From its unrefined beginnings, the Red River has emerged as one of the best recreational waterways in the country.

When the Freeman-Custis Expedition explored the Red River in 1806, it became apparent that the river’s odd features hampered its commercial potential. A massive log jam known as the Great River Raft blocked the river above Natchitoches, and a long stretch of rapids at Alexandria interrupted boat traffic there during times of low water. To make matters worse, the river’s high salt content made it useless for irrigation.

Twenty-five years passed before the federal government attempted to open the river to steamboat traffic. No one envisioned it would take nearly 50 years before success was finally achieved.

In February 1833, the War Department ordered Capt. Henry Miller Shreve to begin work clearing the raft. Shreve (1785-1854) was the Superintendent of the Army Corps of Engineers’ Western Waters Department and one of America’s most famous steamboat designers and pilots.

On April 1, 1833, Shreve arrived at the foot of the raft with eight steamboats and snag boats. His work force grew to 300, and he later reported, “As relates to the expense of removing the raft, it will be repaid at least threefold by the lands that must be redeemed on the immediate line of the raft. All that land is of a first rate quality for the growth of cotton, and there is now growing the best tobacco made in the U.S. on several improvements now in cultivation on the river, about midway of the raft.”

One of the boats Shreve relied on was the Heliopolis, which he had designed a few years earlier (amazingly Shreve registered 22 patents as a result of his work on the Great River Raft). On its bow resembling a giant jaw was a steam-powered windlass that could pluck logs from the water and run them through a saw mill set up on the deck.

The recovered logs and boards produced by the saw mill were used to dam up bayous such as Saline to keep them from entering the river and raising the water level. A congressional report later declared, “One snag raised by the Heliopolis … contained 1,600 cubic feet of timber, and could not have weighed less than sixty tons.”

It took Shreve six years to complete the work, but he finally cleared approximately 150 miles of river. Soon, dozens of steamboats were plying the Red, and in 1850 one-eighth of the nation’s entire cotton crop was transported on the river.

Unfortunately, the clearing of the raft had unforeseen consequences. The raft acted as a dam and caused water to back up in tributaries to form lakes such as Bistineau, Black, Saline, Iatt and Nantachie. When the raft was cleared, the water drained out of the lakes, and they dried up except during the wet season.

Even Natchitoches was adversely affected by the clearing of the raft. As more water began to flow down the Riviére de Petit Bon Dieu, a small branch of the Red River in the St. Maurice area, Cane River, on which Natchitoches was established, virtually dried up in the summer time. Natchitoches ceased being a major river port.

One town’s loss, however, was another one’s fortune. After clearing the Great River Raft, Shreve and his business partners established a port of their own on the upper river. In 1836, the port was incorporated as Shreveport.

The Red River remained dangerous even after the raft was removed. In 1838, the federal government contracted the Heroine to take supplies to Fort Towson in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). It was one of the first steamboats to use the newly cleared channel, but the Heroine struck a log and sank just a couple of miles shy of its destination.

Despite the danger, virtually anyone could guide steamboats on the Red River by obtaining a pilot’s license for just $5. One such person was Bill Sandusky.

Once while piloting a new steamboat upstream, Sandusky entered a particularly dangerous stretch of water. When the ship’s captain openly expressed doubts about Sandusky’s familiarity with that part of the river, Sandusky declared, “Why, cap’n, I know every rock and snag in the whole creek.”

At that moment, the steamboat ran into a snag that tore through the bottom of the boat and came out on the hurricane deck. Unruffled, Sandusky simply exclaimed, “There, cap’n. I told you I knew where every snag there was, and there’s one of ‘em!”

One of the most frustrating things about the Red River was that the log jam quickly reformed unless snag boats worked constantly to keep the debris plucked out. Almost immediately after Shreve cleared the original raft, a new one developed above Shreveport that stretched 20 miles by 1841.

Despite several more attempts to clear the raft in the 1840s and 1850s, it continued to grow, and in 1860 engineers estimated it would take five years to clear it again.

Unfortunately, the Civil War put a hold on further work. During the war, steamboats and ironclad gunboats moved up and down the river below the raft between the Mississippi River and Shreveport, and many of them were sunk during the bloody Red River Campaign of 1864.

