Winter fronts might discourage some, but this Prairieville angler heads to Pointe-Aux-Chenes’ Sulphur Mine for consistent action.

A stiff north wind blew for five or six days before it shifted to the northeast and settled down to 10 to 15 knots.

The forecast for the Friday trip was for the wind to crank back up, blasting the coast at 15 to 20 knots.

While most anglers would have called everything off, Leonard Meaux didn’t seem phased.“I don’t ever pay attention to that,” the Prairieville angler said. “When I have a day off, I’m going fishing.”

I couldn’t believe it. I was going to be fishing in the marsh with winds blowing upwards of 25 m.p.h.

That’ll make for a great day, I thought.

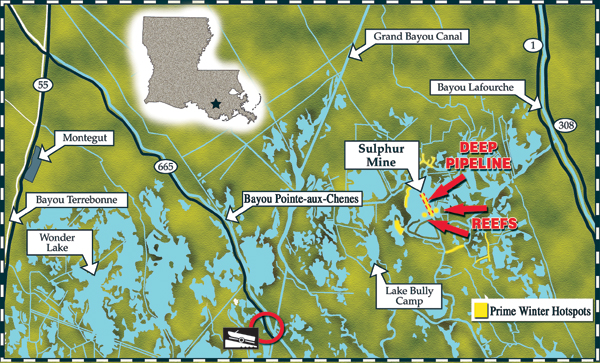

But as the sun peaked over the horizon, we were launching the boat and gearing up for a cold five-mile run to the nearby Sulphur Mine in Pointe-Aux-Chenes Wildlife Management Area.

When we broke out of the marsh into the wide-open waters of the mine, the breeze buffeted the boat. There already was a hard chop on the water, but the wind actually wasn’t that bad.

We streaked across the bay in Meaux’s bass boat, and set up for our first drift.

Live minnows and dead shrimp were stored in the boat, but Meaux didn’t bother with them.

“I always get (live) bait just in case, for emergencies,” he said. “But I’d rather use artificials.

“You don’t have all that mess.”

While I rigged up a cork, Meaux already had his tight-lined bait in the water.

“I hate using corks,” he explained.

Paul Harris, a regular fishing buddy of Meaux’s who joined us for the day, followed Meaux’s lead.

I had decided the night before that I was going to swallow my pride and use a cork.

Even worse, I was going to forego my baitcasting tackle and sink to the use of a spinning rig — something that’s akin to using a Snoopy pole in my book.

But there’s no doubting that spinning tackle is easier to use when the wind is blowing, so I took the abuse from Meaux and Harris.

Within a few casts, my suspended plastic Bass Assassin drew first blood, redeeming me somewhat.

The trout was a nice keeper, and it was soon cooling in the ice chest. It wasn’t long before it was joined by one of its brethren.

Soon, Meaux was grumbling that he might have to dig out his bag of corks.

But it was Harris who first gave in.

After I continued to pull trout after trout to the boat, Meaux finally caved and tied on a cork.

But he would only throw it a few casts.

“I’ll wait until you catch a few,” he would say.

The fish were scattered, but the action was steady.

Although it was still a little early for big concentrations of trout to be in the mine, Meaux said all it would take would be the first bitter cold front to move through.

“It hasn’t gotten cold yet,” he said. “They really get in there when it gets cold — bone-chilling cold.”

That’s when the fish move in and gang up in the deepest waters they can find, seeking warmth from the depths.

However, trout also will sometimes relate to contours on the bottom.

“You fish the ridges and deep spots,” Meaux said.

That’s when the competition for trout gets fierce.

“There’ll be 150, 200 boats in here,” Meaux said.

There are only a few deep holes, but Meaux said the regulars sort of share their fortunes.

“It’s easier to find fish because people will bunch up when someone starts catching,” he explained. “Most people are pretty good about it.”

Even with the pressure, limits can come easy and quick once a school is found.

“If you can catch five or six, you can usually catch a limit right there,” Meaux said.

Ridges take time to find, but Meaux said there are at least two humps that consistently hold fish.

“There are artificial reefs on either side of the canal running through the mine,” Meaux said. “They’re made of oyster shells.”

The canal runs northwest off of Bayou Boullion, and into the eastern edge of the Bully Camp Oil and Gas Field.

The reefs are on the southeastern corner of the mine, and are marked with PVC pipes.

“There used to be a buoy in the center of the reefs, but it was apparently moved during the storm,” Meaux said.

The buoy now sits just on the outside of the eastern reef.

The canal itself is one of the prime deep-water areas, and provides plenty of fishing area because it cuts right through the open water of the mine.

Depths can reach upwards of 25 feet, and make for a perfect refuge for trout.

That depth is what Meaux looks for, but finding bait is a critical key to success.

The cold weather means there will be little surface activity, so this angler keeps his eyes glued to his depth finder.

“You’ll just see clouds (of bait) on the depth finder,” he said. “When you find that, you need to fish straight down.”

These “clouds” of bait will look somewhat like static on the screen.

Meaux will simply drop his lure down, playing with depths and bumping his bait (either artificial or real) until he finds the magic combination.

When bait isn’t balled up, Meaux continues playing with depth as he fan casts.

“I just throw it out and crawl it back, trying different depths,” he said.

Most of the time, he’s going to find the fish right on the bottom.

But when the winds are howling, fishing the bottom sometimes isn’t an option even with heavy lead heads.

“Sometimes it’s hard to get on the bottom,” he said. “I just throw it out and try different depths.

