On still mornings when the fog is thick enough to cut, you should be working topwaters across Catfish Lake. That’s because big speckled trout are waiting to make your knees weak with crushing strikes.

“The fleas are on the dog, my friend, the fleas are on the dog, but if its fish you’re looking for, the fish are in the fog.”

— Anonymous

I reckon that old poem was written by somebody who knew a thing or two about fishing, because down here in Southeast Louisiana those foggy mornings mean good fishing.

It means the winds are slight to non-existent, and after winter’s long blow you have to take advantage of such mornings.

Of course, fog presents some challenges to anglers because driving to the launch and riding in a boat can be treacherous in low-visibility conditions. But old salts will tell you that if you can safely get on the water on a foggy morning, you’ll catch fish.

That’s especially true if you like working topwater baits.

I recently invited myself aboard Capt. Mike Guidry’s 24-foot Blue Wave Pure Bay for just such a foggy-morning trip out of Golden Meadow.

The drive from Kenner was foggy, but there was enough visibility to make it doable. Even at the launch the fog was thick but not what I’d call terrible.

Guidry said it was safe enough to travel in, so he cranked up the 250-horse Mercury and we headed out toward Catfish Lake.

The short ride snaked through a section of the Texaco Canal system, which is a great place on colder days to toss plastics on the bottom for hungry specks and reds.

Guidry said it’s best to fish the canals like you were bass fishing: Just slowly troll the canals and throw ¼-ounce or even 1/8-ounce jigheadss, working the soft-plastics slow on the bottom.

He uses smaller baits, mostly H&H beetles, and lighter jigs, and slows down his retrieve in the colder months.

“There’s a lot of debris on the bottom in these canals, and a lot of oyster reefs,” Guidry said. “They definitely hold fish in the colder months, but be prepared to hang up on the bottom because of all the snags,” he said.

But we wouldn’t be fishing the canals that morning. We had other plans for the day.

Topwater bait plans.

“I don’t usually get to fish topwater baits because they’re just too dangerous to allow inexperienced clients to whirl them around in a crowded boat. That’d be a quick disaster,” Guidry said. “So we fish a lot of soft plastics and live minnows this time of year, on spinning reels.

“But February and March are my favorite times of the year to fish this Catfish Lake area and the sulfur mine area with a topwater bait on a baitcasting reel.”

But timing is the key to the entire deal, he said.

The key to success — and I can’t stress this enough — is after a front blows through, wait until the winds switch around and blow from the south,” Guidry said. “That brings good, warmer and saltier water back into the area, and the trout will spread out over the shallower flats and reefs and feed.

“That’s when you go fish with topwater baits.”

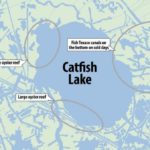

Catfish Lake itself is about 4 square miles of brackish water. It averages 3 to 5 feet deep, but a deeper channel that is about 8 feet deep crosses it from east to west, and in colder weather fish often huddle there on the bottom.

The lake is fed by Grand Bayou and Bayou Monnaie, and it is attached to the Texaco Canal system and several other smaller canals and bayous.

It’s like an octopus, with legs going out in every direction.

That means a lot of water flows through it, and where water flows it carries bait along with it.

Add to its attraction the fact that numerous oil and gas companies have dotted the area with wells over the past five or six decades — leaving behind large shell pads that became perpetual fish habitats — and the several large oyster reefs along the western side of the lake that attract fish like dogs to bacon.

That combination makes Catfish Lake and its nearby cousin, the sulfur mine, prime locations from late fall through spring.

We entered Catfish Lake from the east side, and Guidry’s plan was to fish the west side, where he’d caught some fish the week before.

The fog hung heavily over the surface, which forced Guidry to reduce speed and watch ahead intently and listen carefully. While we had some visibility as long as we proceeded cautiously, the greater danger was posed by other boaters speeding through the fog.

The lesson being, slow down in low-visibility conditions.

Guidry slowed down even more when we got closer to the bank. We couldn’t actually see it in the fog, but he recognized some wellheads and knew we were close enough to kill the outboard and drift or troll from there.

From long experience on the tournament trail, he knows how quickly big fish spook in shallow water, and he insists most anglers get much too close to their fishing spot before killing their outboards.

“I sneak in from 50 to 100 yards away,” he explained. “If I’m going to fish a point, I’ll start trolling anywhere from 50 to as much as 100 yards before I get to that point — especially when I’m using topwater baits, because I’m hunting for bigger fish.

