Veteran Lafitte speckled trout and redfish guide Maurice d’Aquin took a break from cutting sheetrock and clearing debris from his house in early August, 2021 to have a look at what Hurricane Ida had done to some of his favorite fishing spots.

What he found stunned and upset him almost as much as the three feet of mud left by Ida he was trying to shovel and till in his yard.

“I went to a shoreline on the west end of Little Lake, a spot where I had caught nice redfish all spring and summer and it was completely gone,” d’Aquin said. “I went to the exact mark on my GPS where I was casting to redfish along a shoreline and had to go across about 700 yards of open water before my trolling motor even touched mud.”

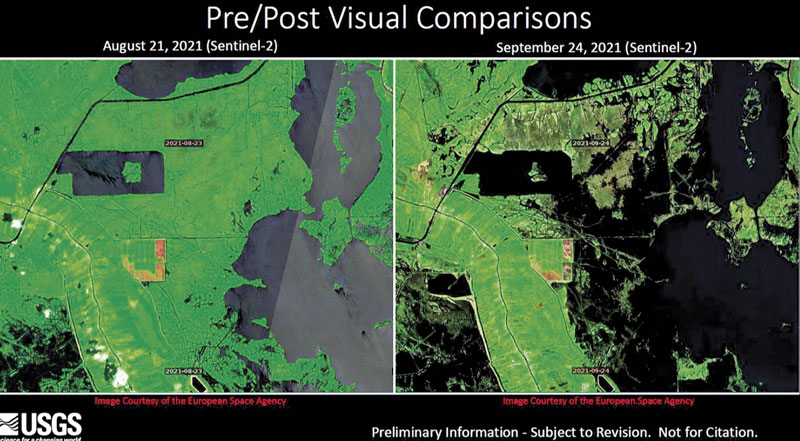

What d’Aquin has found by boat across the upper reaches of Barataria Bay, especially on the western and northern stretches of Little Lake, has been confirmed by aerial surveys by Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority and satellite images gathered by the United States Geological Survey. Hurricane Ida’s 150 mile per hour-plus winds scoured and decimated Louisiana’s coastal marshes in ways not seen since Hurricane Katrina removed an estimated 200 square miles in 2005.

Early indications are 106 square miles of marshes washed away or were displaced by Ida’s savage winds and 10-foot storm surge. The damage was spread across areas of Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parish east of the Mississippi River all the way west through Terrebonne Parish.

Bearing the brunt

The Barataria Basin bore the brunt of Ida’s fury. Marshes west and south of Empire in lower Plaquemines and Jefferson Parish that never recovered from Katrina were decimated again by Ida, taking what little was left in areas closer to the Gulf of Mexico and damaging recently-restored barrier islands. It’s the extensive damage in the northern reaches of the Barataria system, however, that has coastal wetlands experts and fisheries biologists most concerned.

“The whole Barataria Basin is only about 700 square miles, so to lose about 100 of those in one event like Hurricane Ida is significant and stunning,” said Brian Lezina, Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s Chief of Planning. “There’s a chance some of it will come back. The marsh can heal itself in time if the resources are there and vegetation regrows. But we won’t know how much will recover for a few years.”

Lezina said much of the marsh damage was in areas where organic materials and lighter silt make up the soils. Some of it was flotant, which is marsh that roots in decaying vegetation floating above the organic soils beneath. Ida scattered the uprooted marshes and light, organic mud, filling in nearby canals and fouling Lake Salvador and Cataouatche and shoving mud and grass into and under houses from upper Plaquemines Parish west into Jefferson and Lafourche.

Organic soil marshes and flotant are much more susceptible to wave action and erosion than marshes east of the Mississippi River and closer to the mouth of the Atchafalaya River that get annual sediment deposits with heavier clays and sand. They also lack the ability to repair themselves in the same way as areas that get sediment replenished annually from the rivers.

