In 1907, President Teddy Roosevelt hunted bear in the thick Tensas swamp. His description of the terrain and the game available there give glimpses that make modern-day Bayou State hunters long for yesteryear.

The greatest sportsman ever to occupy the White House was Theodore Roosevelt, who served as president from 1901-1909.Roosevelt was a large, barrel-chested man who was equally at ease in high society or the wilds of Africa.

Born into a prominent New York family, he was educated at Harvard University, and became a successful author writing history books and magazine articles.

Becoming active in Republican Party politics, Roosevelt served as a New York legislator, New York City police commissioner and assistant secretary of the Navy before joining the Army during the Spanish-American War.

He then helped raise the famous Rough Riders, was appointed its second-in-command and led the regiment in battle up Cuba’s San Juan Hill. In the close-quarter fighting, Roosevelt killed at least one Spanish soldier with his pistol.

Emerging from the war as a genuine hero, Roosevelt was elected vice-president in 1900.

Roosevelt had a life-long zest for life. As a young man, he climbed the Matterhorn, worked as a cattle rancher and sheriff’s deputy in the Dakota Territory and hunted all over North America. In fact, Roosevelt was on a hunting trip in 1901 when he learned of President William McKinley’s assassination. Returning to Washington, he took the oath of office at the age of 42, making him the youngest president in American history.

Although a card-carrying member of the business-minded Republican Party, Roosevelt surprised everyone by becoming the nation’s first conservationist president. He set aside 230 million acres in national forests and reserves (including the Grand Canyon), and he created the National Forest Service.

Much of this conservation effort, as it turned out, took place in Louisiana. During his two terms of office, Roosevelt established four federal bird reservations here. Breton Island, created in 1904, was the nation’s second federal bird reservation and the only one Roosevelt ever personally visited. Breton Island became the forerunner of today’s federal wildlife preserve system.

Roosevelt’s most famous association with Louisiana, however, was a 1907 bear hunt. In October of that year, the president joined a number of notable state figures on a two-week hunt in East Carroll and Madison parishes.

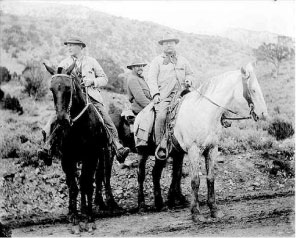

Among the party were John M. Parker and John A. McIlhenny. Parker, who later was courted to be Roosevelt’s running mate in the 1912 presidential race, was elected Louisiana’s governor in 1920. McIlhenny, of the Avery Island Tabasco Sauce family, had served as a Rough Rider officer and reportedly saved Roosevelt from a sniper’s bullet. Even the Navy’s surgeon general, Preston Marion Rixey, accompanied the president into the Louisiana swamps.

Acting as guide for the party was legendary bear hunter Ben Lilly. Lilly was born in Alabama in 1856, but moved to Morehouse Parish as a boy to live with an uncle. After trying his hand at various professions, he walked out on his wife and three children in 1901 and devoted the rest of his life to hunting. Before his death in 1936, Lilly had become a living legend in Louisiana, Mississippi and the Southwest.

Physically, Lilly was the epitome of the old-time Mountain Man. Tough as nails, he reportedly could pick up a 100-pound anvil and hold it effortlessly at arms’ length. Lilly also had a quirky belief that wet clothes should never be removed; they were to be left on the body to dry naturally.

With such a rough exterior, people were surprised to find Lilly a very mild-mannered man. He did not curse or drink coffee or alcohol, and Sundays were a day of rest. Lilly neither worked nor hunted on the Sabbath but read his Bible all day instead.

Sometime after Roosevelt’s 1907 bear hunt, Lilly moved west and worked for the federal government to remove such predators as bear, wolves and cougars. He hunted all over the Southwest, and by his retirement was said to have killed about 400 bears and 500 cougars. In his old age, Lilly lived on a New Mexico “poor farm” and died there in 1936. Today, there is a monument to the legendary bear hunter in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest near Silver City.

An equally fascinating member of the hunting party was 60-year-old Holt Collier. He handled the dogs and was said to have participated in killing over 3,000 bears in his lifetime. Born a slave, Collier had followed his master into Confederate service during the Civil War and actually fought the Yankees as a scout and sharpshooter.