“Big fish and big bucks have a lot in common: They live long enough to get big because they are very wary, and they’ll spook if you are noisy. We can be noisy and still catch smaller fish, but if you want the bigger fish, then move slower and quieter.”

Once he deployed the i-Pilot trolling motor, we tried our topwater baits on both sides and in front of the boat. I was throwing a bone/chartreuse MirrOlure She Dog, while Guidry had on a bright chartreuse Rapala Skitterwalk.

I had the first blow-up, but didn’t manage to hook the wily critter.

A few minutes later I caught one, but it was only about 13 inches long.

We worked the area over thoroughly because it was a known to produce some nice trout, but on this morning they just weren’t paying much attention to our surface baits.

We finally got fairly close to another boat in the fog, hearing them long before seeing them.

We watched them drag several specks over the gunnel using soft plastics retrieved slowly.

Guidry recognized the captain as another guide, and he told us they were having success on the smoke-colored H&H beetles on 1/8- or ¼-ounce jigs.

We continued working the area over with topwaters for another 20 minutes or so, but we had only a few half-hearted swipes by smaller trout.

Guidry decided to pull up and move to a different section of the lake.

Fog still reduced visibility, but it never really socked us in. Guidry brought us to a section of the lake where a huge oyster reef covered the bottom.

“The whole circumference of Catfish Lake is fishable,” Guidry said, “because it is all good shoreline, with lots of cuts and points and pockets, and all of it holds fish.

“I like to come out here and just troll the bank for redfish, tossing gold spoons or beetle spins. You can often see them cruising along the bank and you sight cast to them.”

Betting those fish to swallow a bite is pretty basic.

“Try to toss your bait at least 4 or 5 feet ahead of them so you don’t spook them, and reel slowly so you give them a chance to see it,” Guidry said. “It’s a thrill to actually watch them pounce on your bait.”

The guide said to look for points with decent water and some current moving around it, and troll or drift that area while casting your baits, whether topwaters, soft plastics or spoons and spinners, because specks and reds hang in the current.

Guidry also said there are two big areas of shoreline in Catfish Lake with a heavy oyster bottoms where he particularly likes to fish, and both areas produce trout and reds.

“The west side of the lake and the south-southwest side have a good oyster bottom,” he explained.

The key to success is not heading straight for the bank.

“The mistake many people make is they try to fish too close to the bank,” Guidy said. “These reefs have been here for years, but over time the land eroded and the shoreline retreated. But the reefs didn’t move. So the real bottom structure is a good 30 to 50 feet off the bank. We’ll sneak in slow and quiet and throw our topwater baits and see if we get some takers,” he said.

After just a few casts we started getting some good swats at our baits.

At first the fish would pop at topwaters, sometimes knocking them up in the air, somehow without getting hooked. We figured they were small trout with ambitious appetites.

After half a dozen such swats, Guidry had a big trout inhale his bait. And then another.

I also got into some good action, but he was catching three to my one. Maybe it was because his Skitterwalk was a much brighter chartreuse than mine, or maybe he caught more because he had the better position on the bow of the boat.

Or maybe because he’s just a better fisherman.

But there was plenty of action for both of us, and these were very nice-sized trout.

We got off of one point and hit a virtual bonanza of hefty specks that slam-dunked our surface baits, keeping our rods bent and our faces grinning.

When that action played out, we moved on to troll a different part of big reef.

The fog not only didn’t lift as the morning wore on, it actually became thicker. However, Guidry wanted to try one more spot before we headed to the dock, so we approached it with his usual ease and tossed our same topwater baits.

This time we had lots of blow ups, but no hook ups. After a dozen such frustrations, I switched rods and tossed a single purple/chartreuse H&H beetle on a ¼-ounce jig, and a nice trout immediately inhaled it.

I did it again and got the same result, and a dozen or so more times after that — all very respectable trout.

Guidry kept trying that topwater bait, but he finally reluctantly put it down to join the jig-generated fray.

We added more nice specks to the box until the action petered out, and we headed home the same way we headed out: in the fog.

It proved to me the old adage is true,

The fleas are on the dog, my friend, the fleas are on the dog, but if its fish you’re looking for, the fish are in the fog.

Editor’s note: Capt. Mike “Rippin Lip” Guidry can be reached at 985-637-4292.