Ever hunted a dust trail? I have.

It’s my fault. I should have moved quicker.

But I lingered a little too long picking up snacks and Dr. Pepper in the little store in the big curve on Hwy. 165 at Riverton (that’s not there today). I almost never caught up with Byron Rogers in his old Chevy pickup.

I was in a group heading on a season-opening squirrel hunt deep in the Caldwell Parish woods, and while I knew where to turn off the main highway, I wasn’t sure which of the dozen or so gravel and dirt roads to turn on after that. I had never been where we were going. No cell phones. No GPS. No 911 address signs.

Good guesses

Fortunately, we made a couple of good guesses and there ahead, was a little wisp of dust in the air from the pickup truck caravan in front of me. I made it to “camp,” a clearing on the edge of a big timber company hardwood bottom. Back in the day, lands like these were open to the public. That was before irresponsible hunters abused the privilege and those companies found big bags of lease dollars in their woods.

Successfully hunting and finding the dust trail led to a great weekend. It was much better than the alternative, an unscheduled tryout for “Alone.”

We shot squirrels. We ate squirrel mulligan. We told lies. And, as always, we watched our backs. Somehow as I tracked the dust trail, I knew in the back of my mind that Big B would slow down enough for me to catch him, or at least he would send somebody back looking for us in a few hours.

But Byron was never one for shying away from putting a Vienna sausage in your squirrel mulligan or hiding your box of No. 8 shot right before daylight the morning of the hunt.

Such was the way of the outdoor activities that I pursued with my old Forrest Street neighbor. Big B passed away about five years ago and I hope those Angels up there have adjusted to him by now.

The little Blue House

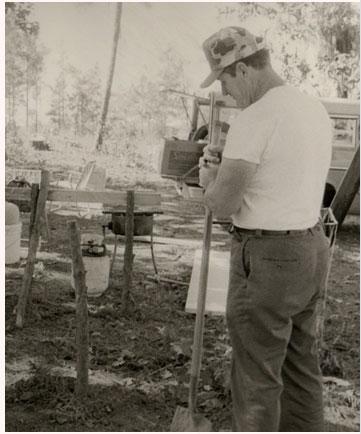

I recall one visit to the little “Blue House,” a camp that Byron engineered, helped build and supervised untiringly.

I went on a squirrel hunt another season at the little Blue House one weekend on the banks of the Tensas River. Byron was just a half dozen weeks past having kidney surgery. It was his first outing. He was supposed to be really taking it easy. No bouncing around or anything strenuous. Part of squirrel hunting at the Blue House was climbing down an old iron ladder which looked like it came from the salvage yard at the local paper mill where we both worked. Big B would say it’s where he worked and where I held a job. We went down the ladder, into an aluminum boat, across the river and up a steep clay bank to some fine, hard-to-reach squirrel woods.

But when Byron got to the bottom rung on the rusty old ladder, it broke. He went down not one foot, but about three, landing pretty hard on his feet. I looked at him. He looked at me. After a second that lasted two minutes, he broke the silence.

“I wasn’t supposed to do that,” he said. He assured us he was okay. More squirrels were killed. More lies told. And I’m sure somebody had a Vienna sausage in their squirrel mulligan.

Coming home from work late at night, I often found the light on down the street, where many late night talks took place about his one-time dreams to be a major league umpire or mine about being a professional bass fisherman. They stayed dreams because we had families to take care of. The discussions were entwined with more serious discussions about life.

Good life advice

When I went to work at the mill, he was a Union Chairman and I was a salaried “white hat,” the term the “working people” had for supervisors. It could be a fairly high pressure job in a tough work environment. Two weeks hadn’t passed when he came through my door and closed it.

He told me, “You didn’t ask for this, but I’m going to tell you anyway. Don’t get too caught up in this job or the company. Don’t let it change you. Don’t try to be somebody you’re not. Just be Kinny and you’ll be just fine,” he said.

When the love of my life came to my home town for the first time, Byron and his wife, Zanona, held a neighborhood Fourth of July barbecue. I remember B took an opportune time and asked, “I know she looks good, but can she see good?”

One time, he took me way back in the Ouachita River swamp to a small but-ton willow-lined lake that had almost as many big bass in it as water moccasins. We had to maximize the power of a big-tired four wheel drive Jeep just to get there. There was only one condition — I couldn’t write about it, at least not tell anybody exactly where we were. Well, I wrote about it. I didn’t tell exactly where we went, but I must have done a pretty good job describing it because he told me everybody knew.

“I knew you were going to do that,” he said, looking like he would have liked to hit me with one of those big pipe wrenches he used at work.

Byron was one of the good ones. A real person. He tried to act tough, and could be if necessary. But he would help anybody who was willing to try and help themselves and some who weren’t. That’s why he was loved by so many people. He didn’t give out advice he didn’t follow himself. He didn’t let life change him. He didn’t try to be somebody he was not. He was just Byron and that was just fine.