Five years before the Louisiana hunt, Collier made history when he accompanied Roosevelt on a Mississippi bear hunt. When the president failed to bag a bear, Collier caught a cub and tied it to a tree so the president could shoot it. When Roosevelt refused the unsportsmanlike opportunity, the story made national news. A toy maker began marketing bear dolls to take advantage of the story’s popularity and received permission from Roosevelt to call them “Teddy Bears.”

Roosevelt’s 1907 bear hunt is still a topic of conversation among the people of Northeast Louisiana, and several place names remind us of the event.

In East Carroll Parish, a railroad switching station called O’Hara’s Switch was renamed Roosevelt, the Bear Lake area is still popular with hunters, and Teddy Roosevelt Lane is one of the local thoroughfares.

In 2004, there was an unsuccessful attempt by some residents to have the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge renamed for Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1908, Roosevelt wrote an article for Scribner’s magazine about his bear hunt entitled “In the Louisiana Canebrakes.” It is fascinating reading for all Louisiana sportsmen who dream what it was like to have hunted the vast Mississippi River bottomlands a century ago.

In the Louisiana Canebrakes

By PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT

In October, 1907, I spent a fortnight in the canebrakes of northern Louisiana, my hosts being Messrs. John M. Parker and John A. McIlhenny. Surgeon-General Rixey, of the United States Navy, and Dr. Alexander Lambert were with me.I was especially anxious to kill a bear in these canebrakes after the fashion of the old Southern planters, who for a century past have followed the bear with horse and hound and horn in Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas.

Our first camp was on Tensas Bayou. This is in the heart of the great alluvial bottomland created during the countless ages through which the mighty Mississippi has poured out of the heart of the continent. It is in the black belt of the South, in which the negroes outnumber the whites four or five to one, the disproportion in the region in which I was actually hunting being far greater.

There is no richer soil in all the earth; and when, as will soon be the case, the chances of disaster from flood are over, I believe the whole land will be cultivated and densely peopled.

At present the possibility of such flood is a terrible deterrent to settlement, for when the Father of Waters breaks his boundaries he turns the country for a breadth of 80 miles into one broad river, the plantations throughout all this vast extent being from 5 to 20 feet under water.

Cotton is the staple industry, corn also being grown, while there are a few rice fields and occasional small patches of sugar cane. The plantations are for the most part of large size and tilled by negro tenants for the white owners. Conditions are still in some respects like those of the pioneer days.

The magnificent forest growth which covers the land is of little value because of the difficulty in getting the trees to market, and the land is actually worth more after the timber has been removed than before. In consequence, the larger trees are often killed by girdling, where the work of felling them would entail disproportionate cost and labor.

At dusk, with the sunset glimmering in the west, or in the brilliant moonlight when the moon is full, the cottonfields have a strange spectral look, with the dead trees raising aloft their naked branches. The cottonfields themselves, when the bolls burst open, seem almost as if whitened by snow; and the red and white flowers, interspersed among the burst-open pods, make the whole field beautiful.

The rambling one-story houses, surrounded by outbuildings, have a picturesqueness all their own; their very looks betoken the lavish, whole-hearted, generous hospitality of the planters who dwell therein.

Beyond the end of cultivation towers the great forest. Wherever the water stands in pools, and by the edges of the lakes and bayous, the giant cypress loom aloft, rivaled in size by some of the red gums and white oaks. In stature, in towering majesty, they are unsurpassed by any trees of our eastern forests; lordlier kings of the green-leaved world are not to be found until we reach the sequoias and redwoods of the Sierras.

Among them grow many other trees — hackberry, thorn, honeylocust, tupelo, pecan and ash. In the cypress sloughs the singular knees of the trees stand 2 or 3 feet above the black ooze. Palmettos grow thickly in places.

The canebrakes stretch along the slight rises of ground, often extending for miles, forming one of the most striking and interesting features of the country. They choke out other growths, the feathery, graceful canes standing in ranks, tall, slender, serried, each but a few inches from his brother, and springing to a height of 15 or 20 feet.

