If speck fishing were baseball, these two guys would be the 1990s version of Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire.

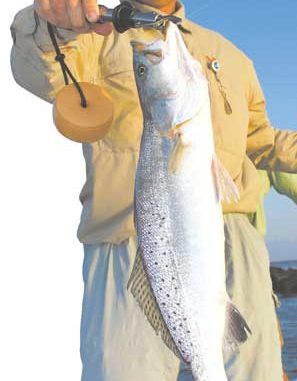

When does a speckled trout cross over from the indignity of school-trout status into the glory realm of trophy trout?

Chuck Miramon’s floor is considerably higher than most.

“Six pound speckled trout qualify as big fish for both Rudy and myself,” he said. “They get your attention, but they really don’t win anything.”

Miramon was cavalierly talking about speckled trout of a size that most anglers will never put in their ice chest in a lifetime of fishing.

Bold attitude. But Miramon and his regular fishing partner Rudy Hall can back it up. If trophy-trout fishing were major league baseball, the partners would be batting .400.

During 2003-2004, the LSU AgCenter’s Sea Grant Program and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries sponsored a program called Trout Watchers. Under the program, recreational fishermen were enlisted to remove and save otoliths (ear bones) of speckled trout 25 inches long or longer. By sectioning the otoliths and counting the rings in them, scientists were able to age trophy-size trout accurately. A 25-inch trout is nearly 6 pounds in weight.

About 80 of the best big-trout fishermen in Louisiana participated in the program, and Hall beat all of them in numbers of fish submitted during the two years of the effort.

Miramon is no slouch either. In 2008, he walked away with a brand-new fishing boat that he won in the Louisiana Coastal Conservation Association’s STAR Tournament for catching the largest speckled trout in his region of the state. Both men, STAR-fanatics, have had near-misses in winning the STAR in prior years.

They cautioned that this trip to the mouth of the Mississippi River to target big trout was a risky one. They were going to fish the late afternoon and much of the night along the rock and concrete jetty on the eastern side of the mouth of South Pass.

“We are gambling on one spot that we know holds big fish under these conditions,” explained Hall. “If they turn on, it could be a great trip; if not, it could be very slow.”

Fishing for big trout, the two men explained, isn’t a numbers game. You concentrate on spots that you have confidence will hold big fish. You fish these spots hard, sometimes for hours with little action, looking for a short bite that will produce a few big fish. Like Babe Ruth, you often either hit a home run or strike out. There aren’t many base hits in trophy trout fishing.

Hall and Miramon, who met years ago as neighbors in Madisonville, are more different than alike, but they make a strong fishing team. After meeting, they fished together in Southern Kingfish Association (SKA) competitions. Finding the SKA “too much work,” they dropped out.

Hall called their stint in the SKA productive.

“It was challenging,” he said. “It made you think about planning, charting, tides, techniques and so forth. It gave us a different perspective on fishing.”

They didn’t entirely drop out of fishing competitively, though. Both men take the STAR Tournament seriously. Hall dubbed it “… an extraordinarily challenging event.”

Miramon and Hall resemble each other in their passion for fishing, both starting at around 10 years old. Miramon, now 52, described his early lust for fishing as “insatiable.”

The 59-year old Hall still remembers listening to his maternal grandfather and uncles tell tales of using rowing skiffs and slaughter poles to fish Stump Lagoon out of Yscloskey.

The men began fishing speckled trout for size rather than numbers in 2002. But there, the resemblance between them differs. The avuncular, fair-skinned and nearly bald Hall, with his neatly trimmed moustache and eye glasses, is professorial in appearance. Miramon, olive-skinned with silver-streaked black hair, is definitely more laid-back (except when a rod is in his hands), and carries an ever-present grin that implies he knows a secret to which the rest of the world isn’t privy.

This trip to Venice was largely planned by Hall, an engineer who is a self-admitted “fish geek.” He has logged every fishing trip and every detail of each trip the two men have made for over 20 years. Miramon said he keeps a log too, but ruefully admited that “it isn’t as detailed” as Hall’s is.

