Every American chooses his treasure. For David Billeaud, all that glitters is the shiny scales of trophy speckled trout in the Vermilion Bay area.

Gold is where you find it.

For Mike Hulin, gold was to be found 41 feet underground, just off the shoulder of Louisiana State Highway 319 near beautiful downtown Cypremort Point. The stocky, straw-hat wearing man excavated the spot from October 2008 into the summer of 2010, in spite of repeated setbacks.

According to the Daily Iberian newspaper, Hulin, a native of New Iberia, was living in Surfside, Texas, when he decided to go on a 10-day fast in search of God in 1992. On the third day, he received a powerful vision.

“I saw a pirate’s grave, a captain and his sword and a beaded bag of various types of treasure,” he said.

Hulin didn’t recognize the face, according to the newspaper account, but thought to himself, “You’re nothing but a kid.”

Hulin believes that the treasure belonged to the Scottish pirate (some say privateer) Capt. William Kidd, who roamed New England and the Caribbean before being captured and then hanged in England.

The voice in the vision told him that the treasure was buried under his mother’s camp in Cypremort Point.

“It was so powerful, I was shaking,” Hulin said. “I was scared to go and look under the camp.”

But a year later, he did indeed look under the camp, and saw a 3-by-6-foot depression in the ground. When Hurricane Rita destroyed the Camp, Hulin bought the property, which his mother had been leasing.

Hulin’s dig was beset by problems. As fast as mechanical excavators and crane could dig the hole, its soggy mud walls collapsed, five times in total. Even the driving of sheet metal pilings to create a cofferdam couldn’t hold the mud back.

Hulin is convinced that two 3,000-pound trunks of treasure await him.

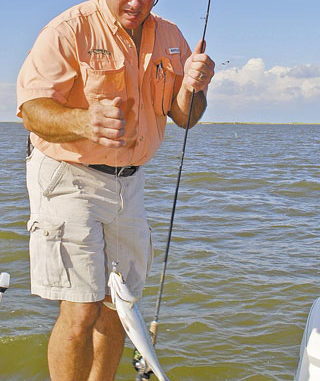

David “T-Coon” Billeaud is also convinced that Cypremort Point holds treasure for him. But his treasure has specks and fins. And, so far he has been finding it.

Like many other anglers, I follow the leader board for the CCA Louisiana STAR Tournament. Speckled trout holds the most interest for me. The final results of the 2010 summer-long fishing competition caused me to shake my head. Billeaud had won his division again!

I first met the man in 2008, when I was having to make difficult decisions about who would make the cut for the book I was writing, Trout Masters: How Louisiana’s Best Anglers Catch the Lunkers.

He already had a reputation as a trophy-trout fisherman, and had won a new boat, motor and trailer by catching the biggest speck in his division of the 2007 STAR, the largest and longest speckled trout competition in Louisiana.

That year, he not only took first place with a 7.92-pound fish, but second as well with a 7.84-pounder. He had been practicing. In 2006, the preceding year, he placed second in his division.

STAR Tournament rules state that a person must sit out a year after winning a rig. But Billeaud read the rules carefully, and noted that a person was only ineligible to claim a prize, not to compete. So he bought into the tournament again in 2008, and believe it or not, caught a 7.51-pound fish that would have claimed another boat, motor and trailer if he had been eligible.

In 2009, Billeaud again entered the competition, but didn’t get on the leader board. The bubble had burst — or so I thought. Until I read the results of the 2010 tournament. Billeaud had won his division again, and with it another rig.

I called to offer my congratulations, and Billeaud being Billeaud, he extended an invitation to go fishing.

“The fish in Vermilion Bay are just starting to turn on, and fishing should be good until late December unless it gets really cold or the river gets too high. C’mon.”

I couldn’t resist. Even though I had fished with him several times before, I had to have missed something. No one could catch that many big specks.

When I walked into his Lafayette business, T-Coon’s Restaurant, the place was packed. But I could see Billeaud’s patent leather smile and two raised arms all the way across the room. He was sitting with his brother Louis and his wife Carolyn. Their son Casey, Billeaud’s nephew and our fishing partner for the next two days, was up getting a cup of Mello Joy coffee.

Within two hours, the two Billeaud’s had the MegaBytes, David’s 21-foot aluminum Gravois, launched at Cypremort Point. Billeaud unwrapped and lit a log-sized black cigar before jumping the boat on plane. Not much had changed since we fished together last.

We headed toward the reefs outside of Marsh Island, specifically the Shell Keys, a series of reefs south-southeast of the big island. Immediately south of Marsh Island, the two Billeauds mauled some specks feeding under diving gull. Birds were diving on feeding schools of fish all around them, but Billeaud quickly lost interest in the small fish.

“I don’t feel like doing the bird thing,” he explained tersely.

A persistent wind had churned the waters near the island into a greenish murk, not good enough for the trout master. So he bypassed the Shell Keys in favor of Nickel Reef, that relic of the monster barrier of oyster reefs that once shielded Atchafalaya Bay and East Cote Blanche Bay from the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

“The water will be better there,” he said with pregnant expectation.

The 8-mile ride was bouncy, even in the deep V-hull boat.

“There she is,” he announced as the boat neared the reef, well under water on the high tide. Its location was discernable mainly by a change in the wave pattern over the reef, with an occasional wave breaking into foam.

But the water wasn’t any clearer. Still, both men wailed away with single plastic Cocahoes on ½-ounce jig heads. Billeaud threw opening night with a chartreuse tail, and Casey opted for glow with a chartreuse tail.

