Nature has taken many years to delicately handcraft the perfect Sportsman’s Paradise.

When many Americans think of Louisiana today, they visualize a swampy morass covered in cypress trees and Spanish moss.Actually, Louisiana has a wide variety of landforms. From the piney hills to the coastal marshes and from the Atchafalaya’s hardwood forests to the open southwestern prairies, Louisiana is an ecological paradise.

While the entire state was created by sediments filling in the Gulf of Mexico, these various landforms were created by a variety of geologic forces.

Land takes shape

Since Louisiana was created by rivers forming deltas and coastal marshes, it has continually expanded from north to south. In geologic time, then, the land is oldest in North Louisiana and gets younger as you travel south. Over millions of years, the tremendous weight of all the sediments compressed some of the sediment layers into sedimentary rock, particularly sandstone. In fact, all of the rock formed in Louisiana was created this way. The oldest exposed rocks are 60-million-year-old shale located around Caddo Lake. In some parts of Louisiana, petrified palm wood can also be found.

Most of Louisiana’s rock is found in the hills, which were formed after the Gulf Coastal Plain took shape. These hills were created when geologic forces such as magma or the shifting and colliding of the continents forced the land upward. Rain and streams then eroded away the softer elevated material, and the harder areas were left exposed as hills and ridges.

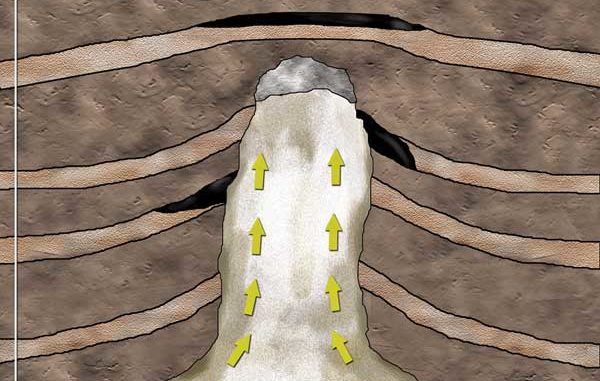

Salt domes are a reminder of the ancient Gulf of Mexico that once covered all of Louisiana. The Gulf has fluctuated greatly over millions of years, and sometimes parts of it dried up, leaving a layer of salt and other minerals on the exposed ocean floor. This salt later was covered up by sediments, and today is about 10 miles beneath the ground surface. The incredible weight of so much material exerted a downward pressure and in some places squeezed the salt upward like toothpaste into tall vertical columns known as salt domes.

Salt domes in South Louisiana stick up out of the low-lying coastal marshes, and appear to be wooded hills about two miles in diameter. Because of this unique feature, they often are called islands. Some of the most famous salt domes are the Five Islands located between New Iberia and Morgan City. From north to south, they are Jefferson Island, Avery Island, Weeks Island, Cote Blanche and Belle Isle.

In North Louisiana, salt domes do not protrude above the surface but instead are patches of bare open ground where the salt appears as a white, sandy crust. Drake’s Salt Works near Goldonna, in Natchitoches Parish, is a good example of a North Louisiana salt dome.

Earthquakes are generally associated with the western United States, but Louisiana actually is crisscrossed by many fault lines and frequently experiences mild tremors. These faults are created by the incredibly heavy sediments that built up Louisiana.

Since the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico is much lower than the land, there is a tendency for the land to break off and slide downward toward the Gulf. These weak areas are called faults, and they are quite common in South Louisiana, where they usually run in an east-west direction parallel to the Gulf Coast.

One visible fault is in Baton Rouge. If you drive north on College Drive from I-20, you will soon go up a slight 20-foot rise. This “ridge” actually is a fault line where the land beneath Baton Rouge is collapsing and slowly sinking toward the Gulf.

Normally, ground movement along faults is very slow, and we do not notice it. But if the land gives way suddenly, the result is an earthquake. While most Louisiana earthquakes are so small they are not noticed, occasionally they are strong enough to be felt. Shreveport, Lafayette, Baton Rouge, Denham Springs, Opelousas and New Orleans have all experienced earthquakes.

