While it requires some effort, experiencing turkey hunting success on small properties can be a reality if birds visit the property on a regular basis in response to good habitat management.

Opening day of the 2008 season, I was set-up in my ground blind on a wheat/clover patch I had planted with two sorghum strips during the spring of 2007. While the grain strips were not great due to poor growing conditions, the plants had produced some seed heads in addition to some native vegetation such as goat weed. I left the strips standing during the fall planting season, and in December bush-hogged them, and then in early February plowed them up. I had seen a few turkeys in the patch during the deer season, including a group of three jakes.

When I visited the patch in early March, I found good turkey sign, tracks, droppings and scratching, so I knew the birds were coming to it on a regular basis.

I let out a few tree yelps, and immediately had a hen respond. As it got to be fly-down time, I let out a series of yelps and cackles. The hen responded, but there was no gobbling.

A few minutes later, the hen sailed into the patch from the woods in front of me. It was a beautiful sight, but unfortunately would be the highlight of the day. After a few more hours of no gobbling and no other birds visiting the patch, I called it a day and headed home.

Three days later

Once again, daylight found me in the ground blind of the two-acre patch, but this time, the jakes were gobbling about a hundred yards north of me. Most hunters would probably have headed out closer to them for another set-up, but I knew the birds had been coming to the patch with the hens, so I decided to stay put.

I talked turkey with them for a while, and then shut-up and waited for them to come from the woods road to the west of me (my right).

After about 10 minutes of no activity, I yelped loudly again and waited. I heard the sound of heavy wings flying down in the pine plantation just east of me, and figured it was the hen returning to her patch.

I was looking to my right waiting for the jakes to appear when I heard the distinct sound of a drumming tom. I turned my head to the left as the longbeard stepped out of the pine plantation about 15 yards from me. The gobbler stayed in a full strut as it started moving slowly toward my two decoys.

I could not shoot out of the window, and had to wait until the tom was in front of me. I just sat and waited, hoping the gobbler would not figure out my set-up.

The gobbler never came out of it’strut as I eased my old 20-gauge up to my shoulder. This was my first gun, and I had never killed a turkey with it. I had put a scope on it for shooting slugs, and as the tom came into view, I placed the crosshairs on it and waited.

When the tom eased its neck and head away from the body, I fired. The gobbler fell over backwards and never moved. It was my first turkey with my first gun and the first turkey killed on this 60-acre tract since it was purchased 15 years ago.

I had hunted the tract every year, and had never even heard a turkey gobble anywhere near the property. I credit this tom to the turkey strips that I had incorporated into my planting program. Hopefully this will be a regular event.

Seasonal distribution of turkeys

Managing turkeys on small properties can be difficult due to the wandering nature of the birds. Turkeys are constantly moving about when feeding, and can cover several miles in a single day. Thus the landowner or manager with only a few hundred acres may have birds for only a few minutes before they are off the property. It is especially tough for the person with less than 100 acres. The time that I observed birds feeding in the patches was usually less than 30 minutes.

In the fall and winter, feeding is generally associated with the hard-mast crop. The river drains, streamside corridors and oak flats are generally the areas where turkeys can be found during the fall and winter months. If you had been seeing turkeys on your property in late summer and suddenly they disappear, chances are it is due to the mast crop, especially if you don’t have many hardwoods on your property.

In the spring and summer (the breeding, nesting and brood-raising time), the birds are back in the fields, pastures and small forest openings, where grasses, forbs and insects abound. Spring and summer is usually the time I see turkeys on the 60-acre and 25-acre tract, mainly due to their feeding habits. As the acorns begin to disappear in late winter and green-out approaches, the turkeys begin to show-up again.

Property evaluation

The first thing to do when deciding to try and improve your habitat for turkeys is to determine what turkey habitat you have and what turkey habitat is around you on the adjacent properties. Most people probably have a good idea of who their adjacent landowners are and what they’re doing for wildlife.

If, however, you don’t, get a good map of the region, or just drive around and take notes of what you see. Fred Kimmel, upland game biologist for LDWF, uses the term, “see what’s missing.” Then try to provide the missing link on your property.

