Hunters across the state schedule their vacation time to coincide with the rut, but what are bucks really doing? Is the rut the best time to be in the woods?

The buck hadn’t stopped for more than a few minutes in days, and was simply worn out. The 10-point had been busy chasing does and taking care of business, leaving little time for concern over its physical health. But just as a college binge eventually winds down, the buck finally turned its thoughts to a bit of rest after a hard night of carousing that extended well into the daylight hours.

So the buck finally broke off its pursuit of love about mid afternoon, and headed for the safety and comfort of its bedding thicket. The deer could barely hold up its head as it plodded toward home.

And then a sharp, tantalizingly seductive smell filled the deer’s nose.

Excitement surged through the deer, and its head snapped up. A hot doe had passed this way recently. Very recently.

The temptress that had walked this trail obviously was all dolled up, perfumed and ready for some action. Olfactory sensors in the bucks nose pumped signals to the brain, overriding all instincts for self-preservation.

Only a few hundred yards away from the promise of rest, the buck turned and trotted after the doe in hopes of curing the hangover of too many wakeful hours with some hair of the dog.

Patrick and Chandler Kelleher were visiting Lottie Hunting Club, with the goal of getting 10-year-old Chandler a shot at a buck.

The rules of the club, which carefully manages its bucks, were weighted decidedly in the favor of the young hunter: All normal antler criteria were waived, so his first buck could be anything with calcium sticking above its head.

The Kellehers were sent to a box stand positioned at an intersection of two pipelines, providing sweeping views in four directions.

“We looked in different directions,” Patrick Kelleher said. “I gave him the downwind zone, and I watched the other direction.”

Any shot would have to come from the openings of those pipelines, which cut through the jungle of a large cutover. And the elder Kelleher knew he would have to help his son quickly get on any buck walking across the 60-yard openings.

The buck pushed its way through the thickets, refusing to give up on the hot doe that couldn’t be far ahead. Finally, it caught sight of the beauty. But she wasn’t alone, predictably traveling with a girlfriend.

The two does moved at a clip, and right on their heels was another buck. This was a small deer, obviously trying to make an easy score.

Nostrils flared, and ears cocked back as jealousy coursed through the 10-pointer’s veins. It stepped up the pace, and closed the distance on the young buck, intent on administering a hard, physical lesson.

The does looked back just in time to see their young paramour turn. It had heard or sensed the older buck’s approach, and wheeled to meet the challenge.

It was never really a contest. The young buck lacked the experience, the rack, the power or the nerve to put up much of a fight. Its initial bluster quickly dissipated, and it ceded the does to its superior.

After watching the young buck scamper into the surrounding cover, the 10-point turned its attention back to the does. They were nowhere to be seen, but that wasn’t a problem. The cloying perfume lingered in the air, marking the route as clearly as any GPS.

The chase resumed, with the buck’s confidence bolstered by the brief battle and the earlier sighting of the doe. With new vigor, the deer trotted along as if drawn by a string.

A few deer were way down the rights of way, taking advantage of the food plots. A couple of bucks had already crossed the pipelines, but most were too far for any shot.

Those that were closer were allowed to walk, with Kelleher holding his son back because the bucks were young.

“I wasn’t going to burn the invitation on a little deer,” he chuckled.

And then young Chandler nudged his father: A couple of does were slipping across one of the openings about 130 yards out.

“Their tails were flopping up, looking like they do during the rut,” Patrick Kelleher said. “You could see they were ready — not alerted, but how they do their tails during the rut.”

The hunters’ vigilance increased. They continued to watch does filter across the four shooting lanes, but Chandler Kelleher never took his eyes off the spot from which the hot does had emerged.

The buck briefly caught site of the does again, but the deer slowed and finally came to a stop. A nagging doubt began taking the edge off the crazed desire to procreate.

What was the problem? Instinct seemed to be telling the deer to go no farther. But the competing drive of the rut was an almost physical tug forward.

The buck took a few tentative steps, and stopped again. There was no ignoring the vague worry.

After a few agonizing moments, the deer dipped its head and caught another powerful dose of the doe’s perfume.

Indecision ended in that intoxicating smell, and the buck continued the pursuit.

However, soon the doubt returned.

