According to an amazing LSU telemetry study, getting that trophy buck’s address is a lot easier than most hunters think.

Keith Barre watched a couple of 8-points on his Washington Parish lease grow, consistently collecting pictures of them from trail cameras. The bucks were small baskets two seasons ago, but had reached shooter proportions by the opening of the 2007 hunting season.

“They were like brothers,” Barre said.

One of the bucks was captured over and over at the same camera between fall of 2006 and winter of 2008, and the second buck was consistently seen on cameras in the same area.

Last year, that second deer — a 17-inch 8-point weighing 200 pounds — was killed by another hunter only 500 yards from Barre’s stand site. The other one is still there.

“I know he’s still alive because I’ve gotten pictures of him this year,” the Covington hunter said.

He’s also tracking via a camera another buck that regularly walks the edge of a green patch.

“I’ve got a stand on that food plot, and I’ve never seen this buck (on the plot),” Barre said. “He basically is traveling right off the edge of the food plot in the edge of the woods.

“This year I think I’m going to move my stand into the woods where there are a couple of trails that converge.”

That’s exactly the right thing to do, according to an LSU grad student.

Justin Thayer has been conducting a deer telemetry study on property west of Baton Rouge in cooperation with the LSU AgCenter’s School of Renewable Natural Resources, the Department of Wildlife & Fisheries and the Quality Deer Management Association. He said Barre probably is locked in on those two bucks’ preferred living quarters.

“The earlier you locate a buck, that area is going to be your high-percentage area for killing that deer,” Thayer said. “You know that they’re going to be back there.”

That goes against traditional thought, which holds that the rut is the best time of the season to bag mature bucks.

“During the rut, what we see is (deer) would make big movements,” he said. “They are much less predictable then. (A buck) might be in one area one day, and never be back there.

“Outside of the rut, those deer are much more predictable.”

What Thayer has found by trapping and fitting 37 bucks and 11 does with tracking collars over the past two years is that bucks have very distinct home ranges.

“Throughout the year, 95 percent of the time they’ll be inside that home range,” he said.

What has surprised Thayer, a lifelong hunter himself, are the sizes of the home ranges. For instance, one 3½-year-old buck has a home range of only 156 acres. Others have home territories topping 400 acres, but that’s still not as large as many hunters believe.

“I always believed deer had larger home ranges than we’re finding here,” Thayer said.

Another surprising preliminary fact arising during the study is that bucks’ territories often overlap.

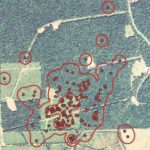

For instance, the home ranges for four tracked bucks ranging from 2½ to 3½ years old all center around a set of cutovers on the West Baton Rouge Parish property on which the study is being performed.

“Any of the deer we caught close to those cutovers just love them,” Thayer said.

The study property, owned by Wilbert & Sons L.L.C, is bottomland hardwood, so this could be because the cutovers provide more cover than the open woods.

“As far as where they’re going to spend most of their time, they’re going to be where they feel safe,” Thayer said.

A new telemetry study will begin next year to determine whether home ranges in piney woods are similar, Thayer said.

Photos captured by Barre seem to back up Thayer’s preliminary findings that bucks will share territory. The deer, the same ones he believes are siblings, have been captured by a group of cameras in the same areas. Barre refers to the buck that’s still alive as Buck B, and the 8-pointer killed 500 yards from Barre’s cameras is referred to as Buck C.

“I believe (one) camera location is the core of Deer B’s home range,” Barre said. “He was photographed at least 18 different times here during the fall of ’06 through winter of ’08. I believe Deer C’s home range (was) just to the east of Deer B’s range, and he occasionally overlaps into Deer B’s range.”

Thayer said initial review of his study data indicates there are, indeed, smaller areas within each deer’s home range in which that deer spends a lot of time. That means Barre probably is spot on about having found Buck B’s core.

“Deer have core areas within their home ranges in which 50 percent of the time they are inside their home ranges, that’s where they are going to be,” Thayer said. “That means if you flip a coin, you’ll be correct half of the time if you said a buck will be in its core area.”

A particluar core area can be extremely close to that of competing bucks. Three bucks in the study, for instance, established core areas in a single 40-acre cutover.

“They split the cutover up, with each taking a small section of it as their core area,” Thayer explained. “They kind of distribute themselves around that cutover.”

In fact, preliminary figures show core ranges average only about 40 acres.

And here’s yet another important finding: Bucks come right back to these areas each time they’re pushed out.

Thayer said four bucks and two does in the study maintained home ranges within a 300-acre area bordered by the Intracoastal Waterway and another large bayou. This was one of the favorite rabbit-hunting areas for the hunting club leasing the land, and Thayer said the deer would quickly vacate the property when dogs and hunters moved through the area.

They didn’t stay away long, however.

“They’d cross the Intracoastal Waterway (during the rabbit hunts), and we’d come back the next morning, and they’d be right back in their home ranges,” Thayer said. “That happened probably a dozen times.”

That tells Thayer that bucks are very predictable, and simply don’t like to move as much as we are taught.

“I can hunt these deer with grenades,” Thayer chuckled. “Without any equipment, I can go in and just chunk grenades into (specific) thickets and, of the 36 deer in the study, I could come back with 12 to 15 of them.”

That’s all incredible information, but how is it applicable to hunting?

Thayer believes hunters can absolutely dial in on bucks by getting in the woods early and finding out where they spend their time.

“If you can find that core area or close to that core area, that deer’s going to be there the majority of the time,” he said. “If you can find that deer’s core area, you’ve got that buck’s address; you’ve got that deer’s number.”

That should change the way most of us approach hunting.

For instance, Thayer believes hunters should be spending time in the woods during the offseason narrowing down where deer live.

That’s something Barre said is important to him.

