Despite support from Bayou State hunters that has been unwavering over the years, a close analysis shows that Louisiana may be an afterthought for the nation’s largest waterfowl conservation organization.

O.K., let’s start with the obvious: For the last two seasons, duck hunting in Louisiana has been, at best, disappointing. The anticipation of hunters has been buoyed the last two summers by breeding-ground numbers that indicated declining but still very strong populations of ducks spread throughout Canada and the northern-tier states.

When entered into the federal formula, these numbers called for liberal season lengths and bag limits, further whetting the appetites of Louisiana’s duck hunters, who, by nature, are a fervent and fanatical bunch.

But, of course, as all duck hunters know by now, summer’s promise has led to winter’s heartbreak for at least the last two seasons.

Duck-hunting success in Louisiana has been spottier than a 12-inch speckled trout.

Since the 2002-03 season ended, hunters have been demanding answers, and they’ve formulated a theory amongst themselves that on the surface seems preposterous but may hold in its core a kernel of truth.

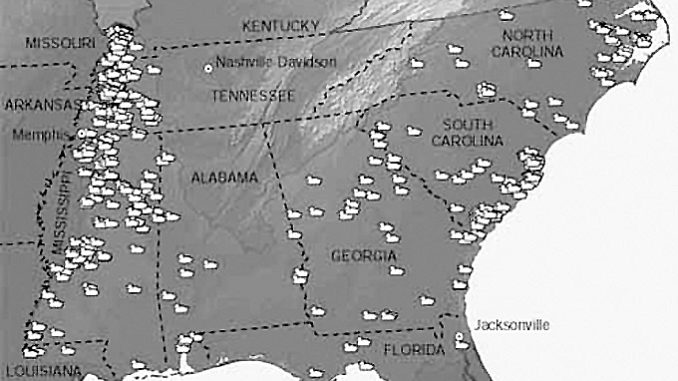

Specifically, Louisiana hunters are charging that many of the programs sponsored and paid for by Ducks Unlimited are enriching wintering grounds in more northern states, like Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri, giving ducks a comfortable place to spend the coldest months of the year.

Some of these hunters are even claiming that DU is spreading feed across the Midwest to keep ducks from leaving grounds that are important to major sponsors.

DU is funding all these projects, hunters are charging, while neglecting the rapidly eroding wetlands in southern Louisiana.

Representatives from DU have denied the charges, but Louisiana hunters have been relentless.

Consider these posts from louisianasportsman.com:

“We the duck hunters pay for DU to survive. I think that DU did a lot of good things early on when they focused on the breeding grounds, but the minute they stepped across that line is when all hell broke lose.

“I am a 14-year bronze sponsor, and last year was my last. In fact, I have already called and cancelled my membership.

“I agree that weather does dictate the speed of migration, but I can remember many years much milder than this one when I was killing mallards in a short-sleeve shirt, not blue wing teal in full plumage in January.”

— Spoiler from Lafayette

(Jan. 30)

“I also feel violated and smoked about DU. As a bronze sponsor for 9 years, I quit.

“This year, we had 27 hunts with 17 ducks on a private lease that usually gives more than 450. I took more when the limit was three.

“Look at DU’s Web site on rice. That should wake us all up on where my money went to. I always thought it was going to protect nesting areas. I guess that the lawyers are starting to run and ruin DU as they do to our insurance rates.”

— Hurt Too from Labadieville (Jan. 30)

“On the DU debate, I really don’t think DU is purposefully short-stopping ducks from getting to Louisiana. DU knows that this would be counter-productive for them financially.

“However, given the projects that they have undertaken and the weather we’ve had, that is precisely what is happening. The biggest problem I see is that the young ducks will never know Louisiana exists as long as there is ample food and decent conditions up north.

“While I don’t think DU needs to be vilified by Louisiana hunters, they do need to hear our complaints and take action to aide some of their biggest supporters.”

— Ted from Lafayette

(Jan. 29)

It’s easy, and perhaps tempting, to shrug off such posts and opinions as alarmist propaganda being spouted by a small but vocal group that simply can’t accept the whims of nature.

But the facts show that, at least on some level, the hunters may be right.

At this point, Louisiana has within its borders 40 percent of the nation’s coastal wetlands, and that’s precisely why our duck hunting is typically so good. But that 40 percent, of course, is a number that’s shrinking by the day.

Louisiana residents have known for years that our coast is eroding under our very feet. Those who hunt ducks or cast for fish in the marshes below Interstate-10 see the evidence every time they head afield. They don’t need to read statistics and look at graphs that show Louisiana is losing 70 acres of coastal marsh every day.

Standing alone, the numbers are tough to visualize. But a hunter can see with his own eyes that five years ago, he had 100 yards of marsh between his favorite duck pond and a nearby lake, and today, his formerly favorite duck pond is now part of the lake.

But at least until very recently, this ghastly coastal-erosion issue has gotten little of the attention it deserves from national figures, including, arguably, the movers and shakers at DU.

DU clearly recognizes the traditional importance of Louisiana’s marshes to ducks. Their own Web site states that “the Louisiana coastal marshes annually provide winter habitat for 60 percent of the entire Mississippi Flyway waterfowl population.”

That’s a mind-boggling statistic, and it’s one, obviously that DU accepts.

