Ciguatera, a tropical toxin that invades fish flesh, is showing up off the Louisiana coast, and it’s making people sick.

Louisiana folks love to eat fish. In spite of the modern hype to make catch-and-release fishing politically correct, we relish bringing our catch home for a feast. After all, if the Almighty didn’t want us to eat them, he wouldn’t have made them taste so good, right? Louisiana fishermen unflappably kept eating their catch right through the 2001-02 high-amplitude media blare on mercury in Gulf of Mexico fish, led by the Mobile Register newspaper. Now, to challenge us further, news comes that some offshore fish may contain ciguatera (pronounced sig-wa-TEHR-a), the mysterious tropical fish toxin.

Until very recently, most experts stated flatly that ciguatera did not occur in the northern Gulf of Mexico. No confirmed reports of ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP) were on record, and the soft muddy bottoms and turbid waters of the northern Gulf were considered unsuitable habitat for Gambierdiscus toxicus, the organism that produces ciguatera. CFP was considered a malady of the tropics, particularly the Pacific and the Caribbean.

Then in March 2007, a Galveston, Texas, couple became ill with typical CFP symptoms after eating a 34-pound gag grouper caught at the Flower Garden Banks, offshore of the Louisiana-Texas border. The woman was hospitalized for 13 days.

Then in July 2007, eight cases of CFP were confirmed from the New Orleans area. The diners were at a country-club dinner function, and had consumed marbled grouper, again caught near the Flower Gardens National Marine Sanctuary. The affected diners’ symptoms appeared 2 1/2 to 12 hours after consumption of the fish. None of the cases sought medical attention.

In the fall of 2007, these were followed by multiple CFP cases in St. Louis. These cases were linked to a 60-pound amberjack landed and processed in Louisiana and served at several restaurants in the Missouri city.

Then, two more cases of CFP appeared in Washington, D.C. The offending fish in this case was either a marbled or a yellowfin grouper. The fish involved in the St. Louis and Washington incidences were also caught near the Flower Gardens National Marine Sanctuary.

The Flower Gardens National Marine Sanctuary contains two major and one minor flat-topped, underwater “miniature mountains” that rise to within 50 feet of the water’s surface 100 miles south of the Louisiana-Texas border. Many of these unique geological features, called diapirs, occur off the Louisiana coastline. Geologically, they resemble the salt domes found on land on the central Louisiana coast, but they are underwater. The eastern-most one is the famed fishing destination commonly called the Midnight Lump.

Because the Flower Gardens reach so near the surface of the water, they are crowned with true tropical corals. This, and the fact that they are in the pathway of currents from the tropical Caribbean, means that the Flower Gardens also hold many tropical fish species that are uncommon elsewhere in the northern Gulf. The Flower Gardens are the northern-most coral reefs in the continental United States.

While CFP had not been recorded in the northern Gulf before 2007, Gambierdiscus toxicus had been discovered in the area in 2003 by Texas scientists. The organism needs hard surfaces on which to grow, so the researchers looked for it at six offshore oil platforms, and found it at all six.

Twenty Texas barracuda were also tested for the presence of ciguatoxins in the flesh. Two of the fish had low levels of the toxin present. However, barracuda are highly transient, and have been recorded to move 600 miles across the Gulf. The two fish could have as easily migrated from another area with the toxin in their bodies as to have accumulated the toxins in waters offshore of the northern Texas coast.

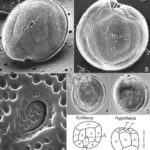

Gambierdiscus toxicus has a very descriptive scientific name. It was discovered in the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia of the South Pacific. It is shaped like a discus, and toxicus refers to the toxins it produces. It is classified as an armored, marine, benthic dinoflagellate.

Dinoflagellates are commonly regarded as microscopic, one-celled algae, but are a weird group of their own. They are both plant-like and animal-like. Some do indeed photosynthesize, but others are predatory and eat other organisms. Their bodies are armored with cellulose, the stuff of wood and trees, not algae.

Unlike typical algae, dinoflagellates can swim, using two whip-like tails called “flagella.” The longitudinal flagellum extends toward the rear (if there is such a thing on a dinoflagellate), and the other one, called the transverse flagellum, is set at a right angle to the first one. The longitudinal flagellum is used for steering. The transverse flagellum does more work in moving the organism, giving it a spinning motion. The Greek word “dinos” means whirling, and gives dinoflagellates part of their name.

Dionoflagellates play a big part in marine food chains, and more. Dinoflagellates cause paralytic shellfish poisoning in cooler temperate waters and red tides in warmer waters, as well as ciguatera fish poisoning. All of these are toxic to humans in large enough doses. Red tides kill fish as well.

Ciguatera is different from red tide organisms in that it cannot float in the water column. Rather, ciguatera dinoflagellates must be attached to a hard surface to grow and multiply. Dead corals seem to be the ideal surface, although they will grow on other hard surfaces.

Ciguatoxins enter the food chain when small fish graze on hard surfaces where the dinoflagellate is growing. The ciguatoxins accumulate in the flesh of the fish (bioaccumulation) as long as the fish continue to pick it up in their feeding. Usually though, in these grazing fish, levels are quite low.

