Big burly redfish roam the deep reaches of the Southwest Louisiana marsh this time of year.

The captain pointed toward a slight undulation on the surface.“Eleven o’clock,” Chuck Uzzle said. “Do you see it?”

Low light conditions and not knowing what to look for had my eyes combing in all directions. This was not your normal “cast your topwaters as far as you can see” fish trip. I was a rookie, and was not playing well enough to stay in the big leagues.

“Right there, off the point — make a cast!” he exclaimed.

I hurled my hand-painted pink She Dog toward the placid shore, twitched it a couple of times, then watched it disappear. There was not a huge commotion like you would expect from a surface blow; rather, the fish seemed to open its jaws and slurp the plug, characteristic of a sow trout or snook. It could be the former, but no way it was the latter, especially in the Southwest Louisiana marsh.

Yards of Power Pro began peeling from my baitcaster. The braided line reverberated through my forearms with every brawny head shake the brute made.

“Big ol’ redfish,” Uzzle said.

The blaze orange bully identified itself as it made a run to the left into a ray of sunlight penetrating the water. Then it disappeared again, this time in a thick clump of marsh moss and grass. The pressure I was applying suddenly went limp.

I reeled down to try to tighten the slack, but all that came back was Power Pro. The microfilament had not failed me; rather, the knot-tier — me — failed to properly join the line with the 2-foot fluorocarbon leader, a move definitely warranting a demotion to the minors, at least in Uzzle’s eyes.

“That was a big one,” he said. “Let’s go find us another one.”

I was embarrassed; however, there would be many more opportunities for redemption before this day was over.

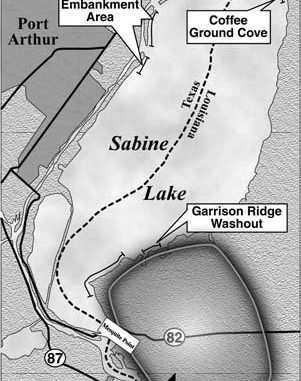

As the day matured and the sun began to climb in the Sabine Lake marsh, redfish appeared in every direction. A group to my left, right, front and aft kept me in limbo as to which direction to cast. A mental flip of a coin made gave me guidance, though there was never really a wrong side to the flip.

Redfish bit topwaters, soft plastics and flies all day. Most were oversized, in the 30- to 34-inch range, and well over double-digits on the Boga. All were the color of the most beautiful sunset you could imagine — a product of their brackish environment.

Fours hours after that first cast, I noticed something bright below the surface of the translucent waters. Uzzle poled the boat another 50 yards and retrieved my pink She Dog I had given to the first fish of the morning. The plug was lodged in the grass, a good 500 yards from the point it was eaten. I loop-knotted it to my line and made another cast.

Do You See What I See?

The signs may not be obvious to most anglers, but to the trained eye, redfish can be spotted from afar. Louisiana anglers rarely consider sight-casting to cruising redfish; however, it can be done, especially in the far reaches of the marsh where water clarity is excellent.

Some days, depending on the level of water, redfish actually show a part of their body above the surface. It may be a turquoise tail catching a ray of sunlight, or an exposed back as the fish roots in the shallows for small crabs or mud minnows. Regardless, seeing a redfish and casting a bait to it ranks up there with rattling up an autumn buck or high-balling a wary greenhead into the dekes.

“I’ll look for parts of fish on calm days,” said Uzzle. “If they don’t show themselves, I’ll look for nervous water or wakes on the surface. In 2 feet of water, if a wake suddenly appears it is almost certain that a big redfish is beneath it.”

Uzzle points out that many anglers cast behind the fish if they throw on top of the wake.

“It’s like pass-shooting ducks and geese. You have to lead them; get your gun barrel out in front of the bird. The same holds true when casting to cruising fish. Throw at least 2 to 3 feet in front of the redfish, and let it intercept it. It’s kind of like a good quarterback leading his receiver with a pass.”

Water levels in the marsh dictate where fish will stage; however, the inflow of incoming and outgoing tidal water is not a huge factor in prompting fish to feed.

“You really do not have to look at the tide tables to figure out when and where to fish,” said Uzzle. “I can look at the level of water at the dock and tell where the fish will be concentrated.”

It takes much longer for the water coming through the passes to reach the deep locales of the marsh. The correction factor on the tide tables may be as much as eight hours different in some stretches of Louisiana.