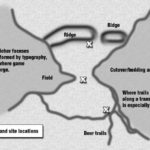

Ahead, the buck could see the end of the thick cover. It knew a wide-open stretch of ground was ahead, and experience had long ago taught the deer that such exposure brought inherent risk.

While the need to catch the focus of its affection spurred the buck forward, it approached the opening with extreme caution.

After checking things out from the relative safety of the thicket, the buck stuck its head out into the pipeline to get a better look.

Deer were scattered down the right of way, and everything looked safe.

With another couple of steps, the buck was fully in the opening.

The elder Kelleher heard excitement in his son’s voice.

“Dad, there’s one there,” Chandler Kelleher whispered.

Turning, Patrick Kelleher saw a buck just standing there.

“I looked and thought, ‘Damn,’” Kelleher said. “It was standing right in the same trail as those does were walking on.”

He raised his binoculars, but didn’t take too long to decide it was a shooter.

“I could see he was outside the ears and 10 points,” he said. “I said, ‘Alright buddy, let’s shoot.’”

Patrick Kelleher helped position the .270-caliber rifle, holding the front of the gun to try and mitigate any kick.

Chandler put his small frame in position, and stared into the scope.

“The deer just started walking,” Patrick Kelleher said. “I said, ‘Alright, man, shoot. Just shoot him.’”

The young hunter, however, was having difficulty.

“I can’t find him. I can’t find him,” said the youngster, obvious agitation creeping into his voice.

By this time, the buck was moving steadily across the pipeline, heading for the safety of the thicket and the promise of feminine company on the other side.

“The deer was literally about 4 yards from going in the woods, and I said, ‘Come on, buddy, pull it together,’” Patrick Kelleher said.

Just before the deer made the crossing, the rifle bucked.

After standing for a brief moment of assessment, the buck was ready to continue the chase. The urgency had waned a bit, however, and the deer simply walked calmly toward the other side of the opening.

It ignored everything else, keeping its focus on where the scent trail disappeared into the woods.

Another few steps, and all thoughts of danger would be over.

But a thunderous scream accompanied by a piercing pain in its side erased the relief of a second earlier. The deer jumped to escape the pain, and bounded the final few yards into the woods.

It didn’t go far. Just inside the woods, all thoughts of consummating a relationship with the doe were forgotten as fatigue and pain forced the buck to stop and lay down. Just a few minutes of rest, and everything will be fine.

When the gun bucked, Patrick Kelleher was confident.

“The thing did the old jump-up, and it ran into the woods,” he said. “I told him to get ready because (the buck) might come running out onto the other pipeline.”

After nothing appeared during the next 30 minutes, the father-son team climbed from the stand and hurrired to where the buck disappeared.

“We go walking up right about dark to where the trail was, and we get right to the edge of the pipeline and a deer jumps up probably 10 yards from the pipeline and starts walking into the woods,” Patrick Kelleher said.

The hunters backed away and headed to the camp to give the deer time to lay up again, hopefully this time for good.

With the mercury falling into a frigid night, Patrick Kelleher decided to wait until the morning to go follow the trail.

“I hated to push this deer,” Kelleher said. “It’s 30 degrees, so I thought, ‘Let’s just let the deer lay.’”

Movement in the nearby opening startled the buck, pushing it to its feet. However, there was no energy left for a bounding escape.

So the deer limped away, trying to ignore the tenderness of it wound and shortness of breath.

However, it just couldn’t go very far, and settled down again in less than 100 yards.

Breathing became more difficult, and the buck briefly decided to nap in hopes of recouping some energy. Before it drifted off, however, panic set in.

Kicking in vain attempts to regain its feet, the deer’s eyes dulled, and the animal drifted away.

The next morning was a school day, and Chandler Kelleher wasn’t cut any slack.

“I made him go to school,” father Patrick laughed. “He was like, ‘Come on, Dad.’ But I made him go.”

Patrick Kelleher hurried back to the club, and quickly made his way to the pipeline. After locating the trail, he stepped into the thicket and found blood — lots of blood — where the deer had laid up just off the right of way.

“That was where the deer got up the evening before,” Kelleher said.

The blood trail was easy to follow after that, and not 80 yards away, he found his son’s trophy.

“He made me leave it whole, so he could see how big he was,” Patrick Kelleher said.

The buck eventually scored out at 126 Boone & Crockett

points.