Live bait a game-changer in hunt for mangrove snapper

A right hook to the jaw!

Jeff Mire throws a mean sucker punch. The mangrove snappers never see it coming. He hits them right in the mouth — with a live croaker.

Of the 14 snapper species in the Gulf of Mexico, the mangrove snapper has the reputation for being the wariest. Perhaps smartest is a better word. Spear fishermen will dive on an offshore platform and be surrounded by mangrove snapper — until one of them shoots one. Then, they disappear. Next to them, red snapper are regular dumbbells.

Mire, at 47, a veteran offshore fisherman, explains why he likes to use live bait for mangrove snapper.

“Mangroves become leader-shy with any amount of pressure at all,” he said. “I found that if you go to live bait, you can scratch all that.

“I catch a lot of mangroves on 100-pound-test monofilament leaders. That’s something that you don’t see a lot. Using live bait is a lot better option than going to 40-pound-test fluorocarbon. If a big mangrove gets a running start on that and rubs on anything under the rig, you will lose him.

“I catch a lot of mangroves on 100-pound-test monofilament leaders. That’s something that you don’t see a lot. Using live bait is a lot better option than going to 40-pound-test fluorocarbon. If a big mangrove gets a running start on that and rubs on anything under the rig, you will lose him.

“They just can’t seem to resist live bait. I don’t even have to hide the hook. And croakers are the best of the live baits. They are hardier, and they make noise.”

Catching croakers

The afternoon before the trip found Mire and three younger men heading from Port Fourchon out Belle Pass to catch their croakers for the excursion. With him were 25-year-old Justin Martin, his brother-in-law, 20-year-old nephew Nick Mire and 25-year-old Ryan Sholty, a friend

of Martin’s.

“I don’t mind a bit having them to throw the cast net,” Mire said with a grin.

He explained that for some reason croakers that are just the right size for bait bunch up near the beach in the afternoons.

“I don’t know why they aren’t there in the morning, but they aren’t,” he observed.

After exiting the rock jetties at the mouth of the pass, Mire swung his boat, the Lemon Chaser, to the west and behind the rocks. In 7 feet of water, he shut the engine down and drifted.

“They don’t like motor noise,” he explained. “I have never caught them with the motor running.”

It was 5:45 p.m.

Why live croakers

Mire offered constant advice to the three enthusiastic net throwers, and made sure every croaker that came up made it to the big 50-gallon livewell in the back of the 22-foot, deep-V Fishmaster.

“I started fishing for mangroves,” he reminisced, “when I pulled up to a rig with my wife and there were more mangroves than you can imagine. A little Cajun rig worker came down and watched them gobble up every piece of chum I threw, except the ones with the hook in them. ‘Hey, head,’ he croaked, ‘use live croakers, cuz that’s all you gonna catch ’em on.’

“I started fishing for mangroves,” he reminisced, “when I pulled up to a rig with my wife and there were more mangroves than you can imagine. A little Cajun rig worker came down and watched them gobble up every piece of chum I threw, except the ones with the hook in them. ‘Hey, head,’ he croaked, ‘use live croakers, cuz that’s all you gonna catch ’em on.’

“I couldn’t buy them at that time, so I decided to try to catch some. I tried inside [in the bay], but they were too small. Finally, I found that I could catch them in the evenings near the beaches.”

Darkness approached earlier than it should have. Dull, blue-gray, threatening-looking skies were closing in from two directions. By the time the men made it back to Port Fourchon Marina, a drizzle had started to fall. But never mind, the weatherman had a rosy prediction for the next day — 1- to 2-foot seas and a 5- to 10-m.p.h. wind.

They slept like babies.

The next day

Five a.m. revealed that the drizzle hadn’t gotten better; it had gotten worse. It looked like a day of fishing in slicker suits. When the Lemon Chaser hit the open Gulf at the crack of dawn, the sight wasn’t pretty. The sea had a hefty ground roller, topped with an ugly big chop and seasoned with a nasty little cross-chop on top of that.

It was 6 miles to the first stop, South Timbalier 26. The three big interconnected platforms are a well-known destination for mangrove snapper anglers.

After nosing the bow of the boat almost up to each platform, Mire stepped to the bow and tossed some cut-up mullets and croakers near the platforms’ legs. He watched the water carefully to see if any mangrove snapper ran out from under the platform to grab the chum pieces.

