Sure it’s hot, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get in on some excellent wing-shooting.

As the hunter called excitedly, he could see the reaction from the birds when his notes hit them. They spotted the decoys and came in over the water as though the caller had them on a string, although he’d put his blind on the bank.

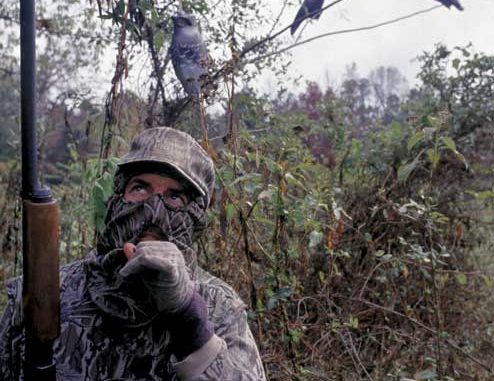

Even with the birds less than 40 yards away, they couldn’t spot the hunter dressed in full camouflage, including hat, headnet, gloves, shirt and pants. When he came up, he took aim on the lead bird and fired.

As two more birds flared, he swung quickly, fired twice and dropped one of them. Most of the birds landed on the water. His friend also had taken two.

When the birds flew out of range, both hunters sent their Labrador retrievers on their assigned missions to race out of the blind, spring like jackrabbits into the water, swim for the downed birds, pick them up and bring them back to the blind.

Once the dogs returned and dropped the birds in the blinds, one hunter looked at his partner, smiled and asked, “Isn’t this the finest duck hunt you’ve ever had?”

He laughed.

“This is great,” he said. “No one would believe you could shoot this many birds in one day in July and have this much duck-hunting fun out of duck season without poaching or breaking the law.”

Summertime duck hunting sounds illegal, and it is. However, if you simply change which bird you hunt, you’ll find all the other elements of duck hunting in place. These hunters shot crows, not ducks, over water.

Before you decide there’s not much effort involved in hunting crows, consider that crows have a complex communication system. Ornithologists have identified 50 different expressions crows make. For instance, the sounds “caw-aw, caw-aw, caw-aw” assure the flock of safety. The “kawk, kawk, kawk” sound warns crows of danger. Scientists have found that crows, like parrots, can learn to repeat words and long phrases. You’ll find crows with their high intelligence and keen eyesight hard to fool when you hunt them.

Clever crows

A question arose a couple of years ago in Hamburg and Berlin, Germany, concerning the findings of thousands of toad corpses around some ponds. Officials tested the ponds’ water quality to see if that could be the problem, but the results came back negative.

A local scientist suggested that hungry crows were pecking out the toads’ livers. The veterinarian assisting the investigators, who studied the toad corpses, said that the toads’ chest areas had been opened, and the livers removed, causing the toads’ lungs to puff up and pop.

Crows are extremely smart animals that tend to repeat the actions of other crows as they see them. Scientists conjecture that crows have mimicked what their leader crow does to get food and survive.

Crow hunting

Most states have designated their crow seasons to take place in the fall with specific beginnings and endings, with Louisiana’s crow season running Sept. 1-Jan. 1 with no limit. However, you can take crows year-round, except on WMAs, during legal shooting hours, as outlined in Louisiana’s other hunting season’s regulations that specify the allowance of crow hunting “if crows are depredating or about to depredate ornamentals or shade trees, agricultural crops, livestock, wildlife or when concentrated in such numbers that they cause a health hazard.”

In many areas of the South, crows create more crop damage than even ducks do in rice fields. Louisiana farmers harvested 17.7 million pounds of pecans in 2003, with a gross farm value of more than $15 million.

Crows will walk down corn fields and pick up every grain of corn in a row and strip a peanut field of peanuts the same way. But throughout the South, crows create the most crop damage in pecan fields. A large flock of crows can go in and destroy an entire pecan crop.

No one considers crows welcome visitors. The Agriculture Experimental Station for Pecan Research in Shreveport has tried to get a crow-control program started using a toxicant, which will cost $300-$400 per landowner. You can save the landowner that money by hunting his crows for him.

Crow tactics

Will Primos of Flora, Miss., president of Primos Wild Game Calls, has hunted crows for almost four decades. He enjoys setting up to call crows, and uses decoys to bring in the birds.

“I try to determine from which direction the crows will come in, and then I know how to set up,” he said. “Because crows usually like to fly into the wind, I want to make sure I have the wind at my back and be facing the direction from where the birds are coming.

“I’ll use crow decoys and an owl decoy to help lure in the birds. You can carry a dozen of these decoys wadded-up in the back of your hunting coat, and they don’t weigh anything. By setting up the decoys, you give the crows a visual picture of what they’re hearing.

“If I’m calling aggressively and trying to simulate a fight, I’ll use the owl decoy. If I’m not calling aggressively and am not attempting to get the crows really excited, then I won’t put out an owl decoy.”

To give the set-up a more realistic look, Primos takes rubber bands, black cloth and rocks into his stand site by the water.

