Even the cagiest veteran turkey hunter can learn a lot from Northwest Louisiana’s Tommy Smith, who has more than 200 birds to his credit.

“You need to park a little way down the road and walk to the tram; you don’t want to drive in too close because you never know where one might be roosted.”

With these words of instruction from my host, Tommy Smith, I left the campgrounds at San Patricio south of Mansfield and parked my truck less than 100 yards down the road leading to the old tram, a long-ago abandoned railroad bed that ran adjacent to a creek bottom.

Wild turkeys were known to roost and feed along the tram, and I hurried along the sandy road, trying to outrun daylight which was rapidly approaching. A crow flew overhead, cawing loudly as I hurried along.

G-G-G-O-O-O-O-B-B-B-B-L-L-L-E-E — the roar of a longbeard turkey gobbler practically knocked my hat off as I skidded to a halt. The vocal bird that responded to the crow was roosted in a pine no more than 200 yards off the road, nowhere near the old tram.

I sneaked into the pines, placed a hen decoy in front and settled down against a tree. I softly yelped; the gobbler answered, and I heard his wingtips flicking branches as he flew down. When he stepped out from behind a clump of wild fern, he was 5 feet from my decoy. A load of No. 6s did the trick, and my hunt was over practically before it began.

Driving back to the San Patricio camp, I met my host, who congratulated me on my success.

“I’m glad you got that old sucker,” Smith said. “He’s probably seven or eight years old, and intimidates all the other gobblers in the area. Maybe they’ll start gobbling now that the big bully is gone.”

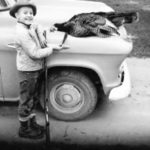

My bird was indeed a good one. With a beard measuring 12 inches and wide-based spurs just a tad under 1½ inches, the gobbler tipped the scales at 23 pounds.

I’d have never waylaid that gobbler nor the other three I took in the area in later years had it not been for the sound advice and tips offered by my host.

For several years, I have hunted turkeys as a guest of Smith on this property formerly owned by International Paper Company. Smith was and still is a wildlife biologist for these woods, which have since been purchased by Timberstar Southwest.

Over the years, I have sat and listened as Smith revealed details of some of his hunts. The thing that stuck in my mind has been the fact that more often than not, he has walked out of the woods with a longbeard gobbler swung over his shoulder.

I sat down with Smith recently and picked his brain, hoping that some of the turkey hunting expertise he has accumulated over the past 45 years of chasing gobblers might seep into my cranium, which has plenty of free space when it comes to having a grasp of how these majestic birds work.

Smith was reared in Dewitt, Ark., and grew up hunting turkeys with his dad, who learned how it was done from his father.

“My grandfather hunted turkeys in the 1920s when there were very few turkeys in Arkansas,” Smith said. “I started going out with my dad when I was seven or so years old. I shot at my first turkey when I was eight, and finally killed my first one on my 11th birthday.

“We were hunting on the land of a friend near the White River; he had given Dad and me permission to hunt there. We watched a gobbler fly up to roost one Friday afternoon, and were set up on him the next morning before daylight.

“I got to watch the gobbler fly down and break into strut, and Dad brought him in on a string with his old yelper. I shot him with Dad’s 12 gauge, and I’ve been hooked on the sport ever since.”

Smith heads for his home state several times each season to hunt with his dad, now 79, who still lives in Arkansas. What his dad taught him has served as the basis for a pool of turkey hunting knowledge he continues to add to each season.

“Back in the early days of hunting, camouflage clothing had not come on the market,” Smith said. “I hunted in blue jeans and wore an old olive drab coat and matching hat. Instead of sitting against a tree in full view of a turkey as hunters do today, we hid behind a log or stump.

“Dad’s favorite call was a Leon’s yelper, a little box with a diaphragm stretched across it. Later, Ben Rodgers Lee came out with a mouth call, and Dad got introduced to that. He learned how to stack the reeds, one on top of the other, to create the raspy sound he wanted. He taught me how to work the diaphragm, and I use it a lot today.”

Incidentally, the Leon’s yelper, according to Earl Mickel’s “Turkey Call Makers Past and Present” was awarded a patent in 1955. The call was invented by Leon C. Johenning of Lexington, Va., and was described as an “out-of-the-mouth box type diaphragm call.” No doubt, those calls in mint condition would command a high price by collectors today.

However, the call used by the elder Smith probably spent very little time on the shelf collecting value. It was more likely to be found collecting scratches and dings, and gobblers, in the turkey woods.

Smith’s turkey gun he uses today is a Remington Model 1187, 3-inch magnum, and his ammunition of choice might come as a bit of a surprise to most hunters who shoot 4s and 6s.

“I shoot No. 2 high brass shells mostly because that’s the shell my dad has always used,” Smith said. “I’ve found that it will kill a turkey dead, but if you happen to miss or make a bad shot and he flies or runs, these heavier shot will usually finish the job better than using smaller shot.”

Smith expounded on other facets of the grand old sport of chasing wild turkeys, offering tips and hints that should be of value to other hunters, both neophytes as well as experienced hunters.