Louisiana has also been affected by large earthquakes that occurred elsewhere. A powerful 1812 earthquake near New Madrid, Missouri, caused buildings to sway in New Orleans, and a 1964 Alaskan earthquake caused tidal surges on the Louisiana Gulf Coast. Experts have predicted when the New Madrid fault has its next major quake, buildings may be damaged as far south as Monroe.

Natural regions

Natural regions are determined by climate, soil, vegetation and relief (the difference in elevation between the highest and lowest points of an area). Louisiana has three natural regions — coastal marshes, floodplains and uplands.

Coastal marshes, which were discussed in Part I, form most of the Louisiana Gulf Coast. This low, wet area was created by rivers depositing sediments into the Gulf and slowly building up the land.

Marsh vegetation includes such grasses as bluestem, broom sedge, water grass and switchgrass. Generally, trees are not found in the coastal marsh, except live oaks do grow on cheniers. The marsh is incredibly rich in fish, shellfish, ducks and geese, and deer, rabbits and other game can be found on cheniers and natural levees.

Floodplains are the low, flat valleys through which rivers flow, and they include swamps, sloughs, bayous and lakes. Deciduous forests containing cypress, oak, hickory, pecan, magnolia, tupelo gum, cottonwood and canebrakes dominate this region.

Louisiana’s large hardwood forests and canebrakes are found in the Tensas and Atchafalaya floodplains. Deer, bear, turkey and innumerable other animals call the floodplains home. This region also boasts some of Louisiana’s richest agricultural land.

Uplands are those parts of Louisiana with the highest elevation. The largest upland area is the so-called Piney Hills, a V-shaped region between the Red and Ouachita rivers in North Louisiana. The Piney Hills include Driskill Mountain, a 535-foot hill in Bienville Parish that is the highest point in Louisiana.

Other Upland areas include the Kisatchie Hills in Natchitoches and Vernon parishes, the Dolet (DOE-let) Hills in DeSoto Parish and much of the Florida Parishes. Upland regions contain some hardwood deciduous trees, but they are mostly covered in shortleaf and longleaf pine.

Today, the Uplands provide some of the state’s best deer and turkey hunting because timber management practices create diverse habitat that benefit such game animals.

Ancient river terraces are also part of the Uplands, but they are often incorrectly referred to as “hills” because they are higher than the surrounding land. Terraces include Sicily Island, the Bastrop Hills, Macon Ridge, the pine flatwoods of west-central Louisiana and Florida Parishes, and a rugged area in West Feliciana Parish known as the Tunica Hills. Because terraces do not flood, they support a variety of trees, including oak, sweet gum, tupelo gum, magnolia, hickory, cottonwood, sycamore and cypress.

Prairies — flat, grassy plains that have few trees — can be found in all three natural regions. When the French came here in 1699, approximately one-third of the state was covered in prairies. They were particularly common in Southwest Louisiana between modern-day Lake Charles and Opelousas, and large herds of buffalo roamed some of them. Today, most of Louisiana’s prairies have been destroyed by agriculture and urban development.

Rivers and bayous

Louisiana is crisscrossed with hundreds of miles of rivers and bayous. “Bayou” comes from the Choctaw Indian word “bayuk,” meaning a small, slow-moving stream, but there are no set rules to determine which name is used for a body of water. For example, Dugdemona in North Louisiana is labeled a river on maps, but some highway bridges call it a bayou. Because the French tended to prefer the term bayou, many more streams in South Louisiana carry that designation than in the northern part of the state.

Some of Louisiana’s streams are in pristine condition, and 48 have been designated Natural and Scenic Rivers to protect them from being destroyed or polluted. Saline Bayou in North Louisiana and the Tchefuncte River in the Florida Parishes are two Scenic Rivers that provide excellent opportunities for hunting, fishing, and canoeing.

If Louisiana were a person, the Mississippi River would be the main artery. The Mississippi (an Algonquian Indian word meaning “large river”) is the largest river in the United States and the fourth largest in the world. Beginning in Minnesota, it flows 2,350 miles to the Gulf of Mexico, and drains 32 states (about 41 percent of the nation) and two Canadian provinces.