If your property is surrounded by lots of pastures and fallow fields, then you probably do not need to develop openings for birds. However, if these fields are primarily summer hay fields, then a winter patch of grass and clover will provide some diversity in the landscape.

If you are surrounded by dominant pine timber and you have a good stand of oaks, then you probably want to manage your oak stand and not clear-cut or convert it to pine.

If you do have pine timber like everyone else, but they do not burn their woods, a prescribed burn on your property during the dormant season may just be the ticket.

Once you have made the evaluation, develop a management plan. Biologists with LDWF are always available to help landowners with wildlife management.

Management work on small tracts

Generally, the older stands of pine and hardwood are better for turkeys. Hardwood clear-cuts and young pine plantations do offer some nesting habitat for a few years, but turkeys will soon abandon these sites. Visibility is an important part of a turkey’s life in this dog-eat-dog world, and dense vegetation does not provide the visibility turkeys need in order to avoid predators.

Timber management should favor the hardwoods, both hard- and soft-mast producing species. Thinning of older stands will help create nesting habitat and promote vegetation growth of grasses, forbs and fruit-producing shrubs such as American beauty berry. If your habitat is lacking in hard- and soft-mast tree species, then planting desirable tree species in openings is an appropriate management activity.

Cutting dominant pine stands and allowing them to regenerate with hardwoods would be another method to increase the hardwood component on your land. Red mulberry is a very desirable soft-mast species to plant for turkeys and other wildlife. Sawtooth oaks are often promoted, and I have seen turkeys actually jump up into these trees and pick acorns off from the branches.

Prescribed burning is an important tool for managing middle-aged and older pine stands. The burning helps to control the understory vegetation, which can become too dense for turkeys, while promoting the growth of grasses and forbs, especially legume species.

Kimmel recommends a three- to five-year burning rotation program. Some landowners burn their woods every year to maintain good visibility, but it really eliminates good nesting habitat for the birds.

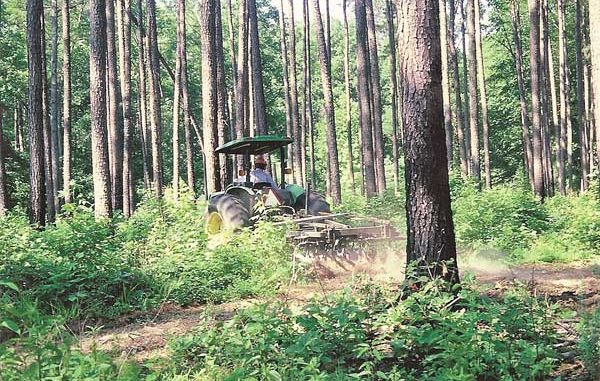

Additionally, a little tractor work to reduce the vegetation height and some soil disturbance is always good for birds that feed by scratching through the soil and ground cover in search of seeds and insects. Utility rights-of-way can be ideal areas for such management work.

Plantings are regularly promoted by wildlife managers, and this is probably the best tool for the small landowner. Clover is an excellent forage crop for turkeys, and can be easily combined with a winter grass into a nice food plot.

These patches should be allowed to “seed-out” in the spring for the birds.

Grain plantings are also a good management tool for turkeys. Most small landowners probably cannot plant a lot of corn, but plants such as sorghum, Egyptian wheat and millet can be planted in a patch or in strips, and will be used by the birds. Leave the patch or grain strips during the fall and winter, and then in late winter or early spring, cut and disk them.

Turkeys have strong legs and big feet for scratching the ground to uncover seeds, tubers and insects. One forage crop that is excellent for turkeys is chufa. Chufa is a sedge, and looks like a grass. It is planted in the summer, and produces tubers in the soil in late summer.

Turkeys and other wildlife species will dig the tubers in the fall, winter and early spring. The problem with chufa is that you cannot use the plot for a winter patch (otherwise, you have just wasted your time and money).

LDWF, the LSU Extension Service and the National Wild Turkey Federation all have information about managing habitat for wild turkeys. With a little work on your end, a small tract of land can provide habitat for turkeys and some spring hunting for you.