Bayou Corne is filled with sac-a-lait, and this expert shares how he fills his ice chest — every trip.

Oh yeah! I passed Jambalaya Lane, turned down Gumbo Lane, passed Crawfish Stew Lane and hung a left on Sauce Piquant Lane. How could this be wrong?

Only in South Louisiana!

Great fishing and great food, all in the same place.

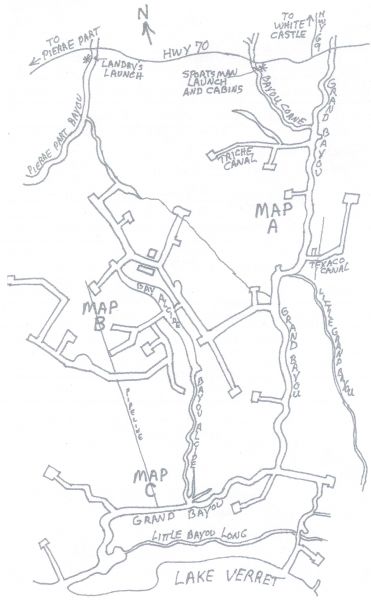

The place was Bayou Corne, the tiny settlement located where Louisiana Highway 70 crosses the bayou of the same name. Smaller than the nearest town of Pierre Part, Bayou Corne is famous for its crappie fishing, known locally as sac-a-lait and in North Louisiana as white perch.

Showing me around would be Jim Looney, a 69-year-old fuel and lubricants salesman. In spite of holding a full-time job, he fishes every day during the daylight savings months and every weekend the rest of the year.

“I tried retiring for eight months,” Looney said. “Boy, you sure get out of the loop fast. You know what they say, ‘retire and die.’”

I had high expectations, in spite of the threatening weather. The Weather Channel showed bands of pure ugly streaming from the southwest to the northeast. It was moving our way.

Still, I thought that we could squeeze in a trip.

It’s November, and it’s cool.

“Prime time for sac-a-lait fishing is when you got to keep your insulated coveralls on all day,” Looney said. “Sac-a-lait love that cool weather. It starts in November and goes until mid-February, when it gets too cold — probably more for the fisherman than the fish. But the fish do get real sluggish.

“When it gets real cold, the north wind is blowing and the water is streaming out under the bridge, the fishing is good under the Highway 70 bridge over Bayou Corne. You have to fish tight-line (no cork) and twitch a jig real slow along the bridge. All you feel is a little bump, and you got to set the hook right away or they will spit it out.”

It takes a few months for the fish to become active again, he said.

“It picks up again in April and into May when they move back into the shallows,” Looney said. “The bite starts first in the deeper waters of Grand Bayou, and then later moves into shallow oil-field canals like those of Bay Alcide.

“It never really gets too hot, but prime time is when it is cooler.”

The entire area we were to fish was one vast cypress swamp. Even under the forbiddingly leaden skies and at a drab time of year, it was picturesque. The snaggly cypress trees were festooned with beards of gray Spanish moss. Tree trunks were all gray and brown, and the cypress needles were brown. Maple tree leaves were mostly brown, with a few remnant splashes of yellow and red colors.

Looney headed south in Bayou Corne from the Highway 70 bridge. He began fishing before he reached Grand Bayou, the banks of which — as well as its interconnecting canals — we would spend the day fishing.

Nothing set this place apart from any other. Dead treetops sprawled into the water, stumps from the swamp’s old forest poked up here and there, and beds of submerged water weeds were visible beneath the surface, especially near the bank.

Looney explained that it was a spot that produced fish for him before. His fishing tactics here were the same as they would be the rest of the day. Using his trolling motor, he kept his boat just beyond casting distance from the bank.

The boat wasn’t in the brush, with him casting into the bayou’s open waters. Nor was he in the middle of the bayou. Rather, he rode its flanks. Most of his casts were toward the bank, but he not infrequently would cast in all directions.

Catching my surprised look at his casts away from visible cover, he rumbled “fishermen need to understand what is beneath them. There are big grass beds out here.”

Fifty bites and one bream later, he cheerfully noted, “One thing that fishing does teach you is patience. You know they are here, but you can’t get them to bite.”

The next spot didn’t produce a fish. Neither did the following several stops in Grand Bayou. He was getting lots of small bumps on his jig, but no hook-ups.

“We’ll get them,” was his only comment about the slow bite. “They’re just tapping, just not aggressive — yet.”

Casts were retrieved in long twitches, three or four of them; then the lure was paused. The pattern was repeated over and over: twitch, twitch, twitch, twitch — pause.

The bites invariably came during the pause.

And they were bream, all of them. Nice big bluegills. While their spawning colors had long faded with the onset of fall, they were still fine big bulls.

Finally, at 9 a.m. Looney’s cork eased down slowly beneath the surface. He set the hook and fought the fish in gently. It was a beautiful 1 ½-pound sac-a-lait.

“It’s too bad it’s a big one,” he said in mock complaint. “I like the medium-to-small ones to eat. The meat on the big ones is too thick to cook up right.”

His craggy face was beaming as he held the fish up for examination.

With the ice broken, the sac-a-lait began to come quickly, some spots produced one, others produced six or eight. Mixed in with them were big bluegill bream.

It wasn’t hard to tell the difference in their bite. With bream, the cork would dance tap, tap, tap and then go down hard. Sac-a-lait would bite either by submerging the cork slowly or by picking the bait up and holding it, causing the cork to move once, and tip over on its side.

It was fun and relaxing — watching the cork and interpreting its language.

Obviously, other anglers knew it was prime time as well. Another boat always seemed to be in sight, running the bayous and canals. Noting the noise of the snarling outboards, Looney said it wasn’t really a problem, as long as the boats keep going.

“I like to sneak up to a spot and drop my troll motor well before I get to my spot,” he said. “But passing boats don’t seem to affect (sac-a-lait) too much.

“At least not until you get enough wakes to muddy the water 10 or 12 feet from the bank. Then I have to change my fishing — fish deeper, farther from the bank.”

As the morning wore on and the sac-a-lait began accumulating in his ice chest, a subtle change in Looney’s tactics occurred.

He concentrated less on submerged grass beds and more and more on stumps, treetops and — most particularly — on innocent-looking logs that extended from the bank out into the water. These, he noted, often signal the presence of an invisible-to-the-angler submerged treetop.

Accuracy, he confided, is the name of the game here.

“If I cast 4 feet from the right spot, they won’t come out and get it,” Looney said. “If I cast 1 foot from the spot, they take it.”

His casts now were pinpoint shots to just outside of any visible structure. Still, he hung up and broke off a lot.

“That’s why I make my own jigs rather than buying them,” he grinned.

Bream he took as he went, but when he picked up a sac-a-lait — which he often referred to as “Mr. Sac,” pronounced as “Mister Sock” — he would turn the boat with his trolling motor to work the spot repeatedly, a tactic that he amusingly called “sashaying.”

The hinges on the ice chest were worked regularly, sometimes for a bream and sometimes for Mr. Sac.

The sac-a-lait bite was good, but the bream were really putting on a show. Even the crusty, experienced Looney was impressed.

“You got to fight your way through the bream to get to the sac-a-lait,” he said. “Every cast is a good bite!”

Soon the call of lunch and the groans of the ice chest became hard to ignore. While he stowed his rods and tidied up the boat, it never stopped rocking as one snarling metal-flaked monster after another passed by us.

“I have people say, ‘I can’t fish on weekends. I can’t stand the crowd.’ I don’t let it bother me,” he said philosophically. “Let them enjoy it while I enjoy it.”

Of course, he was going to the landing with a box of fish.