This technique is proving ultra-productive in the fish-rich waters off Louisiana’a coast.

A discussion on the Internet reminded me of a problem that has been around for about as long as marine electronics. A fisherman asked for help with his sonar unit’s erratic behavior, and a predictable series of responses appeared.

People who had experienced the slightest problem with a unit built by the same manufacturer (or had some other axe to grind) were telling this poor angler that his fish finder was junk, and he should replace it immediately with their favorite brand, which, of course, was the neatest thing since snelled hooks.

Somewhere near the bottom of the list of responses, a level-headed boater suggested checking the unit’s fuse and fuse holder. The fisherman with the problem reported that the fuse was good, but a bad connection in the fuse holder turned out to be the cause.

Most fuse problems can be prevented. Each piece of electronics lists the proper amp rating for its power line fuse in its owner’s manual. Install a fuse with too high an amp rating, and a unit’s electronics can fry before the fuse blows. Put in a fuse with too low a rating, and it’s likely to blow often during normal operation.

Tubular glass fuses have a metal cap on each end connected by an internal filament. The filament can separate from one of the caps and still look O.K. and even pass a continuity test, but can break the circuit every time you hit a wave. A partial connection can also look and test O.K. but not carry enough current to operate the unit.

The fuse is the first thing I replace when trouble shooting, just in case. I can always reinstall the old one if I find the problem somewhere else.

Units typically come with inline fuse holders that twist to lock and unlock. They rely on spring tension to maintain a solid connection between the contact surfaces soldered onto their wires and the end caps of the fuses inside them.

These holders must be installed with no strain on the wires, and both the holder and the wires should be immobilized. The slightest tugging on one of the wires as a boat crashes through waves can compress the spring and pull the contact surface away from the fuse.

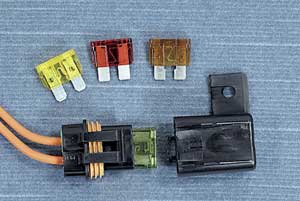

I have replaced many of these with marine-grade holders designed to use automotive blade-type fuses, or done away with the inline fuse entirely and powered the unit from a fuse block.

Most boat manufacturers have either switched to circuit breakers or use fuse blocks designed for flat-bladed fuses. The flat blades plug into spring connections inside the blocks forming a fairly tight fit that reduces corrosion. An occasional shot of contact cleaner out of a spray can followed by a shot of protectant like Corrosion-X on the blades and sockets helps keep them trouble-free.

A surprising number of fishermen don’t bother to learn where their fuse blocks or inline fuses are until trouble strikes. They also don’t know where to find their engine fuses. It goes without saying they don’t have any spare fuses of any kind onboard or any tools that might be needed to change them.

Find your fuses, blocks and inline holders, and do some preventative maintenance on them while your boat is on the trailer. Replace any inline fuse holders that are cracked, broken or corroded. Fuse holders should be installed as close to the battery as possible so they can protect the entire power wire. Stow spare fuses aboard along with any tools needed to replace them. Special non-conducting plastic tools are available for pulling both tubular glass and flat-bladed fuses from hard-to-reach fuse blocks.

Most of all, don’t be one of those poor saps who automatically assumes that his unit is bad, buys a new one and then discovers that it won’t work either until he replaces the $3 fuse holder that’s really his problem.