Venice’s passes and the ponds between them hold more redfish this time of year than probably any other place on Earth.

As editor of BASSMASTER magazine, James Hall can send an e-mail, select a cover picture and edit a sentence all while on the phone assigning a story to a free-lance writer.

But he’s never had his hands full like he did on a recent trip to Venice.

Hall had cast a gold spoon to the edge of a grass line in a large pond north of Octave Pass when an unseen red darted from the cover, inhaled the spoon and turned to boogie back to its lair.

The veteran bass angler had other ideas, however. He set the hook hard, and the fish responded with a bulldog run along the edge of the grass, ripping line off Hall’s casting reel.

“This fish is SO strong,” the redfish rookie said.

Tired from the trip heading away from the boat, the fish turned and swam toward it.

Only it wasn’t alone. With Hall’s hooked red was a school of no fewer than 50 redfish. Their darting profiles and flashing sides could easily be seen in the transparent, tea-colored water.

They swam frenetically and haphazardly. Some charged at the spoon hanging from the hooked red’s mouth; others bolted to and fro looking for something — anything — to inhale.

Though new to the redfishing game, Hall did what any redfish veteran would — he grabbed another rod from a nearby rod holder, and dangled the bait in the water.

The first red that saw it shot over and inhaled the beetle-spinner, and like a schoolboy going a few rounds with Tyson, Hall had just a tad more than he could handle.

Capt. Ron Price was in the same boat — literally and figuratively. At the first glimpse of the school approaching, he cast into the fray and hooked up, and since opportunity was knocking, he opened the door by casting another bait into the school.

He and Hall now had four fish hooked on four rods held by their four hands. Try reeling with that scenario.

The first fish Hall hooked was now nearing the end of its fight, so Hall stuck that rod between his legs and battled the still-green bruiser with both hands. Against all odds, he was winning the war.

He wore down the first fish, and dragged it to the side of the boat. It was too big to hoist over the gunnel, so Hall, while holding one rod with his left hand and the other between his legs, grabbed the net and slipped it under the exhausted red. He pulled the fish into the boat, and dropped the net, rod and fish on the floor while he finished the battle with the fish on the other rod.

He landed this one with his hands, and looked up to share a laugh with Price, who was trying to land both of his fish without aid of a net.

“I could never live here,” Hall, an Alabama resident, said. “I’d spend all my time doing this. My wife would divorce me.”

Price knows the feeling. Though he’s a guide, and technically a day on the water for him is a day at the office, he just can’t get enough of the spectacular redfishing action that the Venice area offers.

It’s a world-class fishery that is good year-round, but there’s no better time to fish it than right now.

“September and October are prime time,” he said. “If you can fish here before the hard cold fronts blow all the water out, you won’t find any better redfishing anywhere.”

The main reason Venice is so productive in the fall is not difficult to figure out.

During most of the year, the Mississippi River captures massive quantities of run-off — and the sediment and nutrients it carries — from two-thirds of the U.S., and funnels it to the great river’s delta.

The nutrients are like an IV drip of pure vitamins to the entire ecosystem around Venice, with juvenile redfish benefitting from the abundance of bait that eat the zooplankton that feeds directly off of the nutrients. It is, in short, an ultra-rich environment.

In such conditions, however, the ponds and lakes near the river and its major passes are high and dirty. They may be full of redfish, but for anglers, getting the brutes to hit a bait they can’t see is a bit of a challenge.

But beginning in late summer, the river falls below that magical 5-foot number in New Orleans, and the nutrient and sediment loads lessen tremendously. The river, especially on the surface, cleans up, and the water in the ponds gets as clear as an aquarium in many areas.

That’s when reds easily can be seen by anglers, who can watch as the fish dart over to suck in lures. The fish, too, have no trouble seeing baits, and after months of zero pressure, they’re anything but shy.

“In September and October, limits (of redfish) are a foregone conclusion,” Price said. “Those are the gravy train months.”

In the ponds, Price likes to throw the least-expensive weedless spoons he can find.

“The fish will hit just about anything, so why risk losing an expensive bait?” he said.

He’ll blind-cast the spoon in water that’s marginal, but when he can see the bottom in a 10-foot radius from his boat, he’ll hold the lure and only cast at fish he sees.