This trip was patterned completely on a trip made in 2007, near this same date in the calendar and under the same tide and river conditions. The trip produced 30 quality speckled trout and the added bonus of 20 pompano.

This trip was planned for late evening and into the night to take advantage of a low tide. During high-tide conditions, with the Mississippi River this high, fresh muddy water from South Pass spills over the rocks of the jetty along the extent of the jetty.

This forces the murky freshwater layer that lies over the clear green salty waters deeper, making fishing much more difficult. At low tide, the muddy river water is shunted mostly out the end of the pass, and fishable water rises nearer the water’s surface behind the jetty.

Hall pulled their fishing plan from his shirt pocket. He had developed an amazing detailed matrix that included moon stage, tide range, whether the river is rising or falling, mean river gauge at Venice, moon rise time, wind speed and direction and solunar table forecasts. Overlaying this were the periods of the day that the best bites occurred in previous similar trips.

I was intimidated.

But Miramon wasn’t.

“Rudy would like to engineer these fish,” he said. “It would take all the fun out of it.”

Then he cautioned about “the difficulty of duplication.” A great trip can be had one day, he said, followed by a poor trip the next day under what seem to be the exact same conditions.

Hall countered.

“I believe that we can duplicate some trips, but there are many variable conditions that we can’t recognize that also influence success,” he said. “But trying for duplication will improve your odds, even though you can’t be exact.”

Miramon went further.

“We will never understand the entire package about why fish bite,” he said. “Too much goes into it, even though we are always trying to get a better understanding.

“I’m not negative; I’m just a realist. It’s an imperfect art.”

Hall grinned hugely. He was enjoying himself.

“Nature makes the most elegant of designs, and duplicating them would be elegant,” he said. “It doesn’t always work, but it helps sometimes.”

After a pause, Miramon conceded.

“It absolutely helps,” he said.

Hall slipped in the last word.

“I fish with Chuck because he believes all my B.S.”

Silently watching the exchange and obviously enjoying himself was the third member of the fishing party, Miramon’s 21-year old son, Justin.

As the 24-foot Skeeter V-hull neared the end of its nearly 25-mile one-way run, tension built among the three anglers about what they would find at their destination. The ride was a little bumpy because of a south wind. Their fishing location was in the open Gulf of Mexico and directly exposed to south and southeast winds.

Miramon had been especially fretful. Hall coached him not to be so negative.

“I’m a realist,” he replied. “I’m not negative.”

As the boat descended the pass further, Hall commented that if it were too choppy maybe they could fish the beaches near the mud lumps. Miramon turned and smirked.

“He’s coming over to the realist side now,” he said.

As they entered the jettied area, all three men were relieved to find it calm enough to fish, and Hall pronounced the water to look “pretty good,” although by most standards of speckled trout fishing, it was putridly muddy.

The men watched the boat’s wheel wash carefully as they rounded the end of the jetty and moved along its back side. They were looking to see if the boat’s propeller turned up clear salty water from beneath the surface layer of muddy fresh water.

“You can’t discount the water here,” Hall explained “We will be fishing about 8 feet deep, and the water can be clear down there.”

The water in the wheel-wash was as muddy as the rest of the water, but the men were undaunted. Miramon stopped the boat to watch the current patterns before picking a spot and directing his son to drop the anchor.

Heaving swells rolled in from offshore and smashed over the barely submerged concrete wall of the jetty and into the river waters coming down the pass. Hall said that the trout lie down low and very close along the outside of the wall waiting for baitfish to come down the river pass and wash over it.

They began fishing at 5:30 pm. Hall rigged with a live shrimp under a sliding cork set for 8 feet deep. Miramon put a live cocaho minnow on a Carolina rig. The weight was so tiny that he was almost free-lining. The younger Miramon threw a Deadly Dudley Straight Tail in blue moon with a chartreuse tail.

First Justin Miramon then Hall hooked up on redfish. As the men unhooked and boxed the redfish to share with friends, the elder Miramon looked on.

“Redfish don’t interest me,” he said with obvious disdain.

For these guys, speckled trout are the Cadillac of fish.

