With speckled trout and redfish action that is unrivaled in the country, with clouds of ducks filling the skies most winters, with near-shore waters that teem with cobia, dolphin and snapper, Louisiana is rightly dubbed the Sportsman’s Paradise.

But the marsh that serves as the very foundation for those staggering fish and game stocks is disappearing, and in many places it’s totally gone. Unless serious, costly and painful steps are taken within the next five years, the Sportsman’s Paradise will become Paradise Lost.

Like morning dew in the glare of a rising sun, the Louisiana coast is vanishing before our very eyes.

It’s a loss that threatens our traditions, our livelihoods and, equally as important for many, our fisheries. Once gone, most of the tracts of marsh are irreplaceable, and so too are the fisheries they supported.

Home to 40 percent of the nation’s coastal wetlands, Louisiana experiences an astounding 80 percent of the entire nation’s coastal wetland loss.

The cost to the nation to fix the long-ignored problem — $14 billion — is only a fraction of the inevitable cost if the inaction continues — $100 billion in infrastructure alone.

The loss of the Bayou State’s jagged coast line will be harmful for America, and for Louisiana it will be devastating.

The Louisiana coast is, by far, the most productive fishing ground in North America. A full 95 percent of all Gulf marine life spends at least a portion of its existence in Louisiana, and native and visiting anglers who have sampled the marsh fishing along the Bayou State coast don’t find that figure hard to believe.

Texas and Florida, both states with speckled trout resources that are far better known nationwide, have creel limits of 10 and minimum length limits of 15 and 14 inches, respectively, on the species. Anglers in those states admit, however, that trips resulting in limits are rare events.

But in Louisiana, anglers expect to go out and catch their liberal limits of 25 fish exceeding a mere 12 inches in length on every trip. The Bayou State’s fishery is truly second to none.

The reason that fishery is so special is because Louisiana sits at the mouth of the world’s third-largest river basin. For thousands of years, the Mississippi River collected sediment and other deposits from the Plains and Midwestern states and hand-delivered them to the shallow edges of the continental shelf along the Louisiana coast.

Over time, this sediment would build up and eventually block the path of the river, so she’d jump her banks and, by the powers of gravity, find a less-obstructed path to the Gulf. Then the land-building process would begin anew along another section of the Bayou State.

The parishes of Plaquemines, St. Bernard, Orleans, Jefferson, St. Charles, St. John, Lafourche, Terrebonne and St. James and portions of Assumption, Ascension, Livingston, Tangipahoa and St. Tammany owe their very existence to the alluvial soils deposited by the Mississippi River.

The shallow, broken marshes the river left behind were the perfect breeding and nursery grounds for a cornucopia of marine life, including speckled trout and redfish. Indeed, if a group of biologists had gotten together to design a place where specks and reds would thrive, it wouldn’t have looked much different than coastal Louisiana prior to 1927.

The outer coast was lined with barrier islands and their bait-filled beaches and adjacent deep-water passes, where specks and reds could feast and spawn during the summer months.

Inside of those islands were endless stretches of cord-grass flats, broken only by tidal ponds and lakes filled with shrimp, minnows and crabs. In these fertile marshes, baby speckled trout and redfish, the fruit of the spawn swept in with the tides, could eat at will and grow rapidly through the fall, winter and spring, fully protected from the larger predators of the exterior bays.

Erosion and saltwater intrusion occurred in that near-perfect ecosystem, but only in isolated areas that were being ignored for that season while the Mississippi built land elsewhere. Before long, the river or one of her fingers would return with the land-building load.

The death throes of this idyllic world began in 1927, when the great river carried run-off from torrential rains up north into the Bayou State, flooding Louisiana towns from Bordelonville to Braithwaite. Houses were swept away like sand castles in a rising tide, and businesses and family farms were destroyed, covered with several inches of pure Mississippi muck. A full 700,000 people were left homeless, and 500 others died.

