New Orleans quarterback Drew Brees treated young patients to a day of battling speckled trout and redfish rather than life-threatening illnesses.

Julius Gibbs had never caught a fish. Ever. Not even a bream. Neither had Charles Nicholson.But thanks to Drew Brees, those days are over.

The New Orleans Saints All-Pro quarterback hosted 30 seriously ill children to a day of fishing fun during a sun-splashed Sunday in May.

Julius, 12, and Charles, 13, were two of the lucky participants.

After enjoying a luxurious stretch-limo ride to Capt. Andy Mnichowski’s new lodge in Buras, the boys were noticeably wide-eyed and eager for the day’s events to begin. They were upbeat and chatty during a truck ride from the lodge to Venice Marina with their guides for the day, Billy Nicholas and Jason Catchings. Also tagging along was Saints punter Steve Weatherford.

“I couldn’t sleep last night,” Julius said. “I set my alarm for 4:30 this morning, but I woke up at 4 o’clock.”

Charles didn’t quite know what to expect.

“I’m a little nervous,” the Adams Middle School student said. “My first boat trip was on a ferry at the Riverwalk.”

But he donned his life jacket and sat on the aft deck as Catchings backed the 24-foot bay boat into the water. Charles knew this boat trip would be much different than the ferry ride, especially when Nicholas asked him if he wanted to drive as they were exiting the Venice Marina harbor.

The burgeoning angler gratefully accepted the offer, and turned right into Tante Phine Pass. From there, Nicholas directed him into Red Pass, where the opaque brown water of the river was giving way to the sparkly green of the Gulf.

Nicholas, a touring redfish pro from San Marcos, Texas, ordered a quick left at the mouth of the pass, and pulled back on the throttle. A subtle point jutted from the roseau-stacked shoreline, and it held more mullets than the grandstand at Talladega.

But the promise of big catches quickly dwindled, and for the first 15 minutes, the boys wondered if any of their fishing dreams would come true. The school of mullet seemed to attract only gafftops and one lost, undersized redfish.

So Nicholas trolled up to an adjacent point, the other side of which was being fished by Brees and Mnichowski.

On his first cast across the point, Weatherford, a college decathlete, gave his rod an Olympic-strength hookset, and the day’s first real fight was on.

Weatherford lived in Baton Rouge for a decade, but he spent his teen years in Indiana, where, he admitted, the fishing isn’t very good. He had nothing in his past to call on to give him guidance on how to fight a smoking-mad 20-pound bull red.

“The biggest fish I’ve caught before this was 4 pounds,” he said through gritted teeth while a screaming drag gave up a steady stream of PowerPro.

While Weatherford’s fish ran, three or four others chased it, apparently not wanting to miss out on the yummy free vittles being offered. Nicholas and Catchings cast into the fray, and both had fish on that they handed off to Charles and Julius.

The boys’ first fights with legitimate game fish were bare-knuckled brawls that they could never have imagined during the previous sleepless night. The reds were big, mean and mad, and they pulled with strength that had to be felt to be believed.

Weatherford’s form was a far cry from his frame, but since his fish was the first hooked, it was also the first to tire. After repeatedly being dragged to the boat, and several spirited runs away from it, the bull red finally succumbed to the net.

Weatherford was as jubilant as the boys would eventually be. He hoisted his fish in the air and playfully chided Brees as well as Saints left tackle Jammal Brown, who was in an adjacent boat.

While the screech of slipping drags filled the salty air, Weatherford slowly revived his fish, and watched it swim away.

But the champions of this day were Charles and Julius. Like fans at a packed stadium on a cool October evening, Weatherford and the two guides sat back and enjoyed the show. The boys weren’t thinking about hospitals or needles or their medical conditions; all that mattered in that moment was reducing their first fish to possession.

They put their rods, reels and line to the ultimate test, but all held true, almost as if providentially steeled.

Like a lacrosse defenseman, Nicholas swapped sides of the boat with the net, whenever one fish or the other appeared to be giving up the ghost. It was Julius’ bull that first decided it didn’t want to fight anymore, and soon found itself being supported by black webbing.