They look like bamboos; they are well-nigh impenetrable to a man on horseback; even on foot they make difficult walking unless free use is made of the heavy bush-knife. It is impossible to see through them for more than 15 or 20 paces, and often for not half that distance. Bears make their lairs in them, and they are the refuge for hunted things.

Outside of them, in the swamp, bushes of many kinds grow thick among the tall trees, and vines and creepers climb the trunks and hang in trailing festoons from the branches. Here, likewise, the bush-knife is in constant play, as the skilled horsemen thread their way, often at a gallop, in and out among the great tree trunks, and through the dense, tangled, thorny undergrowth.

In the lakes and larger bayous we saw alligators and garfish; and monstrous snapping turtles, fearsome brutes of the slime, as heavy as a man, and with huge horny beaks that with a single snap could take off a man’s hand or foot. One of the planters with us had lost part of his hand by the bite of an alligator; and had seen a companion seized by the foot by a huge garfish from which he was rescued with the utmost difficulty by his fellow swimmers.

There were black bass in the waters, too, and they gave us many a good meal. Thick-bodied water moccasins, foul and dangerous, kept near the water; and farther back in the swamp we found and killed rattlesnakes and copperheads.

Coon and ‘possum were very plentiful, and in the streams there were minks and a few otters. Black squirrels barked in the tops of the tall trees or descended to the ground to gather nuts or gnaw the shed deer antlers — the latter a habit they shared with the wood rats.

To me the most interesting of the smaller mammals, however, were the swamp rabbits, which are thoroughly amphibious in their habits, not only swimming but diving, and taking to the water almost as freely as if they were muskrats. They lived in the depths of the woods and beside the lonely bayous.

Birds were plentiful. Mockingbirds abounded in the clearings, where, among many sparrows of more common kind, I saw the painted finch, the gaudily colored brother of our little indigo bunting, though at this season his plumage was faded and dim.

In the thick woods where we hunted there were many cardinal birds and winter wrens, both in full song. Thrashers were even more common; but so cautious that it was rather difficult to see them, in spite of their incessant clucking and calling and their occasional bursts of song.

There were crowds of warblers and vireos of many different kinds, evidently migrants from the North, and generally silent. The most characteristic birds, however, were the woodpeckers, of which there were seven or eight species, the commonest around our camp being the handsome red-bellied, the brother of the red-head which we saw in the clearings.

The most notable birds and those which most interested me were the great ivory-billed woodpeckers. Of these I saw three, all of them in groves of giant cypress; their brilliant white bills contrasted finely with the black of their general plumage. They were noisy but wary, and they seemed to me to set off the wildness of the swamp as much as any of the beasts of the chase.

Among the birds of prey the commonest were the barred owls, which I have never elsewhere found so plentiful. Their hooting and yelling were heard all around us throughout the night, and once one of them hooted at intervals for several minutes at mid-day. One of these owls had caught and was devouring a snake in the late afternoon, while it was still daylight. In the dark nights and still mornings and evenings their cries seemed strange and unearthly, the long hoots varied by screeches, and by all kinds of uncanny noises.

At our first camp our tents were pitched by the bayou. For four days the weather was hot, with steaming rains; after that it grew cool and clear. Huge biting flies, bigger than bees, attacked our horses, but the insect plagues, so veritable a scourge in this country during the months of warm weather, had well-nigh vanished in the first few weeks of the fall.

The morning after we reached camp we were joined by Ben Lilley, the hunter, a spare, full-bearded man, with mild, gentle, blue eyes and a frame of steel and whipcord. I never met any other man so indifferent to fatigue and hardship. He equalled Cooper’s Deerslayer in woodcraft, in hardihood, in simplicity — and also in loquacity.

The morning he joined us in camp, he had come on foot through the thick woods, followed by his two dogs, and had neither eaten nor drunk for 24 hours; for he did not like to drink the swamp water. It had rained hard throughout the night and he had no shelter, no rubber coat, nothing but the clothes he was wearing, and the ground was too wet for him to lie on; so he perched in a crooked tree in the beating rain, much as if he had been a wild turkey.