In that campaign, a large Yankee army under Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and dozens of navy vessels under Adm. David Porter launched a massive invasion up the Red River to capture Shreveport. Confederate forces, however, defeated Banks at the Battle of Mansfield, and forced him and Porter to retreat.

When Porter arrived at Alexandria, he was horrified to find the river had fallen so low that he could not get his vessels over the rapids. What he did not know was that Rebel engineers had ingeniously opened up Tone’s Bayou and drained out as much Red River water as possible.

Porter’s largest ironclads drew 7 feet of water, but the river at the rapids had fallen to 3 1/2 feet. With the Confederates closing in behind him, Porter was trapped and made plans to destroy his ships to keep them out of enemy hands.

Fortunately for Porter, Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, an engineer with logging experience, came up with a plan to dam the river and raise the water level at the rapids. At first, Porter was not impressed with the idea. He had struggled against the Red’s low water for weeks, and one man claimed he jokingly declared, “[I]f damning would get the fleet off, he would have been afloat long before.”

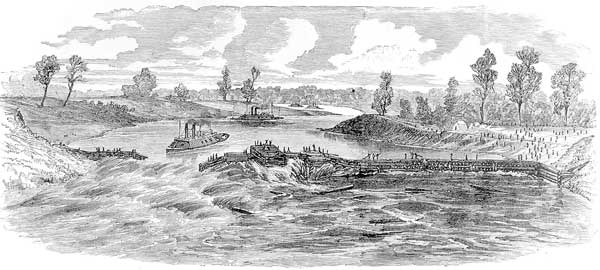

Porter had few options, however, and he and Banks agreed to give Bailey a chance. Soon, thousands of Union soldiers were working furiously on the project. On the Pineville side of the river, the dam was constructed from felled trees, while on the Alexandria side, cribs filled with rock and material taken from torn-down buildings were sunk in the river.

When these two “wing dams” narrowed the river, barges were loaded with rocks and sunk in the remaining gap. Even stones from Pineville’s Louisiana Seminary of Learning (the forerunner of LSU) were used. The plan was to break the dam when the river had been raised sufficiently and let the ships ride the rushing water over the rapids.

Bailey’s Dam proved a success, and the U.S. Navy escaped. Despite his initial resistance, Porter afterward proclaimed it was “the greatest engineering feat ever performed.” In recognition of his service, Bailey was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Today, remnants of Bailey’s Dam are still at Alexandria. Before the J. Bennett Johnston Waterway was completed, the old dams could be seen jutting out from the bank just below the U.S. Highway 167 bridge.

When the Civil War ended, the federal government once again was able to send snag boats up the Red River to clear out the reformed log jam. By the time work began in 1872, Alfred Nobel (of Nobel Peace Prize fame) had invented dynamite, and workers used it to blast the raft all the way to Fulton, Ark. Still, it required constant work over the next 10 years to keep the river open.

Not everyone was thrilled with this last clearing project. In 1873, a yellow fever epidemic broke out in Shreveport that killed 759 people — 10 percent of the city’s population. Among the dead was Lt. E. August Woodruff, the Corps of Engineers officer supervising the work on the log jam.

At that time, it was not understood that mosquitoes carried the deadly yellow fever, and many people blamed the epidemic on noxious gases that were stirred up from the river’s bottom during the raft-clearing work.

Even though the Great River Raft was finally cleared, the Red River remained dangerous and difficult to navigate. During times of low water, newspapers regularly carried stories of steamboats running aground on sandbars. On Oct. 11, 1879, the Lafayette Advertiser reported the water was so low that boats could not reach the Atchafalaya by Old River or Red River.

Gary Joiner, a history professor at LSU-Shreveport, has located 14 sunken steamboats just in the Shreveport area, and estimates there might be as many as 300 wrecks on the entire river.

The removal of the Great River Raft finally allowed officials to turn their attention to clearing a channel through the rapids at Alexandria. When he examined them in 1806, explorer Thomas Freeman did not believe it would be a very difficult project. He was badly mistaken.

A narrow channel had previously been cut through the lower rapids in 1854. A short article in the New York Times on Feb. 21 declared, “[W]e learn that the submarine operators, Messrs. Maillefert and Raasloff, have made great progress of late in widening and deepening the channel of the Red River, through the Lower Rapids at Alexandria. They have now a channel through the whole ledge forming the lower falls, over 350 feet in length, 40 feet in width, and of an average depth of four feet.”