He’ll frequently run across schools of very bold, aggressive fish that number in the hundreds.

“There isn’t anybody who doesn’t think that’s fun,” he said. “You look out and you see all those redfish running around, looking for something to eat. It almost makes you scared to fall in the water.”

The ponds are typically most productive this time of year during a tide that’s high and falling. Once the tide gets too low, the ponds muddy up a bit, and the water often gets too low for the fish to swim. They’re forced into the passes, where the concentrations of redfish get to be of Biblical proportions.

“There are always reds in the passes this time of year,” Price said. “Any time of day, any tidal condition, you’ll catch your limit of reds in the passes, but after the tide falls out, it just gets sick.”

Many anglers do well fishing the canes that line the passes, but Price shuns the roseau.

“You’ll catch redfish along the canes, but I find they’ve always got their noses right on the canes. If you cast a foot or two off the canes, you’re not going to catch them,” he said.

Instead, Price focuses on the bald stretches of bank that have sandy bottoms.

“You can turn on your trolling motor and work a bald stretch of bank, and catch fish you don’t see, but you’ll also run across a bunch of fish that you can see,” he said. “Usually they’ll be a good ways off the bank, just working that flat.”

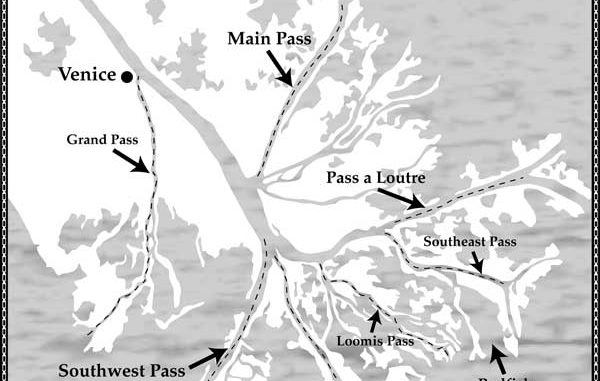

Price employs this technique at the major passes like Main, South, Loutre, Tiger, Grand and Tante Phine, and also at the minor passes like Octave, Joe Brown, Flatboat and Dennis.

“You only want to fish a pass if it’s got clean, green water,” he said. “I look for some type of bait, usually rain minnows. The redfish will be ambushing them; you’ll see wakes moving along the flats and minnows spraying out of the water.”

Also in October, the storm minnows frequently are still present. These cocaho-sized baitfish live in marsh puddles during most of the year, but the high tides brought about by autumn’s storm tides release them from their earthen cages, and they group up in massive schools along the banks of the passes. Redfish gorge themselves on storm minnows whenever they’re around.

“That’s a brain-dead way of finding (redfish),” Price said. “If the storm minnows are around, all you need to do is get a bait in the water.”

Capt. Brent Ballay, who grew up fishing Venice’s passes, agrees.

“When the storm minnows are out, it’s really, really hard to come here and not catch a limit of reds,” he said. “And I’m not talking about fishing all day for a limit. I’m talking about a few minutes or a half-hour.”

Whether fishing in a school of storm minnows or not, Price throws “black/chartreuse Bayou Chubs 99 percent of the time,” he said.

He doesn’t like beetle-spinners for the passes, he said, because the currents are too swift, making it tough to work the baits properly.

“You can’t cover as much water (with spinners),” he said.

Ballay will sometimes harvest the storm minnows with a cast net, and use them for bait. But that really isn’t necessary, he said.

“(The redfish) will hit anything,” he said. “You can throw literally anything you have in your tackle box, and they’ll hit it.”

The action at the edges of the passes is top-notch until the air, and consequently the water, starts getting a consistent, noticeable chill. Then the fish move out away from the edges, and school up on the drop-offs, Price said.

“You’ll find them in 5- to 6-foot depths,” he said. “There’s a spot where Baptiste Collette meets the river that just gets nasty with them. The fish just get stupid. If it’s cold, you’ll catch 50 to 100 in an hour.”

That’s enough action to make anybody want to spend every waking hour on a boat fishing the Venice area.

So don’t tell Hall. His marriage is at stake.

Capt. Ron Price (985-785-0258) and Capt. Brent Ballay (985-534-9246) offer guided trips in the Venice area.