But he was not in the least tired when he struck camp; and, though he slept an hour after breakfast, it was chiefly because he had nothing else to do, inasmuch as it was Sunday, on which day he never hunted nor labored. He could run through the woods like a buck, was far more enduring, and quite as indifferent to weather, though he was over 50 years old.

He had trapped and hunted throughout almost all the half century of his life, and on trail of game he was as sure as his own hounds. His observations on wild creatures were singularly close and accurate. He was particularly fond of the chase of the bear, which he followed by himself, with one or two dogs; often he would be on the trail of his quarry for days at a time, lying down to sleep wherever night overtook him; and he had killed over 120 bears.

Late in the evening of the same day we were joined by two gentlemen, to whom we owed the success of our hunt. They were Messrs. Clive and Harley Metcalf, planters from Mississippi, men in the prime of life, thorough woodsmen and hunters, skilled marksmen, and utterly fearless horsemen.

For a quarter of a century they had hunted bear and deer with horse and hound, and were masters of the art. They brought with them their pack of bearhounds, only one, however, being a thoroughly stanch and seasoned veteran.

The pack was under the immediate control of a negro hunter, Holt Collier, in his own way as remarkable a character as Ben Lilley. He was a man of 60 and could neither read nor write, but he had all the dignity of an African chief, and for half a century he had been a bear hunter, having killed or assisted in killing over 3,000 bears.

He had been born a slave on the Hinds plantation, his father, an old man when he was born, having been the body-servant and cook of “old General Hinds,” as he called him, when the latter fought under Jackson at New Orleans.

When 10 years old Holt had been taken on the horse behind his young master, the Hinds of that day, on a bear hunt, when he killed his first bear. In the Civil War he had not only followed his master to battle as his body-servant, but had acted under him as sharpshooter against the Union soldiers.

After the war he continued to stay with his master until the latter died, and had then been adopted by the Metcalfs; and he felt that he had brought them up, and treated them with that mixture of affection and grumbling respect which an old nurse shows toward the lad who has ceased being a child. The two Metcalfs and Holt understood one another thoroughly, and understood their hounds and the game their hounds followed almost as thoroughly.

They had killed many deer and wild-cat, and now and then a panther; but their favorite game was the black bear, which, until within a very few years, was extraordinarily plentiful in the swamps and canebrakes on both sides of the lower Mississippi, and which is still found here and there, although in greatly diminished numbers.

In Louisiana and Mississippi the bears go into their dens toward the end of January, usually in hollow trees, often very high up in living trees, but often also in great logs that lie rotting on the ground. They come forth toward the end of April, the cubs having been born in the interval.

At this time the bears are nearly as fat, so my informants said, as when they enter their dens in January; but they lose their fat very rapidly.

On first coming out in the spring they usually eat ash buds and the tender young cane called mutton cane, and at that season they generally refuse to eat the acorns even when they are plentiful.

According to my informants it is at this season that they are most apt to take to killing stock, almost always the hogs which run wild or semi-wild in the woods. They are very individual in their habits, however; many of them never touch stock, while others, usually old he-bears, may kill numbers of hogs; in one case an old he-bear began this hog killing just as soon as he left his den.

In the summer months they find but little to eat, and it is at this season that they are most industrious in hunting for grubs, insects, frogs and small mammals. In some neighborhoods they do not eat fish, while in other places, perhaps not far away, they not only greedily eat dead fish, but will themselves kill fish if they can find them in shallow pools left by the receding waters.

As soon as the mast is on the ground they begin to feed upon it, and when the acorns and pecans are plentiful they eat nothing else, though at first berries of all kinds and grapes are eaten also. When in November they have begun only to eat the acorns they put on fat as no other wild animal does, and by the end of December a full-grown bear may weigh at least twice as much as it does in August, the difference being as great as between a very fat and a lean hog. Old he-bears which in August weigh 300 pounds and upward will toward the end of December weigh 600 pounds, and even more in exceptional cases.

Bears vary greatly in their habits in different localities, in addition to the individual variation among those of the same neighborhood. Around Avery Island, John McIlhenny’s plantation, the bears only appear from June to November; there they never kill hogs, but feed at first on corn and then on sugar-cane, doing immense damage in the fields, quite as much as hogs would do.