However, when these fish are eaten by predator fish and then these predators are eaten by even larger predator fish, much higher levels of ciguatoxin (biomagnification) can occur in fish flesh. Unfortunately, these are the fish humans like to eat — groupers, jacks and snappers.

In exception to the popular belief that it is deadly, CFP is rarely fatal. Symptoms of ciguatera poisoning may include nausea; vomiting; diarrhea; numbness and tingling of the mouth, hands or feet; joint pain; muscle pain; headaches; reversal of hot and cold sensation (such as cold objects feel hot and vice versa); sensitivity to temperature changes; vertigo and muscular weakness. There also can be cardiovascular problems, including irregular heartbeat and reduced blood pressure. Some individuals experience only a few symptoms, others experience many. Symptoms typically last days or weeks, occasionally months and, rarely, years.

CFP is a strange malady. Ciguatera symptoms have turned up in otherwise healthy men and women after they had intimate relations with a partner who has CFP. Breast-fed babies have developed diarrhea and rashes on their face after being fed by mothers with ciguatera. The toxin is obviously mobile within the body.

Ciguatoxins are colorless, odorless, tasteless and are not neutralized by cooking or freezing. In northern Australia, where ciguatera is common, two folk methods for detecting the presence of ciguatoxin in fish are widely accepted.

First, it is believed that flies will not land on fish flesh containing the toxin. The second belief is that the toxin’s presence can be detected by feeding a piece of the fish to a cat, as cats are supposedly highly sensitive to ciguatoxin. The only confirmed method of detection, though, is through lab tests.

In response to the 2007 CFP cases, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) issued advisories in February to seafood dealers, fishermen and the public. FDA advises that CFP is reasonably likely to occur from consuming snapper, grouper and hogfish caught within 10 miles of the Flower Gardens, and from barracuda and amberjack taken from within 50 miles of the Flower Gardens.

Dr. Robert Dickey, director of Seafood Science and Technology within FDA, is not an alarmist over the 2007 CFP incidences in the Gulf.

“I don’t suspect that it (CFP) is a growing problem,” he said. “The Flower Gardens are a unique area with special conditions similar to the tropics. Nothing else like them exists in the northern Gulf.”

Dickey adds that we can’t be sure that the 2007 outbreak was not due to migratory fish either, although he notes that if fish move away from an area with ciguatera, the level of ciguatoxin in their flesh gradually declines.

He also notes the scientific observation that ciguatera strains in areas farther away from the tropics tend to be less virulent than those in the tropics. The Flower Gardens are about as far away from the tropics as corals can grow.

Dickey says that FDA’s seafood laboratory at Dauphin Island, Ala., is now involved in more extensive sampling for ciguatera. Offshore platforms and other hard surfaces will be checked for the presence of the dinoflagellate.

More importantly, FDA has stepped up fish flesh sampling. Dickey says that in some initial work, 40 Flower Gardens fish of 12 species — amberjack, gag grouper, barracuda, jack crevalle, marbled grouper, red snapper, sand tilefish, scamp grouper, shark, snowy grouper, vermilion snapper and yellowfin snapper — were tested.

Ciguatoxins were detected in four fish, a barracuda, a sand tilefish, a marbled grouper and a scamp grouper. Only the scamp had ciguatoxin levels high enough to be over the threshold to likely trigger CFP in humans.

Dr. Roult Ratard, state epidemiologist for the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals (LDHH), is uniquely qualified to discus CFP. He is a native of Vanuatu, an island nation in the South Pacific, 300 miles north of New Caledonia and west of Fiji. Growing up and last living there at the age of 32, he has by his own count had CFP “five or six times.”

Ratard is nonchalant about the malady, noting that in areas north of New Caledonia, it is common for people to miss a day or two of work occasionally with “the scratch,” as CFP is locally called. Symptoms vary among individuals, Ratard notes, with his own most often involving gastric upsets, but very little tingling.

Ratard says fishermen should not worry too much now, as the Flower Garden events may be isolated.

“If it continues to be a trend, we will learn more about it and which species to avoid,” he said. “But if climate warming is occurring, we may see more tropical events like ciguatera.

“Right now, ciguatera in the Flower Gardens is unpredictable. In tropical areas, consuming certain species from certain areas will produce ciguatera every time. On the other side of an island, the same species will be free of it. Near other islands a short distance away, different species will have it.”

He says that people in the tropics have learned to live with it by learning which fish species from which areas are likely to produce CFP.

“It is highly predictable there,” he said.

Annu Thomas, the foodborne disease epidemiologist with LDHH, says that the best thing people can do to be prepared is learn the symptoms of CFP. If they suspect CFP, both because of their symptoms and because of having consumed a suspect species of fish, they should alert their physician about the possibility. Few doctors in Louisiana are versed on CFP symptoms and fewer yet would suspect the malady, since it has been so rare here.

While CFP cannot be “cured” and each case must run its course like a cold, its symptoms can be treated. Thomas says that patients should also be aware that they can get over CFP, but redevelop symptoms in the future.