This Southeast Louisiana river is often overlooked by area anglers, but it can provide outstanding sac-a-lait fishing this month.

The anglers shivered as the boat came off plane, evidence that leading edge of a cold front working its way through the state had reached Blind River.

James Simar, decked out in a yellow-and-black jacket and shirt to match his bright yellow Blazer bass boat, popped out from behind the console and headed to the trolling motor.

Caston Milioto began sorting rods on the front deck, looking for his casting rig.

The water was classic for the area — clear, black, swampy.

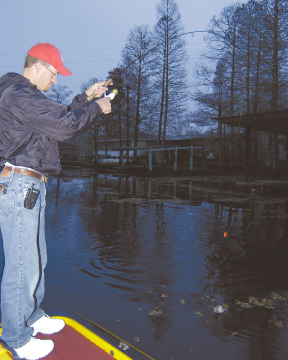

Simar eased the boat into Bayou Conroe, and quickly made the first cast. A fish popped the top of the water to the pleasure of the two Paulina anglers.

“What?” Milioto said, sending out his first morning offering. “They’re here.”

The fishermen looked like tournament anglers out on a scouting trip, and there were some bass rods on the deck.

But Milioto and Simar were casting tube jigs under corks, looking for slab sac-a-lait.

“A buddy of mine caught 32 in here the other day,” Milioto said. “They were slabs.”

The bayou, which runs from Highway 61 near Interstate 10 through the swamps to dump into Blind River, was lined with flooded cypress trees, stumps and grass.

The longtime friends popped their corks, sending the plastic tubes beneath dancing.

“There’s one,” Milioto said, setting the hook.

The cork sank, but almost immediately popped to the top.

“What?” he said. “That was a fish.”

The strike, which barely tickled the cork, energized Simar and Milioto, and they popped their corks and watched for any hint of activity.

With a joyful hoot, Milioto set the hook again. This time the fish didn’t get away.

The anglers harassed each other as the fish struggled, crashing the surface, diving deep, resisting the inevitable trip to the boat.

Once the nice sac-a-lait had been deposited into the livewell, Milioto sent his cork back out.

The pair of anglers fish as much as possible, and they aren’t picky about the species.

They are regulars in the local bass tournaments, but when they hear the crappie are biting in any of the area waterways, they’ll also make meat hauls.

Their favorite technique is to use tubes under corks, letting their lures dangle seductively in front of fish.

Unlike many anglers, Simar and Milioto see no correlation to water depth and water temperature.

Even on the coldest days, when conventional wisdom dictates fishing deep, the two experiment with their corks.

“It’s not really up to us,” Milioto said. “It’s whatever they like.

“If they’re 2 feet deep, we’ll fish 2 feet deep.”

Simar agreed.

“Sometimes they get in the middle of the canal,” he said. “You just have to follow them there.”

The two constantly readjusted their corks, thoroughly working the water column in search of a sweet spot.

They worked one side of the canal’s mouth, and then turned and worked under a light hanging over the water at a camp situated right on the point.

“I don’t know if they have tops down there or not, but I’m going to fish under the lights,” Milioto said.

Soon there were a couple of fish in the boat, but the action wasn’t as frantic as hoped.

“Let’s head to Joe Bourgeois Canal,” Milioto said.

Rods were strapped down, and the big Blazer was boosted onto plane for the short run upriver to this community hole.

Simar rocketed back into the canal, looking for one of their favorite areas — a dead end almost at the end of the canal.

Again, the water was littered with stumps, trees and laydowns.

But the two were careful what structure they targeted.

“We like those big logs with only a few branches or no branches on it,” Milioto said.

The reason was simple.

“It’s easier to work,” he explained. “I’m sure there are fish in those bushy laydowns, but it’s hard to get in there.

“I could get out a long pole and use a weedless hook and get in there, but I’d rather those logs with only a few branches.”

Simar will work the length of such logs, but said there’s one particular part he prefers.

“When you get to the tip of the log, it’s guaranteed to hold a fish,” he said.

The anglers are big believers in lure color.

“We were fishing in a canal one day, and we were catching a few fish. But there were these two old guys who were kicking our butts,” Milioto said.

To make matters worse, the elderly anglers absolutely wouldn’t allow Milioto and Simar to see what they were using.

And then Simar saw a plastic tube floating by. It was dark brown/orange.

“We switched to that, and we started catching them,” Milioto said. “It was the color; that’s all it was.”

So that’s the foundation for all of their sac-a-lait fishing now, but they aren’t afraid to try other colors.

Regardless of what color the fish prefer, however, Simar and Milioto will always tip their jigs with Power Bait Nibbles.

“If I got out here and didn’t have any Nibbles, I’m going home,” Milioto said.

These smelly little chunks don’t necessarily provoke strikes, but they provide additional time for a hookset once a fish does grab a bait.

“It’s not that they make the fish bite, but when they do, they taste something,” Milioto said. “It makes them hold on longer.

“You don’t have to be as quick.”

And that’s important, especially when bites can be very, very subtle.

“A lot of times, the cork will just stand up and not go anywhere,” Simar said. “Sometimes, it floats higher.”

There are times, however, when tubes under corks won’t work, and Simar and Milioto have to tight-line their lures.

That’s when it becomes even more important to pay attention to the fishing line for any hint of a strike.

“You let the jig sink to the bottom, and pick it up about 18 inches and let it fall,” Milioto said. “A lot of times, when it gets that low, they’ll pick it up the first time they see it.”