When to hunt

“While I enjoy hearing a gobbler sounding off from the roost, I have my best success hunting later in the day,” he said. “I’ve killed far more gobblers after 9 a.m. than I have off the roost. Many turkey hunters don’t even leave the truck if they listen and don’t hear a gobble. They’ll plan to come back another day when a gobbler gets vocal.

“Many times I’ve gone to the woods without hearing a solitary gobble off the roost. I just bide my time and don’t get impatient. There have been lots of times that I didn’t get one cranked up until 10 or 11 o’clock or later. I’ve found that if you hear one gobble on up in the day like that, you have a good chance at calling him in because he’s looking for company.”

Smith added that lots of turkey hunters play the early morning off-the-roost game with vocal gobblers, but once they fly down, shut up and head the other way, the hunt is over for those hunters for that day.

“That’s where patience comes in,” Smith said. “I don’t mind at all waiting until the other hunters leave the woods and things get quiet and back to normal. This is when you can sometimes get a gobbler interested.

“I’ll often stay in the woods until 1 p.m., come in for a bite and rest awhile, and I’m back in the woods by 3. I love to hunt afternoons, and I’ve had some good luck with those later-in-the-day gobblers.”

Calls and calling

“When I’m wanting a gobbler to respond so I’ll know where he is, I’ll often use a high-pitched friction call as a locater to get him started,” Smith said. “Once he answers, I’ll likely switch to a diaphragm or softer call to coax him on in.

“On a windy day, I’ll sometimes use a box call, which carries sound farther than some other types of calls. I like the old Ben Rodgers Lee type of mouth calls; you can make a sweet little yelp like a young hen or get a raspy sound like the boss hen. The situation dictates when I’ll use these.

“When I’m out early and hear a gobbler on the roost, I seldom call to him until he’s on the ground. I just don’t like to call to one on the roost as he’ll sometimes stay there and wait for the ‘hen’ he hears to show up. When one doesn’t, he loses interest, flies down and heads in another direction.

“If I’m calling in a bird and he hangs up out of range, I’ll go silent. I’ll wait 15 minutes or so, and then call very softly. Sometimes on a hung-up gobbler, I’ll turn my head away from him and yelp softly — sounding like the hen has lost interest and is leaving. Many times I’ve had them make a move and come on in when I try this tactic.”

Bag of tricks

“I’ll usually have at least six sets of old Ben Rodgers Lee style mouth callers, slate and glass friction calls and striker pegs of different materials,” Smith said. “I keep a box call in my vest for use especially on windy days. There will be my head net and gloves — maybe an extra set in case one gets misplaced — and I’ll have a light snack, maybe some cheese crackers and bottle of water, and I always have a compass with me.

“One cushion is attached to my vest, and I use it for my back. I’ll carry another to sit on. Comfort is important, and the longer you can sit without fidgeting, the better off you’ll be.”

Two things most turkey hunters feel they must have are binoculars and decoys. Smith seldom uses either.

“I hunt in the woods, and have found that binoculars are more a hindrance than a help to me in the woods,” he said. “I also rarely use a decoy because most of my hunting is in the woods. I’ve had times when a decoy has run a turkey off; they’ve done me more harm than good, so I usually don’t carry them with me.

“I do a lot of reading of turkey books and magazines, and find that this helps me learn things as well as reaffirm techniques that I’m already using.

“If I hear a turkey on the roost early mornings, he flies down and gobbles from a particular area but won’t come to my calls, I’ll go back to that same area in the afternoon and set up where the gobbler spent most of his time strutting and gobbling that morning. He apparently felt comfortable there earlier, and it’s probably a strut zone where he has successfully attracted hens to him in the past. I’ve killed several gobblers hunting that way.

“Another successful tactic I have utilized the last few years is what I do when I see a gobbler in the road. I drive on by and go half a mile or so before turning around, driving back about 300 yards past where I saw the bird run into the woods.

“I’ll take a path parallel to the way the turkey went and go a good distance before stopping to set up. I killed one of my longest-spurred gobblers five years ago on the Tensas National Wildlife Refuge in the afternoon. He crossed the road in front of me, I went half a mile before turning around and driving past where I’d last seen him. I went about 500 steps into the woods paralleling his travel route. I set up, and the second time I called, he gobbled. Two gobbles later, he was strutting in front of me at 30 steps.

“Another thing I’ve noticed is that I have good success by hunting the same spot year after year. I have several public-land areas in Louisiana and the other states I hunt where timber stands tend to stay the same year after year. At two of these spots, I actually have a favorite tree that I sit down by. I can just about depend on a gobbler being within a couple hundred yards of where I have killed other gobblers in past years. If an area is attractive to one gobbler, it will most likely be attractive to other gobblers in subsequent years.”

The tips offered by this 52-year-old master of the turkey woods should help hunters, both experienced and greenhorns. After all, Tommy Smith has slung 206 gobblers over his shoulder in his four decades of chasing these wily birds.