Current data may signal future changes in creel and size limits for fishermen in the Sportsman’s Paradise.

An inadvertent leak by a member of Louisiana’s Wildlife and Fisheries Commission has made public data that showed serious problems with statewide estimates of spawning stock biomass, spawning potential ratio and fishing mortality of Louisiana’s official state saltwater fish: the speckled trout.

“We sent these out to the Commission members as a tentative agenda item before the March meeting,” said Patrick Banks, assistant secretary of fisheries with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. “We knew the stock assessment showed overharvest, and we were trying to make sure we informed them as early as we could.”

According to Banks, the agency yanked the planned presentation of these figures to the Commission before its March 7 meeting due to errors found in the data.

“As we were checking numbers, we found mistakes in our preliminary analysis,” he said. “We had to rerun the model without the errors. The numbers changed in stock assessment, but they continue to demonstrate we have exceeded our thresholds.

“We are just not seeing biomass increase, and fishing mortality continues to be above limits of concern,” Banks said. “Our bottom line did not change.”

LDWF planned to send the revised analysis to other biologists in Gulf Coast states — Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas — for peer review during the week beginning May 20.

“I’m expecting it will take four to five weeks to get their comments,” Banks said. “I am not anticipating major feedback, and I hope that two weeks after we receive these comments — we will be at a point to bring this to the Commission officially.”

Banks said the agency will present the review to the public by late summer or early fall.

“We then hope to get from the Commission the kinds of regulatory changes they prefer: possible changes in creel limits, length limits, size limits or a combination of slot and creel limits,” he said. “It’s a matter of deciding which one or set of changes that offer the best bang for the buck in getting the stocks up again.”

Once the Commission decides which steps to take, they will be presented at statewide public hearings to receive comment from fishermen. The changes could go into effect sometime in 2020.

Preliminary figures

In order to interpret the following figures, it is important to understand that it is a preliminary analysis and numbers have changed due to the errors.

In order to interpret the following figures, it is important to understand that it is a preliminary analysis and numbers have changed due to the errors.

“I won’t comment on how much, especially since these will be out for peer review,” said Harry Blanchet, a fisheries biologist administrator for LDWF. “Some of the trends we’re seeing are in the same direction, but the scales may change.

“We are using maximum sustainable yield (MSY) in order to maximize the yield — as much harvest as we can not to affect recruitment.”

Recruitment is usually defined as the number of young speckled trout surviving to enter the adult stage and/or the fishery.

In Figure 1, SBB refers to spawning stock biomass: the combined weight of all speckled trout in Louisiana waters that are capable of reproducing.

LDWF estimates that the number of reproducing trout has dropped steeply since 2013 to approximately 3 million pounds in 2019. Trout SSB was as high as an estimated 11 million pounds in the 2000.

Blanchard would not comment on the target (yellow) line or the limit (red) line on the figure, other than to say that the limit line refers to the lowest SSB observed in 1989.

“The target is set above what we consider to be a comfortable distance that SSB is unlikely to get below,” he said. “This is based on variance . . . on a philosophy where according to the graphic (the limit) is the 5.7 million pounds of spawning female trout in 1989.”

In Figure 2, SPR refers to spawning potential ratio: a percentage representing an estimate of the stock’s potential to spawn with fishing pressure compared to spawning without fishing pressure.

After years of studying the population of speckled trout in Louisiana waters, a conservation standard of 18% SPR has been traditionally set.

In an MSY model, anglers can harvest trout at or above the conservation standard. Many other states manage trout populations and fishing pressure at an optimal yield (OY) standard set at 10% to 15% above their conservation standard, providing a margin of safety against significant increases in fishing pressure.

According to the figure, the current SPR is at 5% for 2018, 13 percentage points below the 18% conservation standard. The 5% SPR may be too low, but Blanchet would not commit to offering the revised data.

Regarding the target and limit lines, it is unclear whether this scale represents a new range of SPRs that spawning trout populations would fall in before new management decisions are warranted. Blanchet had no comment on that speculation.

The new SPR percentage range may also reflect a change in the state’s philosophy moving forward to manage Louisiana’s speckled trout as chiefly a recreational gamefish species, apart from the commercial/recreational model of the past.

Figure 3 looks at recreational and commercial landings of speckled trout over the years. In 2018, recreational anglers landed an estimated 3 million pounds of trout, 5 million pounds below 2012 levels.

