Trout and reds bloom in the soil of this annual hotspot.

Spring is finally in full bloom. Winter has released its icy grip for another year, and the birds are back to singing their merry tunes. Bees are buzzing, grass is growing and the gardeners among us are glad to get their fingers down in the soil again. It’s hard not to be happy in the spring.

After this long, cold, gray winter, just the feel of May sunshine can give you a brighter outlook, make you feel more hopeful and spur you sing along with some old Young Rascals songs from the 1960s. “It’s a Beautiful Morning” comes to mind, or maybe a little “Groovin’ on a Sunday Afternoon.”

Like I said, it’s May, and things just seem better.

After I mowed the lawn, dug up the carcasses of some of the dead plants that succumbed to the winter’s freezes and yanked the weeds from around the surviving plants (and actually enjoyed the whole process), I got the urge to do another kind of gardening. There is a downriver garden that blossoms every year at this time, and it draws “gardeners” from all over the region who want to come and pick the flowers.

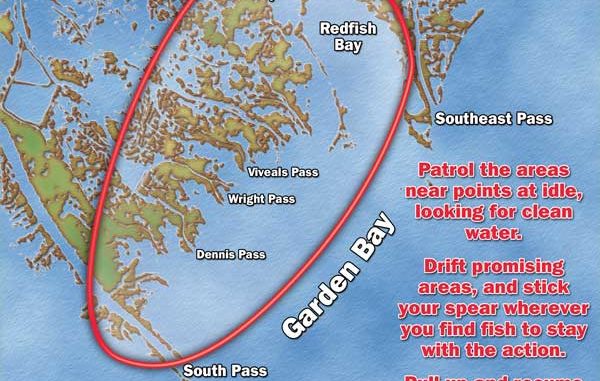

Garden Island Bay

This “garden” is actually a body of water below Venice that stretches between Southeast Pass and South Pass of the Mississippi River, and its blossoms are actually speckled trout and redfish. Garden Island Bay or, as some maps call it, Garden Bay is a sizeable body of water that encompasses Redfish Bay on its north end and numerous passes and branches of the Mississippi all the way down to South Pass. It literally comes alive this time of year with specks and reds like a mountainside blossoms with wildflowers.

I arranged a trip recently with Capt. Shawn Lanier (225-205-5353), who operates out of Venice, to do some gardening in the big bay and see if we could find some flowers. I brought along a good friend, Jerry Dupre. Lanier loaded our gear into his 24-foot Sea Pro and headed us downriver from Venice Marina.

Despite the warming weather, the river temperature is always considerably colder than average due to the cold currents flowing down from upriver, so it’s always wise to bring a jacket for the morning boat ride. The winds were blowing much harder than we’d hoped, and the weather forecast was for a 60-percent chance of rain and thunderstorms, so we knew we’d have to hunt clean water and dodge potential thunder-boomers.

From Head of Passes, Lanier took Pass a Loutre to Dennis Pass, and then turned off at Loomis Pass to the big water of Garden Island Bay. Dennis Pass would have taken us to the same body of water, only farther south than we wanted to start our hunt.

Lanier said the whole area is in its prime this month, as big spawning trout take up residence there and huge redfish prowl the shorelines.

X marks the spot?

Lanier says you really can’t mark a few X’s on a map and just go fish them in this area.

“There are just too many variables downriver,” he said. “The conditions change so rapidly, a point might be hot today and cold tomorrow. It could go from red hot to ice cold in a matter of hours as the conditions change. We’re in wide-open spaces down here, and everything is so susceptible to any fluctuation in the winds, and everything depends on the winds and the tide.

“If the winds lay down for a day or two, good, clean Gulf water will show up visibly, and that water will be chock full of bait and specks and reds. But the winds seldom lay calm for that long, and that’s why you have to hunt. Probably the most important thing you’re looking for down here is clean water. By that, I mean water that is cleaner than the muddy river water. It won’t usually be crystal clear, but it’ll have some clarity or visibility to it so the fish can at least see your bait.

“The problem is, the cleaner salt water from the Gulf is heavier than the murky fresh water from the river, so the lighter river water will often cover the whole surface of the bay and from our viewpoint it all looks dirty, even though some good, clean saltwater is hiding just below the surface.

