The Atchafalaya usually gets to its lowest point this month, which means the water in the Basin is clear and its bass are stacked up.

The Choctaws called it “Atchafalaya” (ha-cha-fa-lia) for Long River, and, indeed it is long, winding through the center of a 930-square-mile region of bottomland hardwoods, with pristine backwater lakes, bayous and seemingly endless tupelo and cypress swamps in between. Its 595,000 acres make it the largest wetland river delta in the United States.

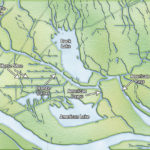

From Cow Island, Lost and Henderson lakes in the north near Butte La Rose at I-10 to American, Duck and Flat lakes in the south touching Highway 70, the Atchafalaya Basin’s waters flow through veins of bayous within its boundaries.

Year in and year out, in every season, there’s never a day that goes by where commercial or recreational fishermen aren’t running somewhere utilizing and enjoying the bounty the Basin provides — it gives freely to all. What’s more, perhaps one of the best times of the year to be in the Basin is fall, when the river’s down and the weather is starting to turn cooler.

Houma resident Matt McCorkel frequently fishes the Atachafalaya Basin, via its southern gateway at Morgan City. The young 33-year-old angler admits to specializing in bass mostly, but always looks forward to fall fishing, regardless of what he catches.

“Fall is a transitional period, and there’s a lot of different ways to fish this time of year,” said McCorkel, whose experience as a bass angler has served him well during his six-year tenure as an assistant manager at Academy Sports and Outdoors in Houma. “You can go out and throw crankbaits, and there’s fish that will hit on a crankbait bite. There’s going to be fish had on a topwater bite. There’ll be shallow-water fish, where flipping and punching grass is a technique that will produce catches.”

McCorkel admits that other times of the year in the Basin can be productive, such as the summer, but mentions it hinges on being there early or late in order to increase the chances of catching. Moreover, summer gets to be sort of a grind, where fall is more enjoyable.

“What makes it a transitional period besides the river really dropping is the water is cooling off and you’re going to have those fish on multiple patterns,” he said. “And it’s probably some of the most fun fishing outside of springtime. With the water lower and cooling, there are numerous patterns you can go out and try.”

Each spring, the river rises in the Basin and, more often than not, typically reaches levels above flood stage. For Morgan City, flood stage is 4 feet. For the Bayou Sorrel locks, it’s 12 feet and above Butte La Rose, it’s 25 feet.

As the water drops throughout the summer months going into the fall transitional period and depending on rain events and heavy southerly winds, water level in the Basin near Morgan City is around the 3 1/2-foot range. Therefore, fishing improves for every target species such as bass, sac-a-lait, bream and goggleye that recreational anglers go after during this period.

“Anytime you have falling water, it positions fish on more primary points than anything else,” McCorkel said. “They’ll congregate on a point nearest to deep water.

“I’m always trying to find places in the Basin with little points and breaks where fish will stage and set up. When the water is higher, they’ll be pushed up into the swamps, where access is going to be limited. When water is falling, it pulls the bait out — fish chase the bait. Generally speaking, they’ll be more on the outside edges of cover, and a little more accessible.”

McCorkel and I fished American Lake, parts of American Pass, the Orange Barrel Canal and the north end of Flat Lake in the Basin on a recent trip. Along American Pass, the noticeably stained high-water marks could still be seen on the trees providing us with some indication of how much the water had dropped since its peak in early summer, but also its lingering flirtation with flood stage into August.

Tossing crankbaits in the pass just off the bank in 3½ feet of water, McCorkle and I fished one of his favorite spots. At the base of some cypress and tupelo trees, on the outer edge of the grass, is where he picked up the first bass of the morning.

“Crankbaits when fished correctly can be more weedless than people think,” said McCorkel, whose pinpoint pitching accuracy with a variety of baits makes it easy for him to say.

When we did snag a couple times with the crankbaits, as everyone will at some point, a couple heavy-duty yanks shot the baits back toward the boat.

“I always tell people, fishing is a full-contact sport,” McCorkel said. “When I come back, I always come back with some kind of knick, scratch or bruise. But, seriously, you always want to feel your bait sinking and become a line-watcher too, because sometimes your line will stop or jerk, and there’s a fish on it. Basically, you want to maintain contact with the line throughout the pitch.”

There’s no doubt bass anglers — novice and seasoned — have multitudes of spinnerbaits of various colors in their tackle boxes. The spinnerbait has a reputation of being the go-to lure when starting a day looking for fish, trying to get a reactionary bite to establish a pattern.

Fishing spinnerbaits in the fall is still a productive method for fishing bass, but McCorkel suggests changing up a bit and downsizing.

“As the water gets colder, the bait is not as large,” McCorkel said. “The bream, they’re smaller; smaller shiners, smaller minnows, that holds true for the fall pattern. The later in the year you go, the smaller you want to go.

“If you throw a ½-ounce spinnerbait, try throwing a ¼-ounce. Some people will start throwing a bantam, 1/8-ounce bait. In the fall it’s still using some of the same techniques you used throughout the spring. I just highly recommend smaller patterns.”

Interestingly enough, there seems to be a biological reason for downsizing in the fall that matches what’s happening with bream in the cooler water.

Mike Walker is a biologist for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, who regularly works the Atachafalaya Basin. Walker, who also does quite a bit of fish sampling in the Basin, mentions that the last bream spawn is in late summer just before the water temperature cools down.

“It’s not uncommon for bream to spawn three times and maybe that last spawn has taken place at the end of summer,” Walker said. “Because their spawning temperature is much higher than bass or crappie, when that water temperature is dropping, they scatter out somewhat.

“When we’re catching them, there’s usually some kind of spawn going on, and they’re concentrated in an area like Flat Lake or wherever in the spring, and it could just be they are scattered out because the bass are getting more active and they scatter them — because they are going to be eating the little ones.”

While fishing the Top-6 in Toledo bend one year, McCorkle fished close to another angler who happened to see him and said, “Hey! I know you. You’re the Academy guy.”

Knowing baits, preferred colors, how to rig and marine equipment in general has helped McCorkel relate to his customers at Academy. McCorkel says it has allowed him to meet a variety of people and learn a number of places to go catch bass.

One technique that requires both patience and a great deal of finesse, along with the ability to read the edges and cover, is punching grass. McCorkel used this tactic extensively along with his acumen for finding fish in the Orange Barrel Canal, where we landed several bass and a couple of large bonus goggleye.

“Punching is a finesse technique using the ultimate power rig,” McCorkel explained as he sank his heavy jig through lilies and grass on the edge of a short bend along the bank. “You’re taking a ¾-ounce or 1-ounce or even 1 1/2-ounce weight with a heavy wire hook — trying to be as stealthy as possible, slipping it through heavy grass, water lilies and what not. The bass will get underneath those lilies any time there’s extremely hot weather, where they’ll use it for shade. During the winter, it’s also successful, when fish use these locations for warmth as well.”

McCorkel points out that punching grass is a methodical technique requiring patience, but it also requires stout tackle. The angler suggested 25-pound-test fluorocarbon or heavy braided line, along with 4/0 and 5/0 hooks and a minimum of 3/4-ounce weight.