Coastal waters have looked more appropriate for gardening than fishing this year, but there are ways to put speckled trout in the boat even when the winds and rivers are up.

You could’ve read a newspaper, the moon was so bright. The nearly full orb floated in the western sky, and illuminated the marshes of extreme upper Plaquemines Parish with remarkably powerful light.

The pre-dawn darkness is always a minor hurdle for Larry Frey to clear. He’s got the well-worn route from his Delacroix camp to Black Bay saved in his GPS, and never strays more than a few feet from the path.

But a nice, bright moon makes the chore so much easier.

Still, the glowing moon wasn’t luminescent enough to show the condition of the water that May day. Had a miracle occurred that gave it a spic-and-span shine and the translucence of green-tinted gin?

Frey was sure he knew the answer to that question.

The spring of 2008 had been marred by intense and unrelenting winds. To make matters worse, the perpetual small-craft and gale warnings just happened to coincide with a season of once-a-decade river heights.

To be sure, if you were going to fish anywhere in Southeast Louisiana — with the possible exception of Terrebonne Parish — you were going to be fishing in dirty water.

But the alternative — not to fish — was out of the question for Frey, an avid, twice-a-week angler.

So even though he doubted God had sprinkled Black Bay with a proprietary water cleanser, he forged on to the “outside” during an exceptionally rare weather window with buddies Pete Rizzo and Raymond Misita along for the ride.

The roar of the outboard and the sleepy dreaminess of the pre-dawn left each man alone with his thoughts during the ride out, but each was no doubt pondering past May trips when the rhythmic clicking of noisy topwater plugs was stopped cold by ferocious explosions from furious speckled trout.

It’s a sound and an experience that is as intoxicating as any drug man or nature could create.

It’s what gets an otherwise sane individual out of a comfortable bed in an air-conditioned home at 2 a.m. to drive to the marsh and take a sometimes harrowing boat ride in the dark to be on the fish before the sun even rises.

That’s what Misita did. It’s a two-hour-plus drive for the Independence resident to even reach Delacroix, not to mention the time spent loading up his truck and, eventually, the boat, and motoring through the still-slumbering marshes to the fishing grounds.

“I won’t feel it until I get home tonight,” he said. “And then tomorrow, I won’t be worth knocking in the head.”

Like many anglers, Misita was mortgaging his tomorrow for today. But he didn’t care. He could hear clicking topwaters and trout explosions in his head, and nothing else really mattered.

At 5:40 a.m., the mission was accomplished. The boatload of anglers rounded the southeastern tip of Stone Island just as the first fingers of the eventual sunrise were painting the eastern horizon and giving a muted orange glow to the sheet-glass water.

Frey lowered the trolling motor, and squinted to see its outline beneath the murky surface. There would be no topwater bite today.

Not in these conditions.

But a group of mullet was milling about on the surface, and individual members of that crowd were going airborne every few seconds.

That was a good sign.

Frey had a topwater plug tied on, and he cast past the school — hoping against hope that a lunker trout would give him the adrenaline charge that had first hooked him a couple of decades ago.

But Rizzo threw out a blue/chrome Catch 2000, a subsurface bait that is deadly for spring trout.

Before the lure even got near the mullet, Rizzo’s rod was nearly ripped from his hands. He responded with a hard hookset, and his severely bowed rod showed the hooks had found paydirt.

Rizzo would win the battle, and Misita would net the first of the day’s 33 trout. It wasn’t a record-setting haul, but given the fresh and muddy conditions that conspired against the anglers, it was a welcome catch and a much-needed fix.

And they were able to follow it up with a dozen redfish on the way in.

This June, anglers likely won’t have to deal with as much wind as they did in February, March and April, but the fresh water will be around, a lasting legacy of the Upper Mississippi Basin’s monumental winter snowfalls and driving spring rainstorms.

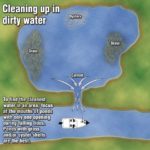

Most of the Southeast Louisiana coast will continue to be impacted. The high Mississippi will pour sweet water into Breton Sound and the bays to the sound’s west through Baptiste Collette, and since the natural currents of the Gulf pull water from the mouth of the river to the west, coastal anglers from Empire to Raccoon Point will have more than the usual amount of dirty water.

It could mean some trips will be challenging, but none will be hopeless.

“Everybody thinks trout leave muddy water. They don’t,” said Jerald Horst, a retired LSU professor and fisheries biologist. “Most really good trout fishermen have caught fish in water so muddy it amazes them.