Satisfied, he directed one of his crew to ready the rig hook to hook to the platform. The boat was snugged up close to the platform because mangrove snapper are not likely to run a long distance from the security of the platform structure.

“They are frenzy feeders,” Mire explained. “They run out and grab the bait and run back under the platform.

“I only throw enough chum to bring them out, not feed them.”

“I only throw enough chum to bring them out, not feed them.”

Martin quickly connected on a small mangrove. Mire good-naturedly teased him about his catch being a baby, but unhooked it for him and popped it in the ice chest. His eyes twinkled.

Sharks

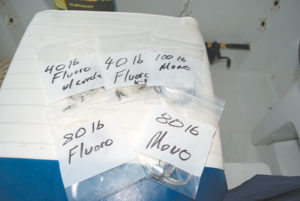

Then the sharks started, one after the other, all blacktips. Mire had to lay his rod aside and spend all his time tying new leaders. The other three anglers were exhausting his carefully laid-by supply of pre-made leaders. Labeled plastic zipper bags held 100-pound, 80-pound and 40-pound monofilament leaders, as well as 40-pound and 80-pound fluorocarbon leader.

As if to add fun to the shark attack, the drizzle turned into a steady rain.

“I can’t tie leaders on fast enough,” cried Mire in disgust. “Let’s quit feeding them.”

In the midst of the miserable deluge, Mire began the 10-mile run farther south, skirting the western side of the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP). When the boat hit 94 feet of water, Mire waved at a group of platforms and well guards, still in South Timbalier.

“We will spend the rest of the day here, moving from that one, and that one and that one,” he said.

After hooking up to the first platform, Mire chummed again, then turned from the bow.

“The mangroves are absolutely here!” he said. “We just got to wake them up and tell them to come out and eat.”

And they set to their task, slipping out of their slickers between squalls and back into them during deluges.

Gear

The basic gear the men used was simple — 6 or 6 ½-foot rods mounting Penn 320 and 330 level-wind reels, each spooled with 40- or 50-pound-test mono. A large 300-pound barrel snap swivel was tied on the end of the line. To this was snapped a ½-ounce to 8-ounce weighted trolling swivel and, separately, the leader. Not having the weighted swivel in line allows for quick change or even complete removal of weights, explained Mire.

The basic gear the men used was simple — 6 or 6 ½-foot rods mounting Penn 320 and 330 level-wind reels, each spooled with 40- or 50-pound-test mono. A large 300-pound barrel snap swivel was tied on the end of the line. To this was snapped a ½-ounce to 8-ounce weighted trolling swivel and, separately, the leader. Not having the weighted swivel in line allows for quick change or even complete removal of weights, explained Mire.

Leaders, regardless of whether monofilament or fluorocarbon, started out at 6 feet long, but gradually became shorter as hooks were cut off and new ones retied. The upper end of each leader had a 200-pound-test swivel crimped on the line. The business end held what Mire described as a “small or medium” circle hook.

Mire was emphatic that his circle hooks must be snelled or power-snelled on the line rather then put on with a knot. Proper snelling, with the line going from the front side of the eye to the back, rather than vice-versa, results in more hook-ups. And snelling, rather than knotting, keeps the line at 100 percent of its rated strength.Each croaker was hooked below and behind its dorsal fin.

Depth

Although, with several people fishing on the boat, every depth was probed for fish, Mire said that fishing for mangrove snapper is conducted, on average, opposite to how it is done for their red cousins. With red snapper, anglers typically drop to the bottom, and if they don’t get any bites, they reel up their baits a few cranks, gradually fishing shallower and shallower until they find the fish.

For mangroves, the rule of thumb is to start shallow, 5 or 10 feet deep, just deep enough so that the bait can’t be seen. If nothing takes the bait, it is gradually fished deeper and deeper until fish are located.

For mangroves, the rule of thumb is to start shallow, 5 or 10 feet deep, just deep enough so that the bait can’t be seen. If nothing takes the bait, it is gradually fished deeper and deeper until fish are located.

The day’s fishing with Mire was enlightening. He showed definite preferences. First, he liked older platforms. Some of the rigs fished were 50 years old. Second, he favored platforms with living quarters. His belief is that food scraps dumped overboard from the galleys above attract and hold fish.

Finally, for mangrove snapper, he showed a strong preference for large platforms with complex structure, over small platforms or well guards, which he believes are fine for red snapper but not suitable mangrove snapper habitat.