The Atchafalaya Basin doesn’t fit the stereotype for ideal turkey grounds, but the birds that flourish there haven’t seemed to notice.

Despite their adventurous nature, the English Puritans who settled in America in the early 1600s were not singly outdoors-oriented.

Today the term outdoors person suggests a fisherman or hunter, especially the latter wherein one has a working acquaintance with guns and some knowledge of game birds and animals.

Being totally unfamiliar with wild turkeys, the Pilgrims made a gross mistake by shooting, plucking and preparing to make a meal out of a bird that definitely was not the fowl of choice for future Thanksgiving feasts.

As the story goes, the emigrants noticed Indian inhabitants roasting and eating huge, dusky birds. Turkeys, of course.

Forthwith, the newcomers loaded their guns and went hunting, naively unaware of the difference in variety and table quality of big, dark-colored birds. The first ones they came upon looked kind of like those the Native Americans hunted and ate with gusto. So they shot, dressed, endured what must have been rank cooking odors and proceeded to eat their kill, which to their disgust turned out to be not turkeys but — oh my! — turkey buzzards.

Thus an inauspicious beginning of what is presently one of our most endeared annual events, Thanksgiving Day, observed by dining on turkey.

Turkey hunting has come a long way since the Pilgrims landed and established colonies on American shores — all the way to the Atchafalaya Swamp of all places.

Classic wild-turkey territory would seem to be the high and dry pine forests of, for example, Livingston, Feliciana, Tensas and some 40 other turkey-bearing parishes.

Terrain featuring a jambalaya of potholes, shallow inland lakes and buttonwood bogs much of the year is at odds with what is perceived as typical upland game-bird habitat. Ducks and woodcocks yes, but not turkeys.

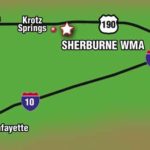

Yet it is so. Wild turkeys now populate the Atchafalaya Swamp in huntable numbers, particularly in the upper and middle sections, from Highway 190 in the north to its southern reaches below Belle River, 60-plus miles and nearly a million acres of variable forest including stands of shroud cypress trees, ideal turkey roosts, flanking the Atchafalaya River.

Introducing wild turkeys to the great swamp was jump-started several decades ago by farsighted members of the Lottie Hunting Club, who stocked and nurtured turkeys on their hunting range off Bayou Close at the tail end of the Morganza Spillway. The birds multiplied and inevitably wandered into the hinterlands south of Big and Little Alabama bayous, the des Ourses bottoms and beyond.

Tony Vidrine, state Department of Wildlife and Fisheries wildlife division manager of Region 6, has his finger on the pulse of turkey hunting in the Atchafalaya Swamp, radiating from Sherburne and Attakapas wildlife management areas. At Sherburne it is a vibrant pulse.

When LDWF obtained the tract of land along the east, bank of the Atchafalaya River, now Sherburne WMA, off Highway 190 near the town of Krotz Springs, the agency stocked it with turkeys and closed the season on them for five years, allowing the birds to take hold. When the area was opened to turkey hunting in 1995, an astounding 122 gobblers were bagged by hunters; last season, 92 were harvested.

The 10-year average is 50 turkeys per season, which runs nine days. The first five days are by lottery only; the final four days are open hunting by self check-in on site.

Obviously Sherburne, at 44,000 acres among the more extensive of the 60 state-run WMAs, is a highly productive public hunting ground, not only for turkeys but also deer and smaller game animals.

As yet there is no turkey season at Attakapas WMA in the lower basin. While some birds are sighted in the vicinity, LDWF field biologists have determined there aren’t enough to have a viable season. The numbers are growing, though, and the department is working toward opening the area to turkey hunting in the near future.

Complete rules and procedures relating to hunting gobblers at Sherburne and elsewhere in the state are listed in the department’s Turkey Hunting Regulations pamphlet.

In the broad view, great swaths of the Atchafalaya Swamp are leased to private hunting clubs with no public access.

Fortunately, in addition to the WMAs, the state has thousands of acres (some owned outright, others accessible courtesy of private estates and major corporations) in the basin open to public hunting of all legal game birds and animals. The black-and-white STATE LAND signs indicating open range in scattered parcels throughout the basin are welcome sights to sportsmen who have no place else to hunt.

The saga of wild turkeys in the state took a biblical path: Years of plenty followed by decades of depletion, then restoration.

A case in point, in the 1890s when rural Louisiana was undeveloped, biologists assisted by expert woodsmen estimated there were a million wild turkeys here. This abundance was celebrated perhaps with too much optimism shortly after the turn of the century when, in the first attempt to regulate turkey hunting, the limit was set at 25 gobblers a day! By all accounts, even that lavish limit was generally ignored.

About that time, large-scale logging was taking place, thinning out lofty trees where turkeys roost. That coupled with settlers clearing wilderness plots for farming and livestock ranching along with increased hunting pressure started a devastating decline in bird numbers.

In 1933, hunting turkeys was banned. By the 1940s, there were fewer than 2,000 in the combined turkey parishes.

In 1960, a turkey restoration program initiated by the state Department of Wildlife and Fisheries jumped into high gear, funded by federal and state revenues. Through a deal with the state of Florida, Louisiana acquired a number of birds in a deer-for-turkey swap.

The deer were captured on the Mississippi River savannahs below New Orleans in a 20th century-style deer drive. Rousted from willow and roseau thickets on the floating marsh by helicopters and pilots associated with the petroleum industry, the animals were rounded up by LDWF agents and civilian volunteers, tranquilized to ease the stress of being manhandled, and later shipped to Florida in a one deer for one turkey trade.

It’s romantic to presume the transplanted turkeys were Osceolas, named after the Seminole war chief, from the fabled Everglades rather than the more common Eastern strain. But no matter. Descendants of the transferred Florida gobblers took to the Atchafalaya Swamp cypress trees like gravy on rice.

Ultimately the proliferation of turkeys in the Atchafalaya Swamp may be the result of a natural occurrence, sedimentation.

Turning squashy earth into solid footing is a subtle process that takes years and involves regular doses of floodwater. The swamp has been gradually filling in due to silt deposits left by spring floods, occasionally in double digits, dispersed by the Atchafalaya River. Water comes in fast, goes out slow, leaving behind a new layer of filtered sediment each season. Large lakes in the middle basin 20 feet deep 50 years ago are now only 10 feet deep, expanding shorelines as they shrink in volume.

The long-range benefit of accreted landscape is spreading of fruit and kernel trees such as hackberry and oak, and fertile meadows of seed grasses that nourish deer, rabbits, squirrels and, of late, turkeys.

Unfortunately, the laws of physics must be accommodated: For every action there’s usually an opposing reaction. In this case, increased hunting acreage means decreased fishing domain.

Nevertheless, the end result of well-managed restoration projects and hands-on sportsmen participation is the statewide wild turkey flock holding steady at 90,000 birds, with almost that many hunters trying to bag a gobbler every spring.

Some 10,000 of us do.