatch, two might live to become adult mayflies. It’s arguably as close to guaranteed success as panfishing ever gets, and made Carolina Bluegill Wigglers a household name in fly-fishing circles.

This spring, though, the numbers were reversed. There seemed to have been more leaf-eating caterpillars than there were bream in turn to eat them. Now it all depends on the weed beds under the overhanging tupelo gums and cypresses. When the habitat returns, so will the fish — no doubt in their pre-storm numbers and varieties.

Blood River, 9 miles north of Barbary at Killian, presents the same black bass, bream and sac-a-lait opportunities in a similar setting: winding waterway with gently sloped, grassy shorelines presided over by cypresses and water gums.

Access is a short boat ride to the right of the public-launch facility on the north side of the new Tickfaw River bridge. A tributary of the Tickfaw, Blood River has a heritage of its own involving a different kind of fish — a shark. A number of years ago, a great white was captured there. It was such a rarity — an oceanic fish so far inland, in fresh water — that skeptics were invited to view the beast mounted and displayed on the wall of a prominent business establishment in Springfield.

That a great white shark, capable of detecting blood in water leagues away, should leave the Gulf of Mexico, travel across Lake Pontchartrain, through Pass Manchac, across Lake Maurepas into the Tickfaw River, bypass Natalbany Bayou and zero in on Blood River was the coincidence of the month.

The broad rivers and secluded creeks of the Amite basin must have impressed even 17th-century navigators Iberville and Bienville, who viewed Louisiana in its pristine glory. It can be supposed the intrepid explorers beheld the vast, bayou-laced swamp roughly northwest of New Orleans some 300 years ago, and marveled at it, as did resident Indians hundreds of years before them.

Vestigial streams pass along that self-same wilderness aspect to today’s voyagers spiced with storied guideposts that tweak the imaginations of visiting fishermen, hunters and pleasure boaters. For instance, why Bear Island and Alligator Bayou are so named presumably is in recognition of the animals pioneers encountered in those particular habitats.

But what is the origin of Horse Bluff, a boat landing on Tickfaw River? The Spanish had a significant military presence in the region at one time. Is it possible stray mustangs from their cavalry once grazed there?

Blind River is another place that evokes the question of how it got its moniker. There is no question, however, about its popularity among black bass and sac-a-lait fishermen, whose numbers have increased dramatically since the Diversion Canal was completed.

The drainage project led to new canal-bank boat ramps off Highways 16 and 22 in the French Settlement and Head of Island townships. (Expect launch fees of $5 weekdays, higher on weekends and holidays.) At the moment, fishing reality does not match up with good boating facilities.

But sportsmen are loyal to streams they enjoy fishing whether or not every trip is successful. A lot of patience and a little bit of philosophy comes into play when nature shows its ugly side. Judging by activity at boat landings these days, Florida Parish habitues, accustomed to vigorous action, know fishing isn’t up to par yet, but they ride the bayous anyway and try favorite spots to see how the recovery is coming along.

Designating a queen of recreational rivers in looks and utility is a daunting task considering the likes of, say, the superscenic Tchefuncte River at Madisonville. The Tickfaw at Killian, playground of anglers, yachtsmen and runabout enthusiasts, and the mighty Amite at Port Vincent would be candidates.

While a riviera atmosphere prevails at the major boat landings on summer weekends, on a day-to-day basis, fishing trumps all other water sports.

The fishing genre has been grandfathered down through families further back in time than the great North-South conflict, to the late 1700s when Spanish general Galvez, governor of the Louisiana Territory, established a colony of Canary Islanders between the Amite River and Bayou Manchac.

The settlers highly praised the excellence of Amite River catfish. However, they questioned the perception of the early French explorers who named the waterway “Amitie” — meaning friendly. Aside from the tasty catfish it produced, the river was anything but hospitable to the colonists, who tried farming but had their spring crops periodically washed out when the river overflowed its banks.

Because of the capricious river and hordes of swampland mosquitoes, which spread the fever, the original settlement, today’s Galveztown, was bandoned by 1810.

Centuries later, the unique flavor of Amite River catfish is still being praised by seafood lovers far and wide.