I watched closely to see if Billeaud’s fishing patterns had changed since I last fished with him. They hadn’t. He carefully studied the shape of the reef on his GPS screen in relation to his location, and decided how to drift across or along it.

Then he tossed out a yellow plastic drift sock to slow the boat’s drifting speed in the wind. When they picked up a couple of fish, Billeaud would quietly lower his anchor to keep the boat in position on the fish. When they played out, he picked the anchor up and continued the drift.

When the boat drifted off the reef into deeper water, Casey picked up the sock, and Billeaud cranked up the motor and repositioned the boat for another drift. His objective each time was to fish the edge of the shell reef, where the depths broke quickly from 4 to 10 feet, although on this high tide, they probed the top of the reef as well.

At the end of the day, Billeaud had done very little different than any other time I had fished with him.

The next day was again classical Billeaud-style speckled trout fishing, this time in Vermilion Bay instead of the outside reefs. The area known by local fishermen as The Cove, just west of Cypremort Point and fronting Cypremort Point State Park, received a lot of his attention. It is a classical fall and winter hotspot for catching big specks.

The two men also fished Blue Point, Mud Point and Weeks Bay, a water body almost up against the massive Weeks Island salt dome, which dominated the near horizon. Again, Billeaud drifted over extensive stretches. When they found fish, he either dropped his anchor, or if the water was shallow enough, directed Casey to spear his heavy homemade Cajun anchor, fashioned from a steel digging bar, into the bottom.

Sometimes when he reached an especially favored spot, he would drop either anchor to give it extra attention, even if neither man had caught a fish yet.

Soft plastics were their weapon of choice again. Most of the time, they bounced them off the bottom with a slow retrieve. Occasionally, one would slip on a popping cork for a change.

Nothing new. I pondered how he could catch so many tournament-winning fish seemingly doing the same thing that everyday Joe Angler did. A passing squall gave me the chance to find out.

We ran for shelter to Mark Rohrberger’s camp. Under the shelter of his friend’s covered dock, I plied him with questions and listened to his tips for success.

• Fish a lot.

“I have an unfair advantage because I am able to fish more than 95 percent of other fishermen. During the three fall months, I probably average two to three days a week. I don’t think that I am any better; I am just out there more. It’s numbers. I throw that many more times.”

• Fish on the bottom.

“I believe that big speckled trout are less active than smaller fish, and will be on the bottom.”

• Stick to your home turf and learn it.

“This is my home turf. I see 8-pound fish here. It doesn’t get the publicity of a place like Big Lake (Calcasieu Lake) because that’s where the guides are. But I fish here because it’s my home turf.”

• Learn your spots.

“I have spots that I have learned by experience over time that I have caught big fish on. I stay on those spots constantly. On the other hand, you have to be versatile too. I caught the fish that I won the STAR Tournament this year fishing from a kayak with plastic under a cork in a place that I could not get my big boat into.”

• Let the wind and the tide drift you into the spot you want to fish.

“Trolling motors still make noise too. Most fishermen come in too fast and too loud. It never fails. This is a big thing. Also, don’t make noise in the boat. Tap on the glass on an aquarium and see what happens.”

• Using soft-plastic lures on jig heads is a lot faster than fishing with live bait.

“They can keep a frenzy going. Feed fish in an aquarium — you’ll see it. I fish a fair amount of topwater lures, but have never caught anything really big on them.”

• Smash the barbs down on your jig heads so the trout come off the hook quickly.

“By keeping the fish going, it attracts other fish. In a bite, fish as fast as you can go. And the more fish that you look at, the more chance that one of them will be the big one.”

• Leave if the fish are too small.

“It sounds contradictory to fishing in a frenzy, but it’s not. It’s a judgment call, but you will know when to make it.”

• Be very persistent.

“I am on the water when the sun comes up and when it goes down. I need every hour of daylight that I can get.

“Good anglers don’t quit. The average Joe talks himself out of fishing half the time. I may reposition at a wellhead offshore seven or eight times. I’ve seen people too many times pull up to a well-head, look at their depth sounder and then leave. Nine out of 10 of my trips this year were dry trips. You spend 95 percent of the time hunting speckled trout and 5 percent catching them.”

• Watch for slicks.

“I am always looking for slicks. Because slicks drift with wind and currents, it is especially important to catch them when they first pop up and the feeding fish are right under them.”

• Don’t discount the birds.

“For the most part, trout feeding under diving birds will be smaller fish, but I have had some big trips under birds. If no other boats are around, I may drop anchor and try to keep them going in one spot by fishing fast. But lots of times I ignore birds because of the interference of other anglers.”

• Position the boat to cast with the wind rather than into the wind.

“You can cast farther and feel the bite better because you have less slack in your line. Lots of times you barely feel big trout. It is actually more of a feeling of losing contact with your bait — set the hook and it’s a big trout.”

• Moderate tide ranges are best.

“A 2-foot range between sun-up and noon is just too much. I really like to hit my favorite spots on switching tides.”

• Stay in Vermilion Bay whenever possible.

“That is where I find my real big trout. But when the Atchafalaya River is too high, over 10 or 11 feet, or when it is so windy that the bay is muddy, I fish the reefs outside of Marsh Island. Wind direction is important too. A west wind will really muddy the bay, but is good when the river is high and putting muddy water on the reefs offshore.”

Billeaud recommends that fishermen new to an area learn it by fishing it hard, watching what other anglers do and talking to them.

“Lots of people come up to me and talk fishing at my restaurant,” he said. “It happens all the time. I’ll probably take them fishing. I’ve taken three or four this year that I have never met before.”

If you drop by the restaurant, go on a Monday. That’s when they serve the smothered rabbit.