“I start at the end of the season,” he said. “I’m pretty much one of those obsessed deer hunters.”

The focus during this time of year is finding new areas in which he might want to hunt the following season.

“I’m looking for sheds, old scraps and rubs, and I’m checking for tracks in the ditches where deer cross the roads (on the lease),” Barre said.

When he finds a “tunnel” in the brush where deer are obviously traveling regularly, Barre bails off the road and follows the trail as far as he can.

“I’ve been known to get on my hands and knees to crawl through the briars,” he chuckled. “If I get through with scouting (for the day) and I’m not full of scratches from the briars, I’m not doing my job.”

While he spends a lot of time prowling the woods during the offseason, trail cameras are a vital part of Barre’s scouting.

“I put them out on well-used trails to see what’s moving through the area,” he said. “I go out periodically and check them.

“I typically have five or six cameras out.”

Once Barre has captured an image of a good deer, he uses the cameras to better understand that buck’s movements.

“I generally keep (the cameras) in the same vicinity,” he said. “I try to identify what’s out there in February and watch them until the next season.”

Another part of his offseason scouting routine is using U.S. Geological Survey maps and aerials downloaded from Google Earth.

“You can see things from the air you can’t see from the ground,” Barre said. “You might see an old logging road that you didn’t know was there. You just push through the brush until the road opens up and, sure enough, you can find things in there.”

At this time of year, Barre doesn’t even worry about bumping deer.

“I don’t think it’s a problem that early,” he said.

He simply puts in a camera or two to figure out if that’s where the deer spends most of its time.

Of course, Barre is hunting on private land. That means it’s fairly controlled and he doesn’t have to compete with piles of hunters.

Public-land hunting is different.

Addis hunter Dave Guidry spends most of his hunting time on Sherburne Wildlife Mangement Area, but also will hunt Tunica and Pearl River WMAs. So he can’t use cameras, and he doesn’t spend much time in the woods during the summer.

“It’s just too hot to get out there,” he said.

So he uses bowseason to scout.

“I sit a stand for a few hours, and then I get down and start walking,” Guidry said.

Guidry’s approach is to keep things simple.

“I’m looking for a spot that’s not going to have a lot of pressure,” he said.

Feeding and cover areas are central to Guidry’s strategy.

“I look for activity under feed trees (persimmons and oaks),” he said.

While tracks are fine, he actually believes droppings are more telling.

“I’m looking on the ground for deer droppings — fresh, shiny deer droppings,” he said. “And I’m not looking for random droppings. I want to see two to three piles in an area. Deer are going to make droppings wherever they are, and there will be more droppings where they spend the most time.

“That seems simple, but a lot of people over-think it.”

He said cutovers in the overall openness of Sherburne are also prime.

“Sherburne is just so vast with the same woods, so cutovers provide something that’s different,” Guidry said.

The problem with these cutovers is that they stick out like sore thumbs, so they can get crowded.

“Once you get a doe day, there are so many people in these cutovers it ruins them,” he said.

So Guidry said he and his buddies have found an effective way of using that hunting pressure.

“We started hunting the ‘best’ deer spots, and come doe weekend we’d be looking at 10 people, either hunting the area or walking around,” he said. “So we started finding (nearby) spots that didn’t have many people. There was not much browse, the ground would be mush: It was the ‘wrong’ spot.”

However, they set up stands, and as the pressure of the crowds pushed deer out of their preferred areas, Guidry said they started seeing deer.

“By the time they get in our area, they’re starting to slow down,” he said. “Basically, we like to let people push deer to us.

“We find a thicket where there are a lot of flags, and we look for those little pockets or corners that are overlooked.”

And he said that can provide repeated opportunities for shots.

“I watched one doe run by four times,” Guidry said. “It went one way, and then it came back the other way.”

After either-sex season, Guidry heads as far into the woods as possible so he’s not competing with other bucks-only hunters.

“We carry a pirogue on a four-wheeler to a bayou, and use the pirogue to cross the bayou,” he said. “Then we take off walking.

“We walk a mile. I’m looking for other people’s flags. I’ll keep walking until I don’t see any more flags.”

Once there, the goal is to find places deer will be pushed when the crowds show up.

“I’m looking for a spot where I’ve got one spot to shoot them on a trail,” Guidry said.

These thick areas make it easier to pattern deer than in the open woods, as well.

“It’s easier to find a trail in a thick spot,” Guidry explained. “We’re looking for secluded areas hard to get to.”

Striped oaks are his target in these areas.

“Almost every buck that I’ve seen checked in (at the WMA headquarters) had striped oaks in its belly,” Guidry said.

In keeping with his simple approach, the telling sign of deer activity under these trees is feces.

“If you’ve got acorns and no droppings, there’s no sense in hunting the tree because the deer aren’t feeding there,” Guidry said.

Once an active feed tree is located, it’s time to find the perfect spot to ambush deer.

“At that point, we’re not looking for the worst spot: We’re looking for the best spot,” Guidry said.

That means he wants to locate the cover areas deer use to travel with confidence.

“I’ll usually make a big circle around the tree and see if there’s a thicket or a ditch they might be following, and then I’ll look for a well-used (game) trail,” he said.

The key, whether hunting public or private land, is to understand that once a buck is located, it’s there for a reason.

“They’re going to spend most of their time where they feel safe,” Thayer said. “If they do get spooked, they run to kind of a backup spot. They run out there, and hang out for a day or two. Then they come back.”

That means the patient hunter, who doesn’t get frustrated and start moving around, can score big.

“You know they’re going to be back there,” Thayer said.

And then it’s all about being on stand when the buck walks by.

“I’m still convinced 95 percent of this is luck,” Barre said. “The other 5 percent is trying to improve your luck.”

Getting in the woods early is a major part of that improvement.