The fish aren’t exactly giants, but they’re plentiful this month at this Hopedale hotspot.

Capt. C.T. Williams’ web address is thebigfish.net. But during this season of the year, the marshes surrounding his home port of Hopedale deliver not quite exactly what his Internet name implies.

And Williams makes no apologies for it.

“Louisiana anglers want meat,” he said. “We want to fish and fish and fish, and catch and catch and catch. We may be the only people who get excited about 12-inch trout.”

That being the case, the salty air filtering in from one of Louisiana’s farthest-east towns must be crackling with electric excitement right about now.

The winter speckled-trout bite has arrived, and although it doesn’t mean big fish, it does mean plenty of them. Ice chests-full, in fact. More than you’ll need to have ya mom n’ ’em over for a fish fry.

And there won’t be any fighting over the smallest, crispiest fillets.

You know how it is: When you go trout fishing, everyone brags on the way home about who caught the biggest fish, but then when you finally get home and fry them all up, nobody claims the lunkers. The big, chunky fillets are the only ones left on the cold, grease-splotched paper towel after everyone’s belts are unbuckled and their chairs are pushed back.

On the dinner table, it’s the smallest of the small — the 12 1/8-inchers — that receive all the glory. So what if it takes more than one of them to make a po-boy? They’re delicious.

These schoolies are swarming around Hopedale right now, and Williams has the privilege of sitting in a front-row seat and watching the action.

But this is a front-row seat — like those at an Arena Football League game — where he’s actually part of the action.

“I have the greatest job in the world,” he says.

To preview the festivities, Williams took a busman’s holiday recently, and pointed the bow of his big Hydra-Sports bay boat toward one of his favorite wintertime hotspots — Stump Lagoon.

A sleepy December sun rose reluctantly from its nighttime slumber, and cast a brilliant radiance of warmth on the seemingly endless stands of spartina north of Bayou La Loutre. Earth’s nearest star rose slowly and at a distinct angle in the southeastern sky, irrefutable evidence that winter was nigh.

Williams smiled as he sneaked a peak at Stump Lagoon rapidly approaching on his left. Flecks of sunlight sparkled and vanished like spectral diamonds on the barely ruffled surface.

“You know, I love the last three weeks of May, and the type of fishing we have then, but this ranks a very close second,” he said.

He turned into the big lagoon, and throttled down. His boat rose and then quickly settled off of plane. The lagoon looked as beautiful and yet as simple as any others in the area, but Williams knew there were fish there waiting for him. There always are this time of year.

“The pattern is the exact same every year,” he said. “It’s just a matter of when it happens. Cold fronts, water temperature and moon cycle all play a role in dictating that.”

He threaded a curl-tail Berkley Gulp! onto a lightly weighted jighead, and tied it 2 feet below a Cajun Thunder cork. The contraption is a mainstay on Williams’ boat on winter afternoons and on late-fall mornings.

He cast it out, popped the cork a few times, and was soon rewarded by a head-shaking, tail-thrashing speckled trout. It put up a valiant struggle, but it was no match for the 12-pound-test leader. Heck, it wouldn’t have snapped a 2-pound leader. It was a trophy by absolutely no one’s standards.

Until it would be served later that evening.

It went in the box, and would be joined by many similar-sized friends over the course of the morning.

That’s the standard routine for Williams, 48, this time of year. He meets his clients at Breton Sound Marina, makes sure they’re bundled up and runs northeast on Bayou La Loutre.

This major bayou is the conduit for Williams to reach Stump and the other productive lagoons near it, but often La Loutre itself is as far as he needs to run.

“Most winter mornings, the first thing I’ll do is drift La Loutre on the way to Stump,” he said.

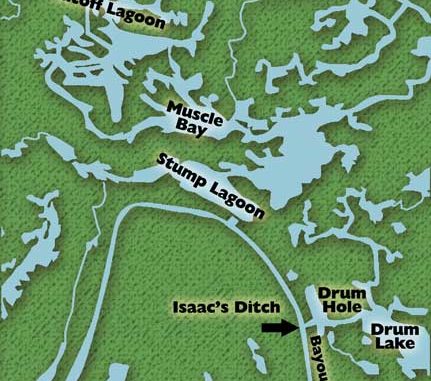

Williams favorite place in La Loutre is between the opening into Stump and Isaac’s Ditch, which is the opening into Drum Hole and Drum Lake.

If the tide is falling, he’ll start at the mouth of Stump and drift toward Isaac’s. If it’s rising, he’ll start at Isaac’s.

“La Loutre is deep, and it’s full of oysters,” he said. “If the fish are in there, there will be plenty boats. It’ll look like Seabrook. But everybody catches fish. You might have a little boat rage here and there, but mostly everybody gets along pretty well.”

Williams rigs blue moon, opening night or magic minnow plastics on 1/4- to 3/8-ounce jigheads, and he simply bounces them behind his boat.

“You want to feel it bounce every five to seven seconds,” he said. “If you feel it constantly dragging along the bottom, you want to take in a little line. If it’s not hitting bottom at all, you need to let a little line out. You want it bouncing on the bottom; you don’t want it digging into the bottom.”