“Try slow, and I try fast. Change it up until you find what works.”

While he might resort to a cork to fish dead shrimp or plastics, minnows are rarely suspended under foam.

“I always tight-line them — unless someone is wearing them out under a cork,” he said. “Then I’ll put one on.”

He lip-hooks his minnows, working from the bottom up to ensure the little fish can swim as naturally as possible.

“It’s easier to keep them alive that way,” Meaux said.

By 10 a.m., fishing became significantly more difficult because of the increasing wind.

Most of the half dozen boats that had been jostling for position over schools had disappeared.

“After about 11 a.m., there’s nobody out here,” Meaux said. “The wind just gets too bad.”

The trout were still there, but huge swags in our lines meant more missed hook sets.

It was miserable fishing.

Meaux moved to the lee side of the bay, working the shorelines and open water alternately.

“You can catch the trout out in the deeper water, while redfish will be in the shallows,” he said.

He often will begin such wintertime drifts on the northwestern corner of the mine, allowing the wind to push him down the western shoreline.

Amazingly, the water wasn’t chocolate milk, even after so much wind-induced turbulence.

Meaux said he wasn’t surprised.

“It never gets unfishable,” he said. “It gets a little stained, but that’s about it.

“It doesn’t take long to settle down, either.”

But by about 11 a.m., we threw in the towel with about 30 trout cooling in the chest.

“Usually as the day goes on, it gets windier,” Meaux explained. “It’s usually just like this: After 10 or 11 o’clock, it’s time to move.”

But Meaux didn’t head to the landing. Instead, he turned north to the canals just off the mine.

“When it gets too windy, I fish the nearby canals,” Meaux said. “You can always find a high-bank canal to get out of the wind.”

Once in the canal, it was amazingly calm. I went back to fishing my baitcaster, and the wind was almost not a factor.

Meaux focused on the lee bank, but he said that’s just being practical.

“I don’t have to fight the wind,” he said.

What he really prefers to focus his attention on is any sloping bank.

“The redfish will be in those shallows, and the trout will be deep,” he said. “So I get to fish for both.”

But he doesn’t ignore the rest of the canal.

“I fish the middle and the sides — reds on the edges and trout in the middle,” Meaux said.

Although Meaux always begins his canal fishing with artificials, Harris is quick to grab a dead shrimp.

“I’m ready to catch drum,” Harris said with a grin.

The first stretch wasn’t very productive, but Harris set the hook after we moved around a corner.

A beautiful trout, weighing a couple of pounds, had been waiting right where the bank dropped off.

Meaux snatched off his plastic and lip-hooked a minnow onto his jig as we approached a rocky bank.

“I just bounce it down the rocks,” he said. “Something will pick it up.”

Dead shrimp is even easier to fish — you simply toss it out, let the jig settle to the bottom and slowly bump it back.

Meaux cautioned that anglers should be very careful when easing into the canals north of the mine.

“A lot of those canals are real shallow,” he said.

After landing only a couple of fish in the northern canals, Meaux called for lines to be hauled in, and turned south to the canals on that end of the mine.

“Any drain you can find will hold fish,” he said.

He made a short run across the bay.

Drain after drain was bone dry, the days of consistent northerly winds having emptied all but the deepest trenasses and ponds.

Finally, Meaux spotted a drain through which the wind was pushing water.

Harris immediately put a shrimp on the bottom, while I stuck with plastics.

I was determined to gain some of my pride back after the morning of cork fishing.

Meaux worked the boat into position with his trolling motor, and then eased his anchor over the side.

“It just makes it easier to fish,” he said. “You don’t have to fight the boat so everyone can fish.”

It didn’t take long for Harris to snatch back on his rod, landing a drum.

Meaux, who also was tossing market shrimp, was next.

I continued to stick with the plastics, convinced that I would find a willing fish.

The action picked up, with Meaux’s boat positioned between two cuts coming out of a small bayou twisting through the marsh.

The catches seemed to alternate between drum and sheepshead, with an occasional rat red mixed in.

Harris and Meaux were laughing and having a good time catching drum after drum, but I might as well have not been fishing.

Finally, to much wise-cracking, I threw what remained of my pride overboard and grabbed a shrimp.

The effect was almost instantaneous — a drum scooped up the stink bait, and received a hook in the mouth for its effort.

Meaux said the canals average 4 to 5 feet in depth, although there is deeper water.

“The bends are deeper, but I’ve never done much good in the bends,” he said.

Therefore, he picks up the pace when reaching a bend, and then slows back down once he moves back into a straight stretch of bank.

The one potential pitfall of fishing the canals is water clarity.

“The water can get muddy in the canals,” Meaux said.

And while he looks for the cleanest water possible, Meaux will fish stained water if all else fails.

“We’ve caught them in muddy water,” he said.

Meaux also advised that anglers remain in the current as much as possible.

“There are a few dead-ends I like, but mostly I stick with the moving water,” he said.

The strategy worked this day, with countless sheepshead and drum falling to the dead shrimp.

Many were throwbacks, but it didn’t take long to put 15 nice eating-sized drum and a like number of monster sheepshead in the boat.

While many anglers might turn up their noses at drum, Meaux and Harris delight in the fish.

“They’re great on the grill,” Meaux said.

The sheepshead are less favored because they’re difficult to clean, but the anglers still keep some of the big ones.

“I take them to some guys at work,” Meaux said. “They love them.”