Resources to repair the marsh are often hard to come by in areas far removed from water and sediment from the rivers. Lezina said the CPRA and federal partners are evaluating the best options to try to repair some of the damage. He’s optimistic some regeneration will occur through a combination of natural processes and dredging projects.

“You have the Davis Pond Diversion nearby and the Intracoastal Canal that both can carry some water and sediment into the badly-damaged areas,” he said. “The sediments are being reworked all the time by waves and current. If the submerged vegetation grows back in shallow areas, it can help capture some of that sediment. And we’re looking closely at what resources can be directed into the area to help recapture some of the sediment.”

Effect on fisheries

Chris Schieble, a marine fisheries biologist with Louisiana’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, said the exact long-term effects of the dramatic marsh losses from Ida on fisheries production are hard to predict. However, as more organic soils and marsh “edge” are lost to storms, daily wave action and sinking of the land below the water line (called “subsidence”) that is eating away at the Barataria and other basins across Louisiana, fisheries production is certain to decline.

“It’s the organic materials and rotting vegetation called detritus that feeds the food chain in areas that don’t get a lot of sediment and freshwater input from the Mississippi River,” Schieble said. “Areas where the fresh and saltwater mix more east of the river and near the Atchafalaya River, the food chain starts with phytoplankton. But, in organic soils, the ones that look like coffee grounds, it’s the nutrient leeching out of the soil that makes up the base, feeds the forage fish and ultimately the predators like speckled trout and redfish.”

In the short term, marsh loss from storms can cause an increase in fisheries production and lead to more catches of speckled trout and redfish as fish orient to newly created and exposed edge habitats, shallow flats and washouts where tidal flows concentrate baitfish.

D’Aquin said he’s seen that firsthand in areas damaged by Ida.

“The storm opened up some new cuts along the shoreline in Lake Salvador where water is flowing in from the Intracoastal Waterway,” he said. “We caught a lot of redfish in the early fall in those washouts.”

In the long-term, however, the profound loss of marsh and organic materials will inevitably lead to a decline in fisheries production as nutrient levels drop and vital nursery grounds for juvenile shrimp, crabs, mullet and other forage is lost. Lezina and Schieble both said the Barataria Basin and other areas hardest hit by wetland loss over the last century will reach a tipping point where the benefits of new edge habitat created by storms will be outweighed by the habitat and nutrient loss and the conversion to open water.

“We may already be at that tipping point in the Barataria Basin,” Schieble said. “If you look at the time of year when Ida hit, it’s a time where we would be seeing redfish larvae recruit into the marsh and white shrimp developing in those marshes. The redfish might have been displaced or not recruited into that marsh at all. Ida’s path and destruction couldn’t have been worse for our recreational and commercial fisheries. Productivity and access have taken a big hit.”

Anglers have to adapt

The extreme changes in habitat have also altered where anglers and guides have had to focus their efforts since the storm. Many guides and recreational fishermen have also noted a change in the size and number of fish they’ve been catching.

Capt. Joe DiMarco has been fishing east and west of the Mississippi River out of Buras for more than three decades. He said the habitat loss and the fishing on the east side of the river is far different than what he’s seeing west of the river after Ida.

“The east side didn’t take nearly the beating we are seeing to the west where a lot of the smaller cane islands and humps where we caught trout last year are now gone,” DiMarco said. “We see some damage on the east side on the edge of Black Bay, but nothing like on the west. The storm seems to have pushed in a lot of big redfish too. Seems like we are catching many more 27-35 inch redfish way up in the marsh than we are 16-27 inch fish.”

D’Aquin said he’s having to relearn to fish his home waters around Lafitte in the same way he did after Katrina 16 years ago.

“Canals where we caught speckled trout during the winter are almost completely filled in and islands and peninsulas where we were catching trout and reds in the past are gone,” he said. “Just like after Katrina, we are seeing fish that are stressed and we are having to make adjustments. The fish and the marsh suffered just like the communities hit by the storm. But just like the communities are coming back slowly so are the fish. Each day gets a little bit better.”