“The anglers job is to discover where the good water is hiding, and there’s several ways to do that: 1) Look for obvious lines of demarcation, like minor rip lines, where greener water butts up against the river water. That lets you know there’s good water present, and any nearby points are good places to try. 2) Look for birds, which are obvious giveaways that bait is present. 3) Observe your prop wash as you idle through the area. You’re looking for any sign of green water as the suction of the prop pulls water from the bottom to the surface. If you see green water, rolling up behind the boat, you’re in fishable territory. 4) Look for signs of bait in the water. It’s sometimes very obvious — shrimp are jumping out of the water and trout are slamming them from below, or baitfish are running and predators are splashing the surface after them. I love to see that! But other times it’s less obvious and you have to look closely for the little tell-tale signs on the surface.

“That’s why you can’t just mark a few X’s on a map and say fish these spots, because out here that just doesn’t work. In this area the good spots change from day to day and hour to hour as the conditions change. You’ll have to look and hunt each trip you make, but persistence will pay off.”

Lanier pointed to an area on the surface where the cloudy water had some noticeable streaks of a lighter color running through it. I wouldn’t call it green water, but the difference in color was obvious.

“We’ve found some good water,” he said, and confirmed the find by pointing at the prop wash. He cut the outboard and let the boat drift a bit, while we took out our gardening tools and started working the soil.

Lanier’s tactic is to drift as much as possible and to use the trolling motor only when necessary. When the fish start hitting, he puts the Power Pole down and tries to stay with the action.

“The water is shallow and sound travels, so I avoid using the trolling motor if I can. Big trout tend to be nervous, and if that’s your target, you want to eliminate any unnecessary sound,” he said.

Lanier says topwater baits can be very effective right now around the points, and along coves, beaches and canes.

“Both trout and reds will smash topwater baits out here, and few things match that kind of thrill in coastal fishing,” he said.

But the choppy conditions that morning just weren’t conducive to topwater baits, so Lanier and Dupre tossed soft plastics under corks while I opted to throw a gold weedless spoon.

We were in an area of broken canes, and Lanier said a lot of stubble remained just below the surface, so I figured it’d be a likely place to find some reds.

I was right.

The reds were there, and they were hungry. But the bronze beasts ignored my spoon and attacked the soft plastics. Both Shawn and Jerry got solid strikes, and each time they landed a fish, I threw my spoon into the hot zone — to no avail. Since even I am smart enough to throw the fish what they want, I switched rigs so I could join the action.

We landed several nice redfish and a couple of others managed to shake our hooks before the action died out and Lanier pulled up the Power Pole to resume our drift. The next half hour was slow and steady tossing and working our popping corks, looking for more action.

We knew we were in a section of good water so we didn’t want to abandon the area altogether to start exploring all over again, but we wound up not having to make that decision on our own. We got some help from the weather. All morning we were dealing with some light sprinkles of rain — not constant or heavy enough to make us put on rain suits, but enough to keep us watching the sky. There had also been some not-too-distant rumbling and dark thunder clouds off to the side, but sudden wind gusts and a rapid fall in temperature signaled that the storm was coming our way.

Just when the fish started to bite again, a bolt of lightning struck near enough to get us scrambling. In less than a minute, we were enveloped in clouds and pounded by stinging, heavy rain. Lanier cranked up the boat, and we roared toward the Apache Oil Camp to find refuge from the weather.

Shortly after we arrived, another charter captain and his crew pulled in to hide from the thunderstorms as well. Two full hours later, we got enough of a break in the weather to head out again.

After a brief search, Lanier found some promising-looking water, and we started casting our baits in all directions. Lanier and Dupre were tossing Tsunamis in green/white under corks while I tossed a chartreuse grub, which the fish ignored. But the Tsunamis got pounded by some nice-sized specks.

I switched colors, and tried opening night, purple/white and then copper, all of which the trout disregarded. I was feeling pretty dejected when Lanier pointed out a slight difference in our corks. I was using a relatively standard popping cork — the ones with the wire through them and the weights on the bottom end (I especially like the ones with the titanium wire that doesn’t get bent). But my fishing partners’ corks not only had a wire through them, they had a small propeller-looking apparatus just under the cork.

I thought the propeller looked goofy, and in fact I noticed it tended to tangle with their leader line when they tossed it. But they out-caught me three to one with the prop rig. I tossed my baits in the same spots and got ignored, but their baits got inhaled.

Could some other factors have also made a difference? I wasn’t fishing with a Tsunami lure, so does their internal weight make it work drastically different from a standard jighead bait? What about color? Does a bait’s color make that much of a difference? Are fish really that perceptive of subtle differences in color, from underwater, and cloudy underwater at that? And does a goofy-looking propeller on the cork make that much of a difference?

“Sometimes it does,” Lanier said with a smile, as he reeled in another trout.

Capt. Shawn Lanier can be reached at (225) 205-5353.