But when we were on the Tensas we visited a family of settlers who lived right in the midst of the forest 10 miles from any neighbors; and although bears were plentiful around them they never molested their corn-fields — in which the coons, however, did great damage.

A big bear is cunning, and is a dangerous fighter to the dogs. It is only in exceptional cases, however, that these black bears, even when wounded and at bay, are dangerous to men, in spite of their formidable strength.

Each of the hunters with whom I was camped had been charged by one or two among the scores or hundreds of bears he had slain, but no one of them had ever been injured, although they knew other men who had been injured. Their immunity was due to their own skill and coolness; for when the dogs were around the bear the hunter invariably ran close in so as to kill the bear at once and save the pack.

Each of the Metcalfs had on one occasion killed a large bear with a knife, when the hounds had seized it and the man dared not fire for fear of shooting one of them. They had in their younger days hunted with a General Hamberlin, a Mississippi planter whom they well knew, who was then already an old man. He was passionately addicted to the chase of the bear, not only because of the sport it afforded, but also in a certain way as a matter of vengeance; for his father, also a keen bear-hunter, had been killed by a bear.

It was an old he, which he had wounded and which had been bayed by the dogs; it attacked him, throwing him down and biting him so severely that he died a couple of days later. This was in 1847.

A large bear is not afraid of dogs, and an old he, or a she with cubs, is always on the lookout for a chance to catch and kill any dog that comes near enough.

While lean and in good running condition it is not an easy matter to bring a bear to bay; but as they grow fat they become steadily less able to run, and the young ones, and even occasionally a full-grown she, will then readily tree. If a man is not near by, a big bear that has become tired will treat the pack with whimsical indifference.

The Metcalfs recounted to me how they had once seen a bear, which had been chased quite a time, evidently make up its mind that it needed a rest and could afford to take it without much regard for the hounds. The bear accordingly selected a small opening and lay flat on its back with its nose and all its four legs extended. The dogs surrounded it in frantic excitement, barking and baying, and gradually coming in a ring very close up.

The bear was watching, however, and suddenly sat up with a jerk, frightening the dogs nearly into fits. Half of them turned back-somersaults in their panic, and all promptly gave the bear ample room. The bear having looked about, lay flat on its back again, and the pack gradually regaining courage once more closed in. At first the bear, which was evidently reluctant to arise, kept them at a distance by now and then thrusting an unexpected paw toward them; and when they became too bold it sat up with a jump and once more put them all to flight.

For several days we hunted perseveringly around this camp on the Tensas Bayou, but without success. Deer abounded, but we could find no bear; and of the deer we killed only what we actually needed for use in camp. I killed one myself by a good shot, in which, however, I fear that the element of luck played a considerable part.

We had started as usual by sunrise, to be gone all day; for we never counted upon returning to camp before sunset. For an hour or two we threaded our way, first along an indistinct trail, and then on an old disused road, the hardy woods horses keeping on a running walk without much regard to the difficulties of the ground. The disused road lay right across a great canebrake, and while some of the party went around the cane with the dogs, the rest of us strung out along the road so as to get a shot at any bear that might come across it.

I was following Harley Metcalf, with John McIlhenny and Dr. Rixey behind on the way to their posts, when we heard in the far-off distance two of the younger hounds, evidently on the trail of a deer.

Almost immediately afterward a crash in the bushes at our right hand and behind us made me turn around, and I saw a deer running across the few feet of open space; and as I leaped from my horse it disappeared in the cane. I am a rather deliberate shot, and under any circumstances a rifle is not the best weapon for snap shooting, while there is no kind of shooting more difficult than on running game in a canebrake.

Luck favored me in this instance, however, for there was a spot a little ahead of where the deer entered in which the cane was thinner, and I kept my rifle on its indistinct, shadowy outline until it reached this spot; it then ran quartering away from me, which made my shot much easier, although I could only catch its general outline through the cane. But the 45-70 which I was using is a powerful gun and shoots right through cane or bushes; and as soon as I pulled the trigger the deer, with a bleat, turned a tremendous somersault and was dead when we reached it.