More water flows down the Mississippi than all of Europe’s major rivers combined. It carries an incredible 375 billion gallons a day through Louisiana, and could fill the Louisiana Superdome in about 30 seconds.

The Mississippi is also the deepest river in the state — at New Orleans it is 2,200 feet (nearly a half mile) wide and 191 feet deep. A building nearly 20 stories tall could be dropped into the river there, and it would completely disappear.

The Red River is Louisiana’s second largest river. It begins in New Mexico, flows through Northwest Louisiana, and enters the Mississippi River near Simmesport. The reddish sediment it carries gives the river its name.

The Red River is unique in two ways. One is its salt content. The river flows over an underground salt dome on the Texas-Oklahoma border, and picks up just enough salt to give the water a high salt content. Since some crops cannot tolerate salt, farmers in the past have been reluctant to use Red River water for irrigation. The Red also is the only major river in Louisiana that once had white-water rapids. In ancient times, the river cut through a sandstone formation at modern-day Alexandria. This created a series of white-water rapids, and is why the French named the parish Rapides (French for “rapids”).

The wild, untamed Atchafalaya River is the largest distributary of the Mississippi River. Exiting the Mississippi near Simmesport, it flows 125 miles to enter the Gulf of Mexico at Morgan City. The Atchafalaya basin is truly a sportsman’s paradise, and it is the largest swamp wilderness in the United States. One-half of all the nation’s migratory birds winter there, and the basin supplies the United States with 23 million pounds of crawfish a year. It also is home to 200 bird species, and is the largest refuge of the Louisiana black bear.

Controlling the rivers

Our many rivers are a mixed blessing. Their sediments created Louisiana, and the rivers are very important to the economy and for recreation, but their frequent floods have also devastated the state. Because of this, tremendous amounts of money and labor have been spent to control our rivers.

The first flood-control levees were built by the French in the 1700s, but the levee system we have today is a result of the great Mississippi River flood of 1927. That flood covered one-fourth of the state in water for several months. Afterward, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began building an elaborate levee system to protect Louisiana and other states within the Mississippi Valley.

Today, the levee system helps protect us from flooding, but it has exacerbated the coastal erosion problem. Now that they are contained in a narrow channel, major rivers can no longer overflow their natural levees during floods, and sediments are no longer being deposited to maintain the coastal marshes.

Dam-like structures have also been constructed along the Mississippi River to allow some water to be drained away during floods to take pressure off the levees. These structures also keep the river within its present channel and prevent it from changing course down distributaries.

The Atchafalaya River is actually a new river that is constantly changing. For 2,000 years, it was an insignificant distributary of the Mississippi River because a large logjam blocked the head of the Atchafalaya and acted as a dam to prevent the Mississippi from flowing completely down it.

The entire Atchafalaya ecosystem began to change after the federal government decided in 1831 to dig a connecting channel between the Mississippi and Red rivers to give steamboats easier access to the Red. Famed steamboat captain Henry Miller Shreve undertook the project and cut a channel through Tumbull’s Bend. This new channel eventually became Old River, and it allowed more of the Mississippi’s water to flow into the Atchafalaya.

A few years later, the logjam was cleared away, and all of the Red River’s water began flowing down the Atchafalaya instead of into the Mississippi. Since the Red carries 10 times more sediments than the Mississippi, the consequences were immediate and dramatic.

The Atchafalaya was suddenly transformed from a small stream into a large river, and the increased sediments began creating natural levees where none previously existed. Swamps and lakes were filled in with sediments, and a hardwood forest grew up where previously there was only water. Six Mile Lake completely disappeared, as did most of Grand Lake.

This process has continued ever since. So much sediment was brought down the Atchafalaya during the 1973 flood that a delta was created in Grand Lake. It is estimated that sediments will completely fill in the Atchafalaya Bay within the next 50 years, and it will become a coastal marsh.