“It is much more challenging to catch big trout than big redfish,” Miramon said. “If you catch a 30-pound redfish, that doesn’t mean anything. It just means you are in a school of big redfish.”

After the anglers boated a couple of more redfish, Hall picked up a decent 2 1/2-pound trout on a Deadly Dudley Straight Tail.

“We need to be in at least 2- to 4-pound trout in order to catch big ones,” he said. “If the number of fish caught is plotted on paper, it will form a bell-shaped curve. If the peak numbers of the curve are in that size range, the numbers of big fish in the curve will be a lot higher than if the peak of the curve is in the 1- to 2-pound range.”

It made sense.

The trout bite was slow. Only about every fifth fish was a speckled trout. The rest were redfish, mostly 25 to 28 inches long. After keeping a dozen or so for their friends, they pitched the rest back overboard as nuisances.

The men moved the boat up and down the extent of the jetty, sometimes anchoring and sometimes riding on the trolling motor. The water farther down the jetty was clearer, but the fish seemed more willing to bite near the end of the jetty.

Slowly, the trout came on board. Most were in the desired range, but no really big fish had appeared yet.

As the sun began to slip below the horizon, the water was still snorting out of the pass and the wind hadn’t abated, but they were determined to fish into the night. Carefully, they unpacked two large sodium-vapor lights and mounted them on the gunnels of the boat.

Sodium-vapor lights are used, they explained, because in their experience they have caught more trout under their yellow tint than under the hot silver glare of mercury-vapor lights.

At dark, they kicked on their ultra-quiet Honda electrical generator, and immediately large numbers of silverside minnows were attracted to the glare. They quickly dipped some of these to add to their live-bait arsenal.

The men fished unrelentingly. They caught great gobs of redfish and a smattering of trout, mostly of respectable, but certainly not trophy, size. Miramon explained their perseverance by talking about the trip that they made last year when he won the CCA STAR boat.

“We fished hard for several hours with blue moon Deadly Dudley Straight Tails with almost nothing going on,” he said. “We had only four fish, all around 3 pounds when I hooked the 7.2-pounder. The average guy would have left before that, but we stayed the course because we knew there were big fish in the area. After we caught that fish, we stayed and fished hours more, but only ended up with six trout. But one of them won the tournament. We were catching plenty of redfish that day too, just like today.”

Working off of Hall’s matrix, the men were looking forward to the 11:40 p.m. moonrise, which was when the bite was best on the trip this one was modeled after. When the moon rose, as the men hoped, the number of trout caught increased, but still that elusive 6-pound-plus fish evaded them. Finally, at 2 a.m., with a decent box of fish but no trophies, they decided to hang it up.

While taking a break before picking up their lights and stowing the rest of their equipment, Hall and Miramon talked about where they fish.

“What we call Venice is a vast area, and we love to fish it,” said Miramon, “but we fish all kinds of areas in and out of the Venice area.”

The two men ticked off the list: the Breton Sound platforms, Breton and Gossier islands, outside Breton Island, the beaches, jetties and platforms of East Bay, the roseau canes and their stubble in Blind Bay, the Block 69 rigs, the waters around the Chandeleur Islands and near Freemason Island. Occasionally, they will also fish in Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Borgne and the Biloxi Marsh.

Hall narrowed the discussion to fishing the South Pass jetty.

“This place isn’t for everyone,” he said. “In our circle of 25 or so other fishermen, there are only two others besides us willing to do this. It’s a 25-mile run one way to fish here.”

Miramon piped in.

“To add to the long run, the weather is a huge challenge,” he said. “We have made the run out here and had the wind come up, and we spent the whole night in the protected waters of the Coast Guard Cut without ever making a cast. And we never got to sleep either.”

Catching outsized trout is seldom easy.

“The South Pass Jetty is harder to fish than people think,” Hall said. “You have to be willing to lose tremendous amounts of tackle to the rocks here. You are constantly retying.

“Fishing here demands persistence. You will spend hours with no action sometimes. You have to be really interested in big fish and be willing to waste a lot of time to fish here. Plus fishing here demands an especially light touch. The bite is very subtle.”