Learning how to pick apart a jetty can result in hefty limits of trout. And these guides have the process down pat. Here’s how they do it.

It wasn’t the size of the white caps nor the impact they had on the 24-foot bay boat. Both were negligible in the comfort of the ride as we traversed the open water that solid land dominated only 20 years ago — maybe less.

It was what the persistent breeze and correspondent chop represented, or in this case what it didn’t.

“We can forget about those topwater fish now,” said a pragmatic Capt. Lloyd Landry IV, not even slowing or even giving much of a glance to roiling water that churned the bay inside out.

Decades of experience traversing these waters — and sadly too much of that in its current state — had taught him there are good winds and bad winds relative to direction and even strength.

But a wind strong enough in any direction could really only be bad for our goal: finding clean water over acres of oysters in hopes of a brace of speckled trout that would never be erased from a phone’s photo bank.

Topwater hopes might have been dashed, but the nearby Empire jetties gave us the same possibilities for a memorable catch, albeit without the aesthetic thrill of a topside strike.

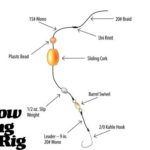

Instead, rods were rigged with 3/8-ounce jigs with either very black or very bright glow chartreuse plastic swim tails.

Cleaner water— but certainly nothing to be considered clean — presented itself as Landry eased the trolling motor down and explained the stark difference in plying the waters that weren’t very far from each other but many, many miles from one another in philosophy.

“This is open-water fishing, whether it’s the swells and the chop from the Gulf, the pogie boats passing by, the current,” said Landry, readying a heavy Danforth anchor on the bow of his boat as he slipped into position as quietly as the foot and a half chop allowed.

It was an utterly, exactly similar expanse of rocks stretching for at least a half mile buttressing the ongoing and hopeful $50 million Pelican Island restoration project to the left, a plan to add three miles of sand dunes and marshland to the backside in Louisiana’s fight to save the coast.

Landry has been fishing these jetties since the ’70s, and has literally seen the surrounding marshland disappear before his eyes.

He’s also fished the rocks at the gateway to the Gulf for as long, and he said finding what’s going on beneath the surface is every bit as critical as looking at what’s happening above.

“When they built them, I’m sure there were some times when a rock or a bunch of rocks fell off the barge while they were placing them in a line,” Landry said. “That’s what you need to find — the little differences in the terrain, whether they’re just off the main line or more out in the open.”

Landry told a story of one of his favorite spots in the entire Buras/Empire system, a place where a once-in-a-lifetime speckled trout is almost always a possibility, no matter how nasty the spring/summer weather is or how dirty the water is.

“I had a guy not too long ago that wanted to catch a big trout and said he would do what it takes to do it,” he said. “The wind was blowing off the Gulf, the water was dirty, but I told him there’s one spot where I thought he could do it.”

Landry was referring to an large, flat rock located just off the main line of the jetty in about 2 feet of water on the edge of a tangle of smaller rocks and rebar.

“I’ve probably caught 15 trout (weighing) 6 pounds or better off of it,” he said. “And I’ve done it even in the worst conditions, if guys are willing to put in the work. That man sat there, and I told him to cast in the same spot over and over again until I said it was enough.

“He cast at least 50 times, lost a bunch of jigs and caught a few 15- to 18-inch fish — nice fish for that day.”

The angler kept at it, even though the fish weren’t the size for which he was looking.

“Then he finally got what he wanted after an hour,” Landry said. “That fish weighed 6 pounds, 8 ounces.”

The charter captain said it’s important to work the structure well.

“What happens is those fish just wait there for some bait to get washed over that rock, where they’re disoriented,” Lloyd said. “They’ll slip up on top (of the rock) real quick for an easy meal and just ease back into position.”

Capt. Chad Billiot, who deals with many other types of rock formations out of Leeville and Fourchon — from Belle Pass’ short set of jetties to the skeletal remains of East Timbalier Island’s, said trout laze in slack areas the water column.

“You’ve got to find the eddies along the line of rocks,” Billiot said. “The primary spots are at the ends where current sweeps past. “

“One of the keys is to find the underwater rocks that interrupt the current as it flows down the line.”

Billiot indicated that such eddies serve to at least loosely congregate baitfish in a general area. Current is always good in moving things along in the life cycle of the area’s dynamic, but a straight-line current is as innocuous as a straight line of rocks.

Billiot said there are subtle clues to finding where these treasures beneath the surface.

“A lot of times the surface will be just a little bit different than usual — maybe a little more of a chop or just a different-looking surface where the rest of the water is choppy,” Billiot explained. “It’s a situation where you really look for at least a little chop on the water.”

Landry said the price he’s paid in mining the big trout that prowl rocks in his region of the state — and countless other smaller trout — is at least 400 jigs over the years.

But that’s a small price to pay for the opportunity for such trophies and a warning for anglers to be prepared to lose plenty of tackle.

“Don’t go out there with just handful of jigs,” Landry said. “And it’s probably a good idea to bring another full spool of line: There are lots of big reds and jacks that can spool you out there.”

Editor’s Note: Capt. Lloyd Landry IV of Outcast Fishing Charters can be reached at 504-912-8291, while Marsh Rat Guide Service’s Capt. Chad Billiot can be reached at 985-637-5058.