Today, the Atchafalaya’s route to the Gulf is 190 miles shorter and 12 feet lower than the Mississippi’s, and there is a danger the Mississippi River will change course to take this easier path. If that happens, it is estimated almost half of the Mississippi’s water would go down the new channel. The consequences would be devastating.

Morgan City and other towns along the Atchafalaya would be flooded, and the economies of New Orleans and Baton Rouge would be ruined. Those cities depend greatly on trade, but if the Atchafalaya siphons off its water, the lower Mississippi River would become too shallow for ocean-going vessels to navigate.

With the loss of so much water, the Mississippi’s current would also slow down, and salt water from the Gulf would intrude far upstream. The drinking water of Baton Rouge and New Orleans would be ruined, and the salt water would kill all of the vegetation along the river bank. Without the vegetation to hold the soil in place, erosion would begin, and within a short time, the lower Mississippi River would become a bay of the Gulf of Mexico.

To prevent such a disaster, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Old River Control Structure at the head of the Atchafalaya River near Simmesport. Completed in the 1960s, this concrete structure is 60 feet high and 1,500 feet wide, and has a lock system that allows boats to pass through. The Old River Control Structure allows about 25 percent of the Mississippi’s water and all of the Red River’s water to flow into the Atchafalaya. That means today the Atchafalaya is composed of about two-thirds Mississippi River water and one-third Red River water.

So far the Old River Control Structure has been successful in keeping the Mississippi from changing course down the Atchafalaya. The dam almost collapsed during the 1973 flood, but emergency repairs stabilized it and averted a disaster. A new structure was completed in 1987, but there may be no stopping Mother Nature. In time, the Mississippi might very well break through the dam and dramatically alter the face of Louisiana.

The Bonnet Carre and Morganza Spillways are other control structures that were erected on the Mississippi River in 1931.

The Bonnet Carre Spillway was constructed upstream from New Orleans on the river’s east bank. During floods, about 25 percent of the Mississippi’s water can be diverted through the spillway into Lake Pontchartrain to help relieve pressure on the New Orleans levee system.

The Morganza Control Structure is located on the west bank of the Mississippi River upstream from Baton Rouge. During floods, it can protect the levee system by diverting water out of the Mississippi into the Atchafalaya Basin.

Another large river-control project was carried out on the Red River. The Red suffered from many problems over the years. It frequently flooded and was too shallow for commercial barge traffic, and farmers avoided using its water for irrigation because of its high salt content. The murky, sediment-filled water also supported few game fish for recreation.

To improve the river’s economic and recreational potential, the federal government spent $1.9 billion to construct five locks and dams. At the time, the Red River was the largest undammed river in the United States. Completed in 1994, the system was called the J. Bennett Johnston Waterway after Louisiana Sen. J. Bennett Johnston, who sponsored it.

These locks and dams deepened the river to allow barges to reach Shreveport. Flooding was also better controlled, and the water quality improved because the dams slowed the river’s current and allowed both the salt and sediment to settle to the bottom. When the water clarity improved, fish populations exploded.

Today, the Red River is one of the most popular fishing spots in the South, and many farmers are using its water for irrigation.

Lakes

Louisiana is blessed with numerous fresh and saltwater lakes that provide outdoorsmen unlimited opportunities to swim, fish, boat and hunt. But not all lakes are alike. There are, in fact, five types of lakes in Louisiana that were created by different forces.

As seen in Part I, Louisiana’s rivers seek the path of least resistance, and often straighten themselves out by cutting off meanders. When this happens, the ends of the meanders eventually fill in with sediments, forming a crescent or horseshoe-shaped oxbow lake. Oxbow lakes are very common on such rivers as the Mississippi, Red and Ouachita, and they provide some of Louisiana’s finest fishing. Mississippi River oxbows include False River, Lake Yucatan, Lake Bruin and Concordia.

Depression lakes are created when the land gradually subsides along a fault line or sinks quickly during an earthquake. Duck hunting mecca Catahoula Lake in east-central Louisiana is a depression lake. Today, the fault line that created the lake can still be seen in the form of a steep bluff that runs around the western shore.