“In my opinion, the marshes of coastal Louisiana are very important for duck populations continentally,” said Hugh Bateman, DU’s manager of conservation programs for Louisiana. “On a scale of one to 10, the value of the Louisiana marshes (for duck populations) is a 10.”

But DU’s attention to the marshes that are so crucial to “60 percent of the entire Mississippi Flyway waterfowl population” arguably hasn’t been commensurate with the importance of the marshes.

According to the most-recent numbers available, DU has spent nearly $122 million to date on duck-habitat projects in the Mississippi Flyway. That’s a whole lot of money, and it could go a long way toward preserving the wintering habitat that is so important to so many Mississippi Flyway ducks.

But only $16.5 million of that money — 13.5 percent — has been spent here in Louisiana, according to statistics provided by DU.

One might argue that DU is a member-funded organization and that, even though Louisiana is very important to wintering waterfowl, DU has to spend its money in its members’ “backyards” in order to keep the dollars flowing.

But actually, a quick look at DU’s own numbers debunks that argument.

In 2001-02, Louisiana ranked first among the 50 states in total miscellaneous event income for DU, third in total DU sponsors, fifth in total grassroots income for DU and fifth in total DU members.

Louisiana is clearly among the five most-important states financially for DU. But some hunters are wondering if that support has been taken for granted.

That’s not the case, according to Don Young, executive vice-president for DU.

“From a purely fund-raising perspective, Louisiana represents one of our most-important states, so why would we want to alienate our membership base by hurting the duck hunting in that state?” he asked.

Young said charges that DU is feeding ducks to hold them in Midwestern states “lack common sense.”

“We are not feeding ducks nor keeping water open in areas that would normally ice up,” he said.

Young explained that he is an avid duck hunter, and any “short-stopping” done in the Midwest would hurt his hunting grounds in Arkansas as much as it would those in Louisiana.

“Only a very nominal amount of our expenditures are on moist-soil habitats in the Midwest, and what improvements we do make there are meant to benefit northward-migrating waterfowl in the springtime,” he said.

The highest proportion of DU’s expenditures are on the breeding grounds, Young said. That’s because DU scientists have determined breeding grounds are far more crucial to the overall health of duck populations than wintering grounds.

“If the breeding grounds are healthy and ducks have breeding success, that benefits hunters all up and down the flyway,” he said.

Still, he said DU is “very concerned” about Louisiana’s coastal wetlands loss.

That sentiment is showing up in DU’s approach to the coastal marshes of Louisiana, Bateman said.

“The value of the marshes is the top issue for (DU) here in Louisiana,” he said. “That’s why we’ve now begun spending so much money on coastal issues.”

The numbers comparing how much DU has spent in Louisiana with the rest of the flyway are misleading, Bateman said, because from DU’s founding in the 1930s through the mid 1980s, the organization did all of its conservation work in Canada. Its first non-Canadian project was at Louisiana’s Marsh Island Refuge in 1985.

Further, no DU staff even existed in Louisiana until 1992, and the first staffer charged with exclusively coastal issues wasn’t brought on board until 1999.

DU has a 5-year continental plan, and projects along coastal Louisiana play a significant role in the current plan, Bateman said. DU’s approach now in Louisiana is to supplement projects that are being worked on by government agencies.

“They’re doing projects that cost many millions of dollars. What we want to do is come under those projects and make them as beneficial to waterfowl as possible,” he said.

Young agreed that DU has taken a more proactive stance on the Louisiana marsh as of late.

“I was there when Gov. Foster made the announcement about the America’s Wetlands campaign,” he said. “We are the most prominent conservation group that has stepped up to the table to bring this issue to light.”

Young noted that, to date, DU programs have saved or enhanced 200,000 acres of waterfowl habitat in Louisiana.

But still, Louisiana loses 35 square miles of valuable marshland every year. Certainly DU isn’t responsible for the wetlands loss, nor could the organization stop it entirely even if it poured all of its resources into the Bayou State, but many hunters wondered during the season if they were beginning to see the effects from years of unabated coastal erosion.

Young counters that even with the rapid loss of our waterfowl habitat, duck hunting in Louisiana is far better than that of other states.

“Cameron Parish kills more ducks each year than the entire Atlantic Flyway,” he said. “The state of Louisiana kills more ducks (each year) than Canada and Mexico combined.

“During the ‘glory days’ of the ’70s, Louisiana killed 1.5 (million) to 1.8 million ducks each year with a 10-bird (per hunter) limit. In the 2000-01 season, Louisiana killed 2.1 million ducks, and that’s with a six-duck limit. So, just two years ago, Louisiana had a near-record harvest.”

Young admits that Louisiana’s hunting hasn’t rivaled those numbers the last two seasons, but that’s because conditions haven’t been favorable, he said.

“It’s clearly a weather-dominated issue,” he said. “I hunted the Mississippi Delta toward the end of the season, and it looked like an ocean down there. There were plenty of ducks, but they were just so scattered.”

Young said Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba had record cold in October 2002, which forced birds into Midwestern and even southern states.

But that cold weather didn’t last through the season.

“Saskatchewan and Alberta had 65-degree highs in January,” he said. “Right now, there are hundreds of thousands of mallards in southern Canada.”