But an unfocused angler can miss these strikes.

“Sometimes they just blast it,” Simar said. “But a lot of times, the line will just jump.

“Sometimes the line goes slack, and you have to reel up and set the hook because the fish is running to you.”

Simar and Milioto use a bright-yellow line so they don’t have to strain their eyes.

“It just makes it easier to see,” Milioto said.

When things really get tough, they’ll switch to minnows under corks.

“Sometimes they won’t hit anything else,” Milioto said.

But no matter what lure or technique is chosen, water clarity must be adequate.

“We like that clear water,” Milioto said.

That’s not hard to find in Blind River, where the water often provides more than a foot of visibility.

But heavy rains can turn the main bayous and canals soupy, especially since Ascension Parish has installed pumps that spew large quantities of water out of the Gonzales area and into the Blind River system.

That’s no problem, however, because there are areas that are always clear.

For instance, the back end of Joe Bourgeois canal generally provides plenty of clarity.

There’s also a spot off the Petit Amite that locals call the Aquarium.

“It’s called the Aquarium because it’s always clear in there,” Simar said.

The dead end in Joe Bourgeois provides the best of all worlds, with shallow and deep-water structure.

“There are stumps all along the banks,” Simar said. “You can’t see a lot of them, but they’re there.”

The anglers worked from the mouth of the dead-end, but they became more confident the farther back they went.

That’s because the water cleared up, and because the last element favored by the Milioto-Simar team was waiting.

The back end of the canal was full of pilings from old oil platforms.

“The fish will hang around those pilings,” Simar said.

The team quickly fished the trees, stumps and laydowns, and then headed for the pilings on the edge of the canal.

It didn’t take long for Milioto to get a bite, but the fish didn’t gulp the bait and the angler missed the hookset.

Meanwhile, Simar reached out and pulled his cork higher on his line, setting it to fish about 5 feet deep.

He tossed the rig past a piling, and popped the cork back to the wooden structure.

The cork bobbled, and then stood straight up.

No go on the set; the fish apparently had jerked on the tube and let go.

Simar’s and Milioto’s lures were cast to the same piling, and this time, Simar hauled in a fish.

The same piling produced a couple more crappie, along with several missed fish.

“They’ll stack up like that sometimes,” Simar said.

After working all of the pilings thoroughly, the two anglers headed for the Aquarium.

“We’ll definitely catch fish in there,” Milioto said.

The water turned a heavy brown stain when the Blazer turned into Petit Amite, but the anglers were unfazed.

“It’ll be clear in the Aquarium,” Milioto said.

Simar brought the boat off plane at the mouth of the canal, and Milioto hopped on the front deck to get a better look.

“See, the water’s mixing in there,” he said, pointing into the dead end.

Sure enough, as the anglers worked their way back into the canal, clarity became better.

Simar and Milioto worked the outside edge of the flooded trees and a distinct stump line hard, but never ventured any closer to the banks.

“You see that stump line? Anything past there is the danger zone,” Milioto said. “You want to dance with it, but you don’t want to touch it.”

That’s because the water it fairly shallow and tangled with underwater debris that is all but guaranteed to nab a jig.

The Aquarium isn’t very large, but it’s a crappie dreamland. The cover is thick, even along the stump line, so the fish often group up.

But if all of these spots fail to produce, Simar and Milioto know they can also find clean water in the Reserve Canal, which crosses under Interstate 10 just west of LaPlace.

The only problem with the Reserve Canal is that a run across the southwest corner of Lake Maurepas is necessary if the two have been fishing in Blind River.

But this is an especially productive area late in the day.

“I’ve got a couple of canals in Reserve that I can fish an hour or two before dark and catch 15 to 20 fish,” Milioto said.

So he’ll often just make after-work trips, launching right on the canal where it meets Highway 61.

“I can go in there after work and get there an hour before dark,” he said.

Sometimes the fish will be biting, but at other times, he has to fish until he can’t see his cork.

“It’ll be 15 minutes before dark, and they’ll just turn on,” he said. “You catch one fish after another.”

Regardless of which bayou or canal is fished, Simar said he pays special attention to runouts.

“I like them because they’re usually deeper, and because of all the bait they hold,” he said.

Often, it’s in these runouts that the fish will congregate to feed as water is pulled out.

“On the Petit Amite, you can fish all day and not catch a fish, and hit one of those runouts and load the boat,” Simar said.

One of the reasons most people ignore the Blind River system is boat traffic, much of which is in the form of pleasure seekers.

But Simar said that’s not a real problem during the winter, when temperatures are too chilly for most joy riders.

There are still a few fishermen, but Milioto said that’s not even much of a problem.

“People around here don’t fish much during the winter,” he said.

And that’s a mistake.

“I probably caught 300 fish in here last year,” Milioto said.

That doesn’t mean he and Simar catch fish on every outing.

“When it’s on, it’s on,” Milioto said. “But when it’s off, it’s off.”

Some water movement ups the odds of success, and Milioto said he always hopes for some out-bound current.

“They’ll bite when the water’s moving in, moving out or stagnant, but usually it’s better when it’s moving out,” Milioto said

That’s possible because the system is influenced by the tides in Lake Maurepas, which in turn are influenced by tidal movement in Lake Pontchartrain.

But sometimes other factors produce enough water movement to kick-start the fish.

“When they pump water in Gonzales, it pushes water down New River and into Blind River,” Milioto said.

That often produces current in all the connected bayous and canals, such as the Petit Amite and Bayou Conroe.