“Sight-fishing is not as much dictated by the tide because you are actually seeing the fish and not hoping they are where they are supposed to be; however, when tides are high, the fish are harder to find and scattered throughout the marsh. Low tides concentrate the fish in the deeper holes and make them easier to locate,” said Uzzle.

Change of Tactics

As every angler knows, perfect conditions are the exception and not the norm. On windy days, Uzzle said sight-casting to reds becomes much more difficult. The tell-tale signs of redfish are tougher to spot when rough surface conditions persist.

“If the wind is blowing hard, we may drift and blind-cast to cover more water,” he said. “We will make long casts using topwaters or spinnerbaits until we hit a fish. It’s not my favorite way to fish. I would much rather see them and cast to them; however, you can’t change the weather on certain days, and have to play the hand you are dealt.”

Uzzle has begun experimenting with chumming in the marsh. He takes a block of frozen shad and crab carcasses, grinds them up, freezes the mess, then puts it in a burlap bag to take into the area he will fish the next day. The idea is to get a concentration of fish in a small area, then work on them with defined drifts.

“You see those guys in Florida take the end of a baseball bat and fill it with bait fish then throw it out and chum the fish to the surface,” said Uzzle. “We are trying to do the same thing — draw a bunch of fish to a small area.

Getting There

Traditional center-consoled, deep-veed boats take you to the canals and bayous leading to the marsh flats, but do not float in the skinny water. If you want to sight-cast in the shallows, you need a boat to do just that — get shallow.

Uzzle’s 17-foot Maverick HPX Tunnel, in his view, is the “creme de la creme” of flats boats. Its quiet contour reduces hull slap and gets you closer to fish before they spook.

“I really have had to adjust to this boat,” Uzzle said. “Before, my old boat would alert fish much sooner due to the noise it created. Now, I am floating right up to fish and casting to them not 10 feet from the boat. These fish are so close it is scary at times.”

Uzzle said aluminum boats and other fiberglass models with elevated platforms will work, too; however, just be aware of the noise and vibrations they create, and adjust your fishing accordingly.

“You can be as quiet as you can, and these redfish still cruise off because they feel the vibration of the boat,” Uzzle said. “My Maverick is so quiet I get too close to the fish sometimes.”

Poling is the stealthy way to get up close and personal with these copper-plated brutes. Uzzle utilizes a Stiffy carbon push-pole that gets him from point to point. Models range from $300 to $1,000.

“Your push-pole is your trolling motor,” said Uzzle. “Look at the cost that way. It is difficult to catch fish in the shallow waters of the marsh on a trolling motor. If you go in buzzing, you will wake up every fish in the marsh.”

Importance of the Marsh

The hallmark of the Pelican State’s entire coastline is the extensive marsh and wetlands. Not by coincidence, these estuaries are prime fishing venues where anglers hook a plethora of specks, reds and flatfish.

Back when my youthful outdoor world narrow-mindedly revolved around waterfowl season, I only acknowledged the marsh as a winter home for me and millions of migratory ducks and geese. As I have grown older and my fishing prowess has too, I appreciate the role the marsh plays in our entire coastal ecosystem.

One of the most important benefits the marsh provides is a haven for juvenile finfish and shellfish. Biologists call it a nursery for its propensity to rear young crabs, shrimp and other organisms.

“The habitat makes the marsh,” said Heather Finley, Louisiana’s marine fisheries habitat program manager. “The marsh’s nice grassy cover provides an area where juvenile fish and shrimp can hide from predators.”

The organic matter from the marsh is pumped into the bays and helps sustain life to the lowest of the food chain. Marshes are critical to the productivity of finfish and shellfish. They provide a shelter due to their shallow waters and reduced salinity. Algae, little shrimp and smaller fish can feed on the organisms.

Brown shrimp use the marsh in early spring and white shrimp use it in late summer and early fall. Brown shrimp prefer a saltier environment, while “whities” can tolerate a fresher one.

Each square yard of the marsh holds an estimated 800 shrimp, and four times more young fish and crabs live in a marsh than in a typical bay.

The marsh consumes organic matter from nearby rivers and hosts decomposing vegetation throughout the year. When tides rise, like ardent spring tides or storm surges caused by tropical storms, the organic matter is dumped into the open bays, thereby fertilizing them with organisms that feed the bottom of the food chain.

Finley said Louisiana loses 25 square miles of marsh per year.

“When we lose marsh, we lose valuable physical structures that protect towns and break storm surges,” said Finley

Not to mention redfish.

Capt. Chuck Uzzle can be reached at (409) 697-6111 or cuzzle@pnx.com, or by logging onto chucksguideservice.net.