Commercial landings for speckled trout continue but are limited to approximately a dozen remaining rod-and-reel, commercial anglers who were grand-fathered into the 1997 law designating Louisiana’s speckled trout chiefly a gamefish species.

Fishing pressure — and mortality — have continued to rise significantly, as indicated in Figure 4. This dramatic increase has persisted despite the drop in recreational landings illustrated in Figure 3.

Taken together, the increase in fishing pressure and decline in recreational landings may give credence to seasoned anglers’ reports of limited success in catching numbers of speckled trout and fish of quality in the Lake Pontchartrain basin, the Venice area and the Calcasieu estuary. Such reports have increased over the past five years.

Taken together, the increase in fishing pressure and decline in recreational landings may give credence to seasoned anglers’ reports of limited success in catching numbers of speckled trout and fish of quality in the Lake Pontchartrain basin, the Venice area and the Calcasieu estuary. Such reports have increased over the past five years.

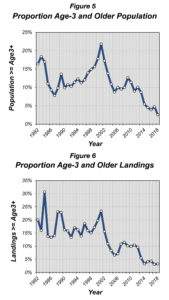

Figure 5 illustrates that the proportion of older speckled trout in the population is at the lowest level ever recorded. These numbers are derived from data sets gathered by samples taken twice a month by gill nets in five coastal areas: the Pontchartrain basin; the Barataria basin; the Terrebonne/Timbalier basins; the Vermilion/Teche/Atchafalaya basins; and the Mermentau/Calcasieu/Sabine basins.

In 2001, statistics suggest that the proportion of trout 3 years old or better was at a high of an estimated 22%, compared to approximately 3% in 2018.

This same pattern exists in harvest data from anglers obtained by the old MRIP and LA Creel, where the same 3% proportion was recorded for 2018, down from a high of 31% in 1984.

The proportion of older age-classes of trout are very important to researchers as low percentages often signal high fishing pressure. Also, older female trout may drop 10 times more eggs than younger females.

It is noted that speckled trout spawn several times between April and August. The presence of older, female trout is important to recruitment, and managing for higher numbers of older fish may help increase stock numbers in the ecosystem.

Since speckled trout spawn multiple times during the same season, they are very resilient to short-term flooding events that affect spawning success, but more research is needed to study the impact of long-term freshwater flooding events.

Since speckled trout spawn multiple times during the same season, they are very resilient to short-term flooding events that affect spawning success, but more research is needed to study the impact of long-term freshwater flooding events.

It’s remarkable that numbers of speckled making it into adulthood have been consistent from 1983 to 2018 as Figure 7 suggests. Speckled trout are a resilient species, and even the current drop in biomass and %SPR do not signal anything close to “threatened” or “endangered” status in Louisiana waters.

Trout appear to be an estuary-specific species, non-migratory, as tagging and acoustic telemetry studies in Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, Alabama and Texas have indicated. They are born, live and wander around the same waters and make surf runs outside, but close to the same estuaries where they were taken and tagged. Very few tagged trout show up in neighboring estuaries. One extremely rare exception was noted; one tagged fish was caught near Grand Isle after having been initially tagged in Florida, some 315 miles away.

These findings argue against a “tiderunner” theory for speckled trout, which suggests that trout populate inland lakes, bays and marshes from populations living in the Gulf of Mexico.

It is difficult to interpret Figure 8, although it appears to suggest speckled trout have been overfished since 2012. Again, revised data may suggest that the vertical red line may move right or left either, increasing years of overfishing or eliminating some years.

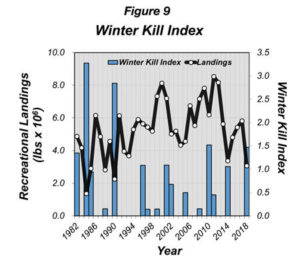

LDWF biologists also presented an experimental winter-kill index covering the years 1982 to 2018.

“Joe West took a look at some research from other states that reported winter kill,” Blanchet said. “We used that to come up with a ‘surrogate’ . . . not an ecosystem assessment.

“Joe West took a look at some research from other states that reported winter kill,” Blanchet said. “We used that to come up with a ‘surrogate’ . . . not an ecosystem assessment.

“And it’s on a sensitivity run . . . something to look at adding a parameter to consider the effects of hard winters on speckled trout.

