Restoration plan relies on state, federal revenues for $50 billion budget

Editor’s note: This is the third installment of an ongoing series about the state’s Master Plan for coastal restoration, hurricane protection and flood control.

While all of the manpower and dirt-turning is located on Louisiana’s coastline and in the Gulf of Mexico, some might argue that the real grunt work of coastal restoration takes place some 1,200 miles away in Washington, D.C. — where the state expects to get the lion’s share of the $50 billion needed for its 50-year Master Plan that has been approved by the Louisiana Legislature and Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

Last month found U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu of New Orleans working those very angles. During a hearing before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, she pointed out that the Gulf Coast contributes $3 trillion a year to the national economy through its ports and energy activities.

“All the while, we are losing our coast at the rate of 25 to 35 square miles a year, or about a football field each hour,” Landrieu said, adding that continual erosion is a “result of years of federal underfunding and neglect that continues to this day.”

Landrieu is pushing something called the Fixing America’s Inequities with Revenues Act, which is known by as the FAIR Act. She introduced the legislation to ensure all energy-producing states — not just Louisiana — receive a fair share of the revenues they help generate. It’s also money that Landrieu has couched as an important investment in Louisiana’s Master Plan for the coast, should the act pass and be signed into law.

While onshore-producing states keep 50 percent of royalties, rents and bonuses, offshore-producing states like Louisiana receive virtually nothing. The FAIR Act aims to address this inequity by authorizing 37.5 percent of revenues for all offshore energy-producing states, regardless of the type of energy produced.

The FAIR Act would also gradually lift the current congressionally mandated $500 million annual cap on revenues kept by Gulf Coast energy-producing states.

Reggie Dupre, executive director of the Terrebonne Levee and Conservation District, also testified before the committee.

“Passing legislation that rectifies the inequitable treatment between on(shore) and offshore states with respect to revenues generated by federal oil and gas activities is not only fair, but will allow the state of Louisiana the ability to restore and protect our vanishing coast,” Dupre said.

Dupre wasn’t alone in that support. Amont those speaking on behalf of the legislation were representatives from the National Ocean Industries Association, Women of the Storm, Restore or Retreat and America’s WETLAND Foundation.

While that might sound like overwhelming support, the FAIR Act has actually run up against significant opposition — chiefly from President Barack Obama, whose administration has stated a preference for programs related to alternative energy, and from environmental groups like the Sierra Club.

It’s a near-perfect example of the challenges Louisiana officials face in gathering the funds necessary to underwrite the Master Plan. Nothing is guaranteed.

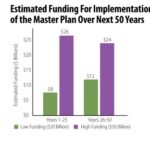

That’s why the $50 billion figure that’s often cited is considered the upper end and most-positive of estimates. Officials actually believe the state will receive somewhere between $400 million and $1 billion annually between now and 2061. (The amount of $1 billion annually will be needed to create a $50 billion budget.)

Moreover, there are qualifications, such as the fact that funding might be spaced out over several years and not arrive in perfectly allocated chunks.

There are, however, some certainties, like the Coastal Wetlands Planning Protection and Restoration Act that will provide about $80 million per year and the Louisiana Coastal Area program that could be good for about $150 million per year.

Other federal sources that could be relied upon include the Coastal Impact Assistance Program, Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act and the Energy and Water Act.

There are also opportunities through carbon and nutrient credits, which can be traded or sold to other entities when Louisiana has projects that affect the presence of both in the area.

The state is a key player, as well. Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Fund feeds into the larger pot, since it holds constitutionally dedicated revenues from sources such as state mineral leases. Money is also sometimes made available through the state’s annual spending plan and construction budget.

But, according to the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s Garrett Graves, the Master Plan has received its largest “down payment” courtesy of two federal sources connected to the 2010 BP oil spill: the Deepwater Horizon Natural Resources Damage Assessment process and Clean Water Act fines.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation is overseeing some of the appropriations — about $2.5 billion that has been coughed up by BP and its partner Transocean, of which roughly half is destined to help Louisiana with barrier island and river diversion work.

But that’s only one piece of a larger pie.

This summer, CPRA made a formal request for $68 million from the Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The request included $6 million for upgrades to East Timbalier Island and $3 million for beach enhancements on Caminada Pass. The rest was for diversion projects, such as $4.9 million to accelerate the flow of the Atchafalaya River into Terrebonne.

There were also requests for sediment diversions, including $40 million for mid-Barataria Bay to Myrtle Grove, $4.8 million for Lower Barataria, $4.5 million for Lower Breton and $4.3 million for mid-Breton Sound.

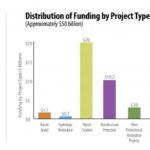

Just as important as gathering the money needed for the Master Plan’s $50 billion budget is how it will be spent. Based on the plan’s developing budget, spending by project type should end up looking like the following:

• Marsh Creation — $20 billion

• Structural Protection — $10.9 billion

• Nonstructural Protection — $10.2 billion

• Sediment Diversion — $3.8 billion

• Other Protection and Restoration — $3 billion

• Barrier Islands — $1.7 billion

• Hydrologic Restoration — $700 million

Yet, as with any plan, things can change. Local levee districts waiting for work to be performed through the Master Plan might very well come into their own loot.

For example, the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East turned heads in July when it filed a lawsuit against 97 companies in Civil District Court in New Orleans seeking no specific dollar amount but demanding that the oil companies immediately restore damages to wetlands caused by decades of energy exploration, including dredge work and the crisscrossing of canals through coastal marshes. A vigorous and protracted legal fight is expected.

That just goes to show there are many unknowns in the funding game for Louisiana’s Master Plan, which goes double for Landrieu’s proposed FAIR Act.

Anne Milling, founder of the advocacy group Women of the Storm that was created in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, told lawmakers during testimony on the bill that the federal government can either put up the cash now or wait until after hurricanes blow through and erosion overplays all else.

She said the latter course would probably result in even more federal spending than what’s being requested today.

“It is an injustice that our communities have endured for far too long, and it is time for it to end,” Milling said.