I was not a little pleased that my bullet should have sped so true when I was making my first shot in company with my hard-riding, straight-shooting planter friends.

But no bear were to be found. We waited long hours on likely stands. We rode around the canebrakes through the swampy jungle, or threaded our way across them on trails cut by the heavy wood-knives of my companions; but we found nothing.

Until the trails were cut the canebrakes were impenetrable to a horse and were difficult enough to a man on foot. On going through them it seemed as if we must be in the tropics; the silence, the stillness, the heat, and the obscurity, all combining to give a certain eeriness to the task, as we chopped our winding way slowly through the dense mass of close-growing, feather-fronded stalks.

Each of the hunters prided himself on his skill with the horn, which was an essential adjunct of the hunt, used both to summon and control the hounds, and for signalling among the hunters themselves. The tones of many of the horns were full and musical; and it was pleasant to hear them as they wailed to one another, backward and forward, across the great stretches of lonely swamp and forest.

A few days convinced us that it was a waste of time to stay longer where we were. Accordingly, early one morning we hunters started for a new camp 15 or 20 miles to the southward, on Bear Lake. We took the hounds with us, and each man carried what he chose or could in his saddle-pockets, while his slicker was on his horse’s back behind him. Otherwise we took absolutely nothing in the way of supplies, and the negroes with the tents and camp equipage were three days before they overtook us.

On our way down we were joined by Major Amacker and Dr. Miller, with a small pack of cathounds. These were good deer dogs and they ran down and killed on the ground a goodsized bobcat — a wildcat, as it is called in the South. It was a male and weighed 23 1/2 pounds. It had just killed and eaten a large rabbit. The stomachs of the deer we killed, by the way, contained acorns and leaves.

Our new camp was beautifully situated on the bold, steep bank of Bear Lake — a tranquil stretch of water, part of an old river-bed, a couple of hundred yards broad, with a winding length of several miles. Giant cypress grew at the edge of the water, the singular cypress knees rising in every direction round about, while at the bottoms of the trunks themselves were often cavernous hollows opening beneath the surface of the water, some of them serving as dens for alligators. There was a waxing moon, so that the nights were as beautiful as the days.

From our new camp we hunted as steadily as from the old. We saw bear sign, but not much of it, and only one or two fresh tracks. One day the hounds jumped a bear, probably a yearling from the way it ran; for at this season a yearling or a 2-year-old will run almost like a deer, keeping to the thick cane as long as it can and then bolting across through the bushes of the ordinary swamp land until it can reach another canebrake.

After a three hours’ run this particular animal managed to get clear away without one of the hunters ever seeing it, and it ran until all the dogs were tired out. A day or two afterward one of the other members of the party shot a small yearling — that is, a bear which would have been 2 years old in the following February. It was very lean, weighing but 55 pounds. The finely-chewed acorns in its stomach showed that it was already beginning to find mast.

We had seen the tracks of an old she in the neighborhood, and the next morning we started to hunt her out. I went with Clive Metcalf. We had been joined overnight by Mr. Ichabod Osborn and his son Tom, two Louisiana planters, with six or eight hounds — or rather bear dogs, for in these packs most of the animals are of mixed blood, and, as with all packs that are used in the genuine hunting of the wilderness, pedigree counts for nothing as compared with steadiness, courage, and intelligence. There were only two of the new dogs that were really stanch bear dogs.

The father of Ichabod Osborn had taken up the plantation upon which they were living in 1811, only a few years after Louisiana became part of the United States, and young Osborn was now the third in line from father to son who had steadily hunted bears in this immediate neighborhood.

On reaching the cypress slough near which the tracks of the old she had been seen the day before, Clive Metcalf and I separated from the others and rode off at a lively pace between two of the canebrakes.

After an hour or two’s wait, we heard, very far off, the notes of one of the loudest-mouthed hounds, and instantly rode toward it, until we could make out the babel of the pack. Some hard galloping brought us opposite the point toward which they were heading — for experienced hunters can often tell the probable line of a bear’s flight, and the spots at which it will break cover.