Unfortunately, the newspaper did not give any details of the work, and it is not known whether the men actually used submarines on the river.

The Corps of Engineers eventually took over the project, but it discovered a layer of rock lay underneath the clay shelf. This greatly slowed the work, and the Corps did not complete the channel until 1897 — fourteen years after it began.

During the 20th century, government officials began addressing problems created by the clearing of the Great River Raft. Because all of the Red River began running down the Riviére de Petit Bon Dieu, Cane River at Natchitoches virtually dried up. In 1915, two earthen “bridges” were built across Cane River, but they actually served as dams to create Cane River Lake.

Steps were also taken to recreate the Raft Lakes that drained out when the log jam was removed. In the 1920s and 1930s, dams were constructed to hold water permanently in Cross Lake, Lake Bistineau, Black Lake, Saline Lake and others.

Despite the improvements made on the Red River, it continued to taunt farmers because they could not use its salty water for irrigation. Sportsman also found little use for the river because the heavy sediment made it difficult for any fish other than catfish to survive in the muddy water.

Businessmen were more concerned about using the river for commercial traffic. Unfortunately, despite the clearing of the raft and the cutting of a channel through the rapids, the Red remained so shallow during the summer that it was impossible for barges to go beyond Alexandria.

By the late 20th century, the Red was the largest undammed river in the United States. Shreveport and Bossier City sat on the bank of the second-largest river in Louisiana, but were unable to tap it for commercial transportation.

To correct this, the Louisiana legislature created the Red River Waterway Commission in the mid-1960s to work with Congress to make the river navigable all the way to Shreveport. Fortunately, at that time in history Louisiana had some of the nation’s most powerful politicians, including Allen J. Ellender, Russell B. Long, Joe D. Waggoner and J. Bennett Johnston.

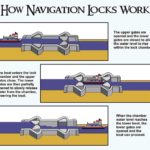

Sen. Johnston, in particular, pushed a plan to build five locks and dams on the river, and in the 1980s he and others convinced Congress to appropriate approximately $2 billion for the project. Completed in 1994, the newly dammed river was named the J. Bennett Johnston Waterway.

The locks and dams created five pools and a 9-foot-deep and 200-foot-wide channel that stretches from the confluence of the Old and Red rivers to Shreveport-Bossier City. The locks are 84 feet wide, 705 feet long and provide 141 feet of lift.

The dams also help control flooding, and they allow both the salt and sediment to settle to the river bottom by slowing down the current. Water quality has greatly improved, and many fish species now thrive in the pools. Today, the Red River is one of the most popular fishing spots in the South, and many farmers are using its water for irrigation.

The J. Bennett Johnston Waterway has far surpassed anyone’s dream as a fishery. There’s a reason why that’s the case, according to Mike Wood, a fisheries biologist with the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

“Without the flow that it takes to keep solids suspended, it becomes beautiful, fertile water, and a bass fishery has developed that’s just out of sight,” he said. “We sample the Red River, and we’re very impressed with the trends of largemouth bass growth. It’s just a really good fishery.

“Reproduction is good. In addition to that, Florida bass were stocked into the pools in an effort to increase the potential for larger bass. We’re trying to take advantage of this very good habitat.”

Over the last decade, the Red River has become a bass fishing mecca, and a huge 13-pound, 8-ounce behemoth has been taken from Pool 5.

Earlier this year, the 39th Bassmaster Classic was held on the Red at Shreveport/Bossier City. Skeet Reese won the three-day event with 54 pounds, 13 ounces. That was just two pounds shy of the record set in 2006 on Florida’s Lake Toho.

Today, the federal government is further enhancing Northwest Louisiana’s recreational potential by creating a federal wildlife preserve in the area. In 2001, the Red River National Wildlife Refuge Act was signed to create a federal wildlife refuge containing approximately 50,000 acres along the river between Colfax and the Arkansas state line.

When completed, Red River NWR will have four units: Lower Cane River (Natchitoches Parish), Spanish Lake Lowlands (Natchitoches Parish), Bayou Pierre Floodplain (DeSoto and Red River parishes) and Wardview (Caddo and Bossier parishes).

This massive project will provide Louisiana sportsmen with countless outdoor recreational opportunities, and will culminate more than 150 years of trying to tame the mighty Red River.