To ensure this would never happen again, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed new levees and pieced together existing ones. This “channelization” of the Mississippi was completed in the early 1930s, fully estranging the marsh from its lifeblood and dumping the rich sediment off the continental shelf.

The wholesale erosion began immediately, but it was slow at first because of the relative health of the marsh. Long and thick barrier islands blocked most storm waves, and fringe marshes absorbed what they missed. Sensitive interior wetlands remained unscathed and largely protected from hurricanes and other of nature’s lesser demons.

But erosion was not — and is not — the only foe of the marshes alienated from their nurturing mother, the Mississippi River. The marshes also began to sink at an astonishing rate of 4 feet per century in many areas.

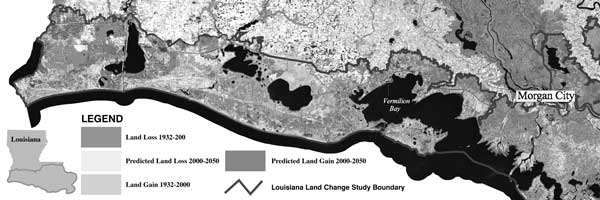

This subsidence combined with the erosion has claimed an exponentially increasing amount of marshland every year since the early 1930s. As the land vanishes, larger chunks of marsh are made vulnerable than were at risk the year before. It’s an accelerating cycle that is very soon going to come crashing down, and for fishermen the consequences will be overwhelming.

For a time, eroding marshes are actually a boon to fisheries. As the marsh in an estuary erodes, its vegetative matter breaks down and suspends in the water as it decays. These microscopic plant parts are devoured by baitfish and crustaceans, especially post-larval shrimp, filling the estuary with large and ever-growing stocks of bait for the next link in the food chain — speckled trout and redfish, among other game fish species.

Also, the erosion of the marshes helps game fish stocks by increasing the amount of edge habitat that specks, reds and baitfish love, according to Rex Caffey, associate professor of wetlands and coastal resources with the LSU AgCenter and Louisiana Sea Grant.

“The break-up of vegetated marsh causes a short-term increase in the ingress routes and edge habitat so vital for juvenile estuarine fish,” he wrote in a study published in 2002.

But obviously, since such an estuary is feeding on itself, its productivity is necessarily self-limiting. Once the amount of land that remains falls below the threshold required to sustain the estuary, productivity plummets.

Some experts believe that sections of Louisiana are already in that collapse phase because, as author Mike Tidwell points out in his book, Bayou Farewell, the rate of erosion has begun to slow in Louisiana.

“Net land loss, which had peaked in the 1980s at about 40 square miles per year, was still going strong at 25 square miles annually in the mid-1990s. The decrease in the rate of loss was due less to human restoration efforts than to the fact that there was increasingly less land left to subside. The coast had tipped toward a final vanishing act,” he writes.

Caffey agrees.

“Indeed, geologic simulations indicate that Louisiana’s coastal land-water interface has recently begun to decline,” he writes.

For years, this decline in edge habitat has been masked by the fact that the eroding and decaying marsh has formed a food base for creatures at the bottom of the food chain, but that’s obviously not a desirable situation.

“What I always ask people is, ‘Do you want a system whose productivity is based on deterioriation or alluviation?’ Right now, for the most part, our system is based on deterioration,” Caffey said. “At some point — I don’t know whether it’s next year or 10 years from now — the system is going to collapse. It’s just a matter of time. We’re eating our seed corn.”

Tipping the scales back the other way will be costly — both monetarily and in shifting of opportunities for anglers. Historical fishing holes may have to be destroyed to benefit the rest of an estuary.

Coastal restoration can be accomplished without ruining the entire sport of saltwater fishing in Louisiana, but it cannot without altering it, according to Kerry St. Pe of the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program.

“We don’t need to destroy fisheries,” he said. “There will certainly be changes, but fisheries don’t have to be destroyed. Quite to the contrary, I think there will be increases; they’ll just be in different parts of the estuaries.”

Flexibility of recreational and commercial saltwater fisherman will be essential if our fisheries hope to have a future that even resembles their past.