Most depression lakes are found along the Gulf Coast and include Lake Maurepas, Calcasieu Lake and Lake Pontchartrain. Lake Pontchartrain is also Louisiana’s largest lake. Like most depression lakes, it is quite shallow, covering 635 square miles but having an average depth of only 12 feet.

Raft lakes are found only along the Red River, and were originally formed by the huge logjam called the Great River Raft. The Red River has very steep banks that often slough off during floods, dumping trees and other debris into the river. Hundreds of years ago, this debris grounded in shallow water and formed a logjam. Each year, more logs came down the river, and the logjam began creeping upstream.

When the logjam passed the mouth of a tributary such as Saline Bayou, it acted as a dam and prevented that stream from draining. The bayou then backed up and created lakes when it flooded low-lying areas.

Raft lakes are some of Louisiana’s most beautiful with acres of moss-draped cypress trees and outstanding fishing. They include Lake Bistineau, Black Lake, Saline Lake, Iatt Lake and Nantachie Lake.

By the early 19th century, the Great River Raft stretched nearly 200 river miles above Natchitoches. It was so thick in some places wagons used it to cross the river, and in other places trees grew out of the raft. Witnesses claimed a person could stand on the raft in what appeared to be a small forest and feel the mighty Red River flowing beneath them.

Anxious to make the Red River navigable for steam boats, the federal government contracted Henry Miller Shreve to clear the Great River Raft in the 1830s. Using steam powered snag boats that he personally designed, Shreve completed the task in less than four years. At the time, it was considered one of America’s greatest engineering feats.

When the raft was removed, the Red’s tributaries were able to drain, and the raft lakes disappeared as permanent bodies of water. In the 20th century, however, modern concrete dams were placed on the bayous to reestablish the raft lakes.

As the name implies, coastal lakes are found along the Gulf Coast. They were formed when cheniers slowed the flow of rivers into the Gulf, and lakes built up behind them. Coastal lakes such as White Lake and Grand Lake have brackish water and can support both fresh and saltwater fish.

Reservoirs are manmade lakes, and are mostly found in North Louisiana because the streams found in the Uplands are more easily dammed. These reservoirs help control floods, supply water to cities and provide excellent fishing and boating opportunities.

Reservoirs include Caney Lake, Lake D’Arbonne, Lake Claiborne, Poverty Point and Toledo Bend. Toledo Bend Reservoir is the third-largest manmade lake in the United States, covering 186,000 acres and having 1,200 miles of shoreline. It also has a hydroelectric dam to provide electricity to the region.

Future Louisiana

Louisiana is the product of myriad forces, both natural and manmade. From its watery birth eons ago to its worn and weathered appearance today, the state’s landscape has continually evolved. Even today, natural uplifting by tectonic forces and subsidence from fault activity continue. Rivers still meander across their floodplains cutting new channels and forming oxbow lakes.

But in the last century, man has accelerated these changes. Vast expanses of hardwood forests have given way to cotton, corn and soybeans. Where buffalo once roamed on broad, open prairies there are now endless fields of rice. And numerous small streams that rolled lazily past towering cypress trees for thousands of years are now impounded with concrete dams.

But such changes aren’t necessarily a bad thing. Without the corn and rice fields, Louisiana’s dove, duck and goose hunters would suffer. The small streams that once crisscrossed Louisiana provided limited fishing opportunities, but outdoorsmen by the thousands can now chase monster bass in any number of high-quality lakes. And in North Louisiana, hunters are the first to recognize that the changes brought about by the modern timber industry have made today the “good-ol’ days” in terms of deer and turkey hunting.

The one place where manmade changes pose the greatest threat to Louisiana’s future is the coastal marsh. There, commercial activity and flood-control projects have reversed the natural marsh-building processes. If serious efforts are not soon made to stabilize the marsh and protect its barrier islands, Louisiana might one day disappear beneath the same Gulf of Mexico that spawned it.

Terry L. Jones is a professor of history at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. This article is based on his Louisiana history textbook The Louisiana Journey (Gibbs Smith Publishers, 2007).