“I’ve caught fish in a rolling, black surf that was so dirty you couldn’t see your hand one inch under the water.”

The reason anglers seem to catch more trout in clean water is because the fish have a much easier time seeing the bait, according to Horst.

“In dirty water, the fish are tougher to locate,” he said. “You pretty well have to hit them on the head. But in dirty water, they’re usually grouped up. Once you find them, you can really catch a lot.”

Capt. Shane Mayfield agrees — and he should know. This entire spring, he’s had to deal with water that’s both muddy and fresh at his favorite haunts near the mouth of the Mississippi River.

But in order for Mayfield, like any guide, to put food on his table, he has to deliver fish for his clients no matter what the conditions, and he’s been able to do that despite the barriers Mother Nature’s placed in his path.

“This year, we’ve all gotten a real good idea what to do when the water’s dirty,” he said. “Most years, you pull up to a spot, and if the water’s dirty, you say, ‘Aw, man, we’ve got to get out of here.’ This year, we haven’t been able to do that because everywhere is dirty.”

What Mayfield has done instead is learn to catch fish in off-colored water, and two things are essential — scent and speed (or lack thereof).

“Scented baits really come into play when the water’s dirty,” he said. “When the water’s clear, the fish hit a bait because of instinct; it’s just a reaction. But when the water’s dirty, they can’t necessarily react to it because they can’t see it.

“I use the Bass Assassin Blurp baits, and they really make a difference.”

Not only do the scented baits help individual fish to find the lures, they also get the rest of the school in a frenzy, Mayfield said.

“Years ago, I used to soak all my plastics in pogie oil that I got from the (menhaden) plant,” he said. “I really felt like, if I was fishing a reef or a point or something, with every cast I was putting more and more pogie oil into the water, and that would really get the fish going.”

The advent of quality scented plastics made soaking baits unnecessary, but the concept remains productive.

But the use of scent is only half of the equation. Mayfield has also found it’s vital to slow down in dirty water.

“As a guide, I’m always looking for the mother lode,” he said. “I want to pull up on a spot and wear them out.

“But in dirty water, you’ve really got to work harder. You’ve got to slow way down.”

To force himself to do that, Mayfield will ease into a historically productive area and lower the PowerPole to hold him and his clients in that area.

He’ll also be more inclined to use a cork so that his bait stays in the strike zone longer and is easier for an aggressive fish to locate.

“If you can find clean water, fish it,” Mayfield advised. “But when everything’s dirty, you want to look for what you always look for — bait and current. If you find those, the fish will be there.”

But, of course, the fresh water has been at least as much of an obstacle for coastal anglers this year as the muddy water.

Horst said that trout can tolerate lower salinity levels than most anglers think.

“Some leave, but many of them will just lay low,” he said. “They’ll kind of put their heads down; they won’t feed much, and they’ll try to ride it out.”

Mayfield has found that to be true.

“You’ll go into an area one day, and it’ll be nice and green, and you’ll catch trout,” he said. “You go back the next day, and it’ll look like pure river water, but the fish are still there.”

As the summer progresses, however, the trout will become more inclined to abandon an area that has too much influence from the river, according to Horst.

“The hotter the weather is, the less trout are able to tolerate fresh water,” he said. “It seems that the fish are able to handle low salinity in cooler weather.”

This characteristic could be because the warmer temperatures raise a trout’s metabolism, forcing it to feed more, or it could be related to the fish’s instinctive desire to participate in the spawn.

In order for a speckled trout spawn to be successful, the eggs must be deposited by the females into high-salinity waters, where they’re fertilized by the males and float into more inland waters. If the eggs are released into low-salinity waters, they sink to the bottom and perish.

Because of the abundance of fresh water this year, the early stages of the 2008 spawn may prove unsuccessful.

“It’ll depend on how long this river stays up,” Horst said. “In 1973, the river was up and up and up — everything was fresh. We also had a lot of heavy rain locally.”

All that fresh water was like a cold shower for the speckled trout. It wiped out the spawn for much of the season, and anglers paid the price two years later.

“In 1975, there were no fish,” Horst said. “That’s when the gill net wars started because (recreational anglers) assumed commercial netters had caught all the trout.”

Horst doesn’t expect a repeat of those conditions, unless the river proves more stubborn than forecasters are predicting.

But even if the spawn is curtailed, and we all pay a price in 2010, the fish are there now, and they’ll hit your slowly worked, scented baits.

Even if God doesn’t use his proprietary water cleanser.

Capt. Shane Mayfield can be reached at (504) 382-2711.