Everyone on board instantly shared in the elated angler’s contagious smile — except Charles, whose grimace illustrated the delightful strain in his burning biceps. It wouldn’t last long, however. The fish was finished, and Nicholas netted it to join Julius’.

After posing for more pictures than Cindy Crawford, the boys released their fish, and were casting baits in anticipation of the next fight. They caught redfish until their tired arms could take no more punishment.

“We caught a lot more than I thought we would,” Charles said after a short ride back to Venice Marina. “I was surprised we got them in.”

“I know this might sound strange,” Julius said, “but that was the best fishing trip of my life.”

He was reminded that this was the first fishing trip of his life.

“I know,” he said, “that’s why I said it might sound strange.”

Both were appreciative to Brees for giving them the opportunity.

“He’s a very, very nice man,” Julius said.

Through his Brees Dream Foundation, Brees had organized a similar event on a much-smaller scale while he was in San Diego. Then last May, just a few weeks after he signed with the Saints, Brees chartered Mnichowski. The guide and the quarterback formed an instant friendship.

“I expressed to (Mnichowski) that I wanted to do the same thing down here,” Brees said. “I figured we could incorporate the best of what Louisiana offers — which is incredible fishing — with what we do well through the foundation, which is helping those with some special needs.

“(Mnichowski) was very enthusiastic about it, and to be honest, we couldn’t have done all this without him.”

It’s not surprising that the naturally altruistic Brees would choose fishing as the means to entertain these children. Some of the best times of his own childhood, Brees said, were while on the water fishing with one grandfather in Arizona and another in Texas. He also relished occasional trips to Port Aransas, Texas, to fish for trout, reds and drum with an uncle.

“Then I really got into saltwater fishing when I went to San Diego,” he said. “There’s lots of good bay fishing there.”

When Brees signed a six-year, $60 million contract with the Saints after the 2005 season, he simply transferred his new love of saltwater fishing to the Sportsman’s Paradise, and he’s proven as successful with it here as anything he’s done in his football career.

In fact, the day before the Children’s Hospital event, Brees took some of his offensive lineman out on an offshore trip. They hooked three marlin — leadering one — in addition to several wahoo, mahi and tuna.

But that was just a warm-up for the real event of the weekend, which was the trip with the children, many of whom were gravely ill.

“A lot of the kids here today are cancer patients,” said Gina Lorio, special events manager for Children’s Hospital. “Some are in remission, but others are still sick.”

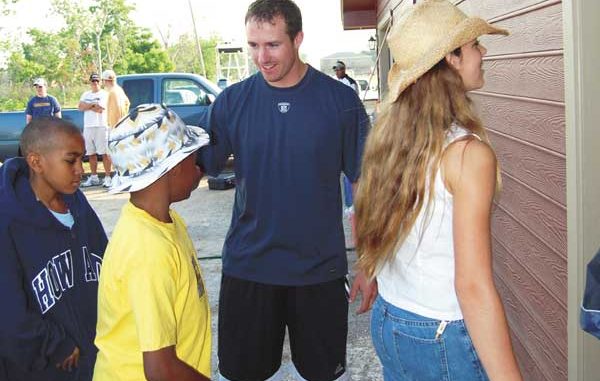

When they arrived in the morning, Brees greeted each one personally, which meant a tremendous amount, Lorio said.

“He’s the ultimate team player,” she said. “To have him here in New Orleans and to see what he’s done with Children’s Hospital, it’s just incredible. When these kids heard his name, they all wanted to come.”

Children’s Hospital is one of Brees’ favorite charities, and his presence on the Saints has greatly benefited the medical center. During the season, FedEx donated a total of $35,000 to Children’s after Brees twice won FedEx Air Player of the Week honors and then ultimately won the FedEx Air Player of the Year award.

But Brees also dug into his own pocket to completely refurbish the hospital’s rehabilitation van, which staff uses to take patients on outings.

“He paid to get it all wrapped, so now when people see us going 20 m.p.h. under the speed limit, they understand. They don’t get mad at us,” Lorio joked.

Charles and Julius will certainly be grateful for any trip they get to take on the rehabilitation van, but none will measure up to driving a high-speed bay boat to the fish-rich grounds at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

They didn’t ride in a van, but several times it felt like they were hooked to one.