But on this occasion the bear shied off from leaving the thick cane and doubled back; and soon the hounds were once more out of hearing, while we galloped desperately around the edge of the cane.

The tough woods-horses kept their feet like cats as they leaped logs, plunged through bushes, and dodged in and out among the tree trunks; and we had all we could do to prevent the vines from lifting us out of the saddle, while the thorns tore our hands and faces. Hither and thither we went, now at a trot, now at a run, now stopping to listen for the pack. Occasionally we could hear the hounds, and then off we would go racing through the forest toward the point for which we thought they were heading.

Finally, after a couple of hours of this, we came up on one side of a canebrake on the other side of which we could hear not only the pack but the yelling and cheering of Harley Metcalf and Tom Osborn and one or two of the negro hunters, all of whom were trying to keep the dogs up to their work in the thick cane.

Again we rode ahead, and now in a few minutes were rewarded by hearing the leading dogs come to bay in the thickest of the cover. Having galloped as near to the spot as we could, we threw ourselves off the horses and plunged into the cane, trying to cause as little disturbance as possible, but of course utterly unable to avoid making some noise.

Before we were within gunshot, however, we could tell by the sounds that the bear had once again started, making what is called a “walking bay.” Clive Metcalf, a finished bear hunter, was speedily able to determine what the bear’s probable course would be, and we stole through the cane until we came to a spot near which he thought the quarry would pass. Then we crouched down, I with my rifle at the ready. Nor did we have long to wait.

Peering through the thick-growing stalks I suddenly made out the dim outline of the bear coming straight toward us; and noiselessly I cocked and half-raised my rifle, waiting for a clearer chance. In a few seconds it came; the bear turned almost broadside to me, and walked forward very stiff-legged, almost as if on tiptoe, now and then looking back at the nearest dogs.

These were two in number — Rowdy, a very deep-voiced hound, in the lead, and Queen, a shrill-tongued brindled bitch, a little behind. Once or twice the bear paused as she looked back at them, evidently hoping that they would come so near that by a sudden race she could catch one of them. But they were too wary.

All of this took but a few moments, and as I saw the bear quite distinctly some 20 yards off, I fired for behind the shoulder. Although I could see her outline, yet the cane was so thick that my sight was on it and not on the bear itself. But I knew my bullet would go true; and, sure enough, at the crack of the rifle the bear stumbled and fell forward, the bullet having passed through both lungs and out at the opposite side.

Immediately the dogs came running forward at full speed, and we raced forward likewise lest the pack should receive damage. The bear had but a minute or two to live, yet even in that time more than one valuable hound might lose its life; so when within half a dozen steps of the black, angered beast, I fired again, breaking the spine at the root of the neck; and down went the bear stark dead, slain in the canebrake in true hunter fashion.

One by one the hounds struggled up and fell on their dead quarry, the noise of the worry filling the air. Then we dragged the bear out to the edge of the cane, and my companion wound his horn to summon the other hunters.

This was a big she-bear, very lean, and weighing 202 pounds. In her stomach were palmetto berries, beetles and a little mutton cane, but chiefly acorns chewed up in a fine brown mass.

John McIlhenny had killed a she-bear about the size of this on his plantation at Avery’s Island the previous June. Several bear had been raiding his corn-fields, and one evening he determined to try to waylay them. After dinner he left the ladies of his party on the gallery of his house while he rode down in a hollow and concealed himself on the lower side of the corn-field.

Before he had waited 10 minutes a she-bear and her cub came into the field. The she rose on her hind legs, tearing down an armful of ears of corn which she seemingly gave to the cub, and then rose for another armful. McIlhenny shot her; tried in vain to catch the cub; and rejoined the party on the veranda, having been absent but one hour.

After the death of my bear I had only a couple of days left. We spent them a long distance from camp, having to cross two bayous before we got to the hunting grounds. I missed a shot at a deer, seeing little more than the flicker of its white tail through the dense bushes; and the pack caught and killed a very lean 2-year-old bear weighing eighty pounds.

Near a beautiful pond called Panther Lake we found a deer-lick, the ground not merely bare, but furrowed into hollows by the tongues of the countless generations of deer that had frequented the place. We also passed a huge mound, the only hillock in the entire district; it was the work of man, for it had been built in the unknown past by those unknown people whom we call mound-builders.