When he spots a crow, he puts the rubber bands around the black cloth with the rocks inside and throws the rocks and cloth into the air. The rocks carry the cloth high into the air and cause it to fall back to the ground. When the crows see that black image diving to the ground, they assume the cloth is a crow diving in to fight the owl decoy.

“When I begin to call, I start by giving three or four ‘Hey, I’m over here. You guys come on over,’ types of calls,” Primos explains. “If I get the crows’ attention, I’ll give three or four shorter, louder and more-aggressive calls to simulate a fight. Then as the crows begin to come in, I’ll make longer calls.

“Often I’ll give six to eight calls in a series, which I call a riot call, which tells the crows, ‘Hey boys, I have an owl over here, and we need to whip him. You fellows come on right now and let’s pound on his head.’”

To successfully utilize Primos’ style of crow calling, you must stay 10 to 20 yards away from the decoys, since that’s where the crows will look, wear camouflage from head to toe and try to hide in some kind of cover close to the water to keep the crows with their very keen eyesight from spotting your silhouette.

Because crows often will fly in and circle to look over your set-up, Primos suggests you take the shot as soon as you find the birds in range and before they have a chance to see you. Once you shoot an area, Primos advises that you wait a couple of months before returning to the same spot and calling crows there again.

More tactics

Jerry Tomlin of Milledgeville, Ga., has developed a unique style of crow hunting that harvests numbers of birds. Tomlin also likes the decoy call-and-wait strategy.

But he says that often hunters overcall to crows.

“I depend more on my decoys than I do my calling to bring in crows,” he said. “I want to call just enough to get the crows’ attention and then have them come into the decoys.”

Tomlin has found crows travel certain flyways, similar to doves and waterfowl, and have specific types of crops on which they prefer to feed.

He loves hunting from now through the end of the year.

“Fall is a great time to hunt crows and continue training your Lab,” he said. “Not only are resident flocks of crows present, but also new crows are migrating in to where I live from the North ahead of the cold weather.

“Pecan orchards, which flourish in the South, seem to be the favorite food of crows. Crows do millions of dollars worth of damage to pecan orchards each year. I have landowners with pecan trees who call me each season and ask me to come in and take a bunch of their crows.

“Often, if you eliminate a farmer’s crow problems, he may open his lands to you for hunting other species of birds and game.”

Because of the crows’ keen eyesight, when Tomlin sets up, he wears full camouflage and has his blind fully camouflaged. Tomlin bases his crow-calling strategies on the premise that crows like to socialize.

“Aggressive calling will bring in numbers of crows for a short time,” Tomlin explains. “However, if you just use feeding and socializing calls and crow decoys, you can call in more crows to the same area for a longer time.”

In 17 hunts one season, Tomlin and his buddies rid pecan orchards and peanut fields of almost 900 crows by starting to shoot at sunrise and hunting until 11 a.m.

“Scouting is a key ingredient to successful crow hunting,” he said. “I spend a great deal of time trying to pick a place where I can find 100 to 200 crows congregated.”

Using his blind-and-decoy technique, Tomlin will have one, two or three crows coming in at a time rather than the 15 to 20 crows that will swarm in when he calls very aggressively.

“When you call aggressively and have a large group of crows swarm in to you, you and your friends only can bag three or four birds out of the flock,” he said. “Then you spook the rest of the crows, which makes calling in any more birds difficult.”

After Tomlin shoots an area, he waits about three or four weeks before he returns to that same region to shoot more crows, and finds that he can call the crows much easier then, than if he returns only a week later.

Although Tomlin concentrates most of his crow hunting around pecan orchards, peanut fields and corn fields, you need to also look at ponds on dairy farms and beef cattle farms where the animals eat corn. Freeloaders looking for free grain, peanuts or pecans anywhere they can find them, crows love these kinds of places.

“The University Extension Service in Georgia estimates one crow will consume 7 pounds of pecans per season,” he said. “When you have swarms of 200 to 400 crows in a pecan orchard at a time when the nuts are ready to fall, the crows can destroy the pecan crop.

“I had one grower tell me that because of crows he only harvested about 100 pounds of pecans out of his 40-acre orchard one year. Crows eat the pecans and also will peck holes in the ones they don’t eat, which spoils the meat of the pecans and makes the them unsuitable for commercial sales.”

Dog training

Hunting crows like you hunt waterfowl provides some tremendous opportunities for a retriever

If you’ve searched for a place to train your retriever on live birds without going to a preserve, consider summertime crow hunting over water where allowed. Probably few landowners will deny you permission to hunt crows over water. More than likely, conservation officers know enough landowners who will welcome you, your dog and your decoys to come and crow hunt their properties.

You can use decoys, set up blinds and use your retrieving dogs to go out into the water, pick up the crows and bring them back to you.

By hunting crows in the summer and early fall, you can give your retriever plenty of waterfowl-retrieving experience and retriever training without shooting ducks or having to wait until duck season arrives. You also can have a great time calling and shooting at a time of year when most hunters don’t get to hunt and shoot, especially waterfowlers.