“We also sent this index out for review to members of the Gulf of Mexico Fisheries Management Council,” he said.

Changes coming for anglers?

Due to the high fishing mortality and reduced stocks in the recent assessment, anglers will see changes in trout regulations since the trends have remained the same, even with a corrected, revised analysis, according to Banks.

Speckled trout are managed in south-central and southeastern Louisiana with a 25-fish daily creel limit and a 12-inch size minimum. In western Louisiana — the Mermentau/Calcasieu/Sabine basins — anglers may keep only 15 trout daily, with a 12-inch size minimum and no more than two fish per day longer than 25 inches. That regulation was implemented to try and retain large speckled trout and create quality trout fisheries in Calcasieu and Sabine lakes.

All other Gulf Coast states offer more-conservative harvest restrictions and standards. It must be understood, however, that Louisiana encompasses more habitat for speckled trout than other states, possibly enhancing rapid stock recovery.

Size limits are often used by fisheries managers to protect recruitment. A 12-inch minimum size protects speckled trout long enough that they have at least one spawning season before they are legal to harvest. Size limits could be extended to allow trout to spawn in successive years.

Slot restrictions, on the other hand, are also often used in conjunction with creel and length limits to try and grow more adult trout into quality status and increase spawning opportunities, while limiting numbers of adults harvested above the slot. Slot restrictions can also be utilized to target year-classes of speckled trout within slot ranges.

What will Louisiana anglers face in 2020?

Neither Banks, nor Blanchet did not provide any hints about future creel, length or slot restrictions, other than Banks saying that recommendations will be presented to the LWF Commission this fall.

“We will make these recommendations to the commission based on science,” Banks said. “We will then consider public comment and eventually move forward with changes.”

About the possibility of LDWF recommending different regulations on a basin-by-basin or zone-by-zone basis, both said it was too early to know.

“Five years from now, when we have a good history with collecting this data through LA Creel, then we’ll be able to do that,” Blanchet said.

Any upcoming changes will likely be mandated on a statewide basis, or with different regulations set for the western part of the state.

Is the grass always greener on other side of the fence?

Here are regulations with which other Gulf Coast states manage speckled trout.

Florida

Zone-by-zone restrictions.

Northwest Zone (Escambia County through Fred Howard Park Causeway near Pasco County), five fish daily, with a 15- to 20-inch slot limit and one fish daily more 20 inches or longer. From May 11, 2019 through May 31, 2020, all speckled trout caught must be released in waters between the Pasco County-Hernando County line and Gordon Pass in Collier County.

Northeast Zone (Flagler through Nassau counties): six fish daily, with a 15- to 20-inch slot limit, with one fish daily 20 inches or more.

Southeast Zone (Miami-Dade County at Card South through Volusia County) and Southwest Zone (Fred Howard Park Causeway through Monroe County line at Card Sound): four fish daily with a 15- to 20-inch slot limit, with one fish daily 20 inches or larger. From May 11, 2019, to May 31, 2020, all speckled trout caught must be released in waters from the Pasco-Hernando county line through Gordon Pass in Collier County.

Alabama

Effective Aug. 1, six fish daily, with a 15- to 22-inch slot limit. Only one fish over 22 inches may be kept.

Mississippi

A 15-fish daily limit and 15-inch size limit was adopted in 2017.

Louisiana

A 25-fish daily creel limit and 12-inch size minimum except in specified areas of Cameron and Calcasieu parishes, where the daily creel limit is 15 fish with no more than two over 25 inches per day. The specified areas are: south of I-10 from the Texas-Louisiana boundary east to its junction with LA Highway 171, south to Highway 14, south to Holmwood, and then south on Highway 27 through Gibbstown south to LA Highway 82 at Creole and south on Highway 82 to Oak Grove, then due south to the western shore of the Mermentau River, following this shoreline south to the junction with the Gulf of Mexico, and then due south to the limit of the state territorial sea.

Texas

In waters north of FM 457 in Matagorda County, 10 trout per day. In waters south of FM 457, five trout per day. Fish must be in a 15- to 25-inch slot, with no more than one larger than 25 inches in the creel per day.

Effective Sept. 1, 2019, the five-fish creel limit and 15- to 25-inch slow limit will be coastwide, including the Texas side of Sabine Lake.