On the trip, all told, we killed and brought into camp three bear, six deer, a wildcat, a turkey, a possum, and a dozen squirrels; and we ate everything except the wildcat. In the evenings we sat around the blazing camp-fires, and, as always on such occasions, each hunter told tales of his adventures and of the strange feats and habits of the beasts of the wilderness.

There had been beaver all through this delta in the old days, and a very few are still left in out-of-the-way places. One Sunday morning we saw two wolves, I think young of the year, appear for a moment on the opposite side of the bayou, but they vanished before we could shoot. All of our party had had a good deal of experience with wolves. The Metcalfs had had many sheep killed by them, the method of killing being invariably by a single bite which tore open the throat while the wolf ran beside his victim.

The wolves also killed young hogs, but were very cautious about meddling with an old sow; while one of the big half-wild boars that ranged free through the woods had no fear of any number of wolves. Their endurance and the extremely difficult nature of the country made it difficult to hunt them, and the hunters all bore them a grudge, because if a hound got lost in a region where wolves were at all plentiful they were almost sure to find and kill him before he got home. They were fond of preying on dogs, and at times would boldly kill the hounds right ahead of the hunters.

In one instance, while the dogs were following a bear and were but a couple of hundred yards in front of the horsemen, a small party of wolves got in on them and killed two. One of the Osborns, having a valuable hound which was addicted to wandering in the woods, saved him from the wolves by putting a bell on him. The wolves evidently suspected a trap and would never go near the dog.

On one occasion another of his hounds got loose with a chain on, and they found him a day or two afterward unharmed, his chain having become entangled in the branches of a bush. One or two wolves had evidently walked around and around the imprisoned dog, but the chain had awakened their suspicions and they had not pounced on him. They had killed a yearling heifer a short time before, on Osborn’s plantation, biting her in the hams.

It has been my experience that foxhounds as a rule are afraid of attacking a wolf; but all of my friends assured me that their dogs, if a sufficient number of them were together, would tackle a wolf without hesitation; the packs, however, were always composed, to the extent of at least half, of dogs which, though part hound, were part shepherd or bull or some other breed.

Dr. Miller had hunted in Arkansas with a pack specially trained after the wolf. There were 28 of them all told, and on this hunt they ran down and killed unassisted four full-grown wolves, although some of the hounds were badly cut.

None of my companions had ever known of wolves actually molesting men, but Mr. Ichabod Osborn’s son-in-law had a queer adventure with wolves while riding alone through the woods one late afternoon. His horse acting nervously, he looked about and saw that five wolves were coming toward him. One was a bitch, the other four were males. They seemed to pay little heed to him, and he shot one of the males, which crawled off. The next minute the bitch ran straight toward him and was almost at his stirrup when he killed her. The other three wolves, instead of running away, jumped to and fro, growling, with their hair bristling, and he killed two of them; whereupon the survivor at last made off. He brought the scalps of the three dead wolves home with him.

Near our first camp was the carcass of a deer, a yearling buck, which had been killed by a cougar. When first found, the wounds on the carcass showed that the deer had been killed by a bite in the neck at the back of the head; but there were scratches on the rump as if the panther had landed on its back.

One of the negro hunters, Brutus Jackson, evidently a trustworthy man, told me that he had twice seen cougars, each time under unexpected conditions. Once he saw a bobcat race up a tree, and riding toward it saw a panther reared up against the trunk. The panther looked around at him quite calmly, and then retired in leisurely fashion. Jackson went off to get some hounds and when he returned two hours afterward the bobcat was still up the tree, evidently so badly scared that he did not wish to come down. The hounds were unable to follow the cougar.

On another occasion he heard a tremendous scuffle and immediately afterward saw a big doe racing along with a small cougar literally riding it. The cougar was biting the neck, but low down near the shoulders; he was hanging on with his front paws, but was tearing away with his hind claws, so that the deer’s hair appeared to fill the air. As soon as Jackson appeared the panther left the deer. He shot it, and the doe galloped off, apparently without serious injury.