La Loutre is a great place to start on winter mornings because the fish get forced into the deeper water by the cold temperatures of the evening hours, Williams explained.

As the morning warms, the action in the middle of the bayou may slow or stop. If that occurs, Williams will begin casting toward the shoreline, bouncing his baits down the ledge.

“You’ll get a lot of redfish mixed with the trout doing that,” he said. “It’s very possible that we’ll limit out right there in La Loutre, and we won’t even have to go any farther.”

But if the La Loutre bite peters out and there are still a few empty spots in the creel, Williams will turn his attention to Stump Lagoon. The fish that spent the cold night in the sanctuary of La Loutre’s depths will move into Stump with the warming daytime temperatures to try to find some food before sunset again drives them deep.

If the tide is rising when Williams enters Stump, he’ll start his drift near the mouth of Stump, where it enters La Loutre.

“With the rising water, the bait will be forced through that cut, and that’s where the trout wait to feed,” he said. “Fish are lazy. They’re going to congregate where bait congregates, and this time of year, that’s often where large bodies of water funnel.”

If the tide’s falling, he’ll start his drift near the mouth of Mac’s Pass.

But Williams will make a bait change before any lines are cast. Stump Lagoon averages only about 3 feet deep, and tight-lined plastics aren’t nearly as productive there as those bouncing under rattling corks.

Williams is a big fan of the Berkley Gulp! products, so the shrimp-shaped or curl-tail scented plastics are what he usually rigs under the corks.

His leader length varies according to the depth of Stump Lagoon that day, but it’s usually 24 to 30 inches.

Williams won’t stay tied to the mouth of Stump or Mac’s Pass if the action there isn’t fast enough.

“Stump Lagoon is full of oyster reefs, and almost all of them seem to hold fish,” he said. “I just like to drift, and when I get on a few fish, I’ll put down the Power Pole.”

Anglers who don’t have Power Poles installed on their boats would be wise to keep a Cajun anchor tied up and on the bow, ready to be hurled into the water bottom at the first sign of a plunging cork.

When the action slows, the anchor can easily be easily retrieved, allowing the anglers to continue the drift.

The blitzes in action are usually caused by anglers crossing reefs that are holding fish, Williams said.

“The oyster reefs are the key,” he said. “Oyster reefs are slower to change temperature than the mud around them, and because of the darkness of the reefs, they absorb and hold heat.

“Biologists will tell you that even a half-degree change in temperature can be a big difference to a speckled trout.”

The structure and cover provided by the reefs also attracts bait.

“Bait gets really scarce when it’s cold,” Williams said. “But there’s always something on the reefs — shrimp, baby crabs, mullet, sea lice, whatever.”

Drifting across these reefs sometimes delivers fast action; other times, anglers pick up only a handful of fish per drift, but even those handfuls add up when anglers repeat their drifts and focus their attention on the areas that produced on previous drifts.

“You catch five, six, seven fish a drift, and before you know it, you’ve got your limits,” Williams said.

The action will be more concentrated, Williams explained, whenever there is tidal movement because the moving water creates focal points of bait activity.

The size of the fish that bite baits is also increased by tidal movement.

“Small fish are just really aggressive,” Williams said. “They’ll bite anytime, but as a fish grows and ages, it learns to wait for good conditions to bite. It’s going to be a lot easier then.

“A lot of times, we’ll be catching lots of undersized fish, and you start to think there’s not a keeper-sized fish around. Then the tide starts moving, and all of a sudden, everything you catch is a keeper.”

Stump is just one of the productive options available to anglers this time of year. Nearby Muscle and Cutoff lagoons also hold copious amounts of speckled trout and even redfish, black drum and sheepshead during this season.

The only caveat is that the lagoons shut down whenever harsh winter winds blow for several days, but it’s not because the water gets dirty.

“In January and February, the issue is depth,” Williams said. “If the water drains out and it doesn’t come back, you really can’t fish the lagoons. They’re too shallow. But when the water’s in here, the fish are in here.”

Like most experienced anglers, Williams likes to play the fronts this time of year, but he won’t let a mild to moderate front keep him off the water.

“By no means is a front a deal-breaker,” he said. “In fact, sometimes the fishing right after a front is better than a day or two later because the water hasn’t blown out yet.

“We still catch fish here in 20- to 30-m.p.h. winds as long as we still have water.”

Other Hopedale hotspots this time of year are Lakes Amedee and Ameda as well as Hopedale Lagoon, and like Stump Lagoon, they’re all less than a 15-minute boat ride from Breton Sound Marina.

“All those spots have two things in common: oyster reefs with deep channels nearby,” Williams said. “The fish retreat to the deep water when it’s cold and feed on the reefs whenever it’s warm enough for them to do so.

“No matter where you go in Hopedale this time of year, the pattern’s the same. You just need to fish the pattern.”

January’s fish may not be the biggest, but you’ll be grateful for that when you introduce them to Mr. Zatarain.