Louisiana has three species of bass that bear bold, black stripes running the lengths of their bodies: yellow bass, white bass and striped bass.

Those three — along with their Atlantic Coast cousin, the white perch (not what we call white perch in Louisiana) — make up the family Moronidae, commonly called temperate basses, an entirely different family than the black basses.

All three gamefish voraciously attack artificial lures and live baits, especially in the cooler months of the year. All three are extremely hard fighters, and pound for pound will outfight a largemouth bass. They just don’t jump as much as their more-glamorous cousin.

Yellow and white bass are more common in Louisiana than striped bass.

When fishermen aren’t busy lumping them all indiscriminately under the name “striper,” these two species are commonly called “barfish.”

Beyond the fact that both have needle-like fin spines, as well as razor-sharp gill covers that can gash a careless fisherman’s hand open, they are distinctly different.

The yellow bass is the smallest in the clan. Although Halbrook’s 2-pound, 10-ounce fish is the largest on record, anything approaching ¾ pound is a good fish in Louisiana.

The species is best identified by its yellow body color, which becomes especially pronounced during its February through March spawning season.

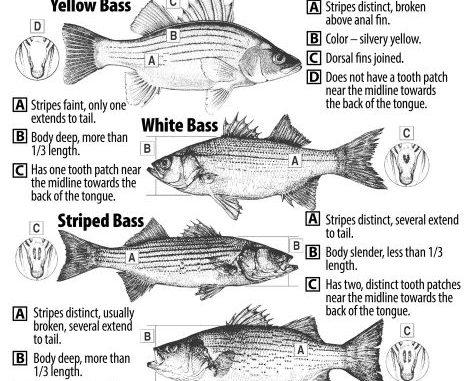

Another distinguishing characteristic it shares with no other member of the family is that the black bars on the lower half of the fish, near the anal (belly) fin, are broken and offset, like an earthquake created a fault line.

The yellow bass seems to tolerate low-oxygen conditions better than its two cousins. It can be found in back-swamp lakes, as well as rivers and reservoirs.

It is the only one of the three that can reproduce with no access to flowing water.

White bass in Louisiana are most common in large rivers and reservoirs, although they will invade almost any overflow habitat in the late winter and early spring when waters are cool and hold a lot of oxygen to gorge before spawning.

Occasionally, like the yellow bass, the black bars above its anal fin can be slightly broken and offset, but the base color between the black bars is white or silver, hence the name.

The body color and the lack of a dependable break in the bars makes the fish similar to striped bass and hybrid striped bass, creating endless confusion among anglers.

An external distinguishing feature that separates the white bass from its cousins is that typically only one black bar will extend all the way to the base of the tail. Hybrid stripers and stripers will have more than one such bar.

A fail-safe way of separating the species is to feel for the teeth on the back of the tongue near its center. A white bass has only one such patch; the other two species have two patches.

White bass grow larger than yellow bass but not nearly as large as stripers and hybrids.

The Louisiana record white bass, a 6.81-pounder caught by Corey Crochet in the Amite River in August 2010, tied the previous world-record fish caught in Lake Orange, Va.

Called “sand bass” or “sandies,” along with several other names, white bass have developed a big following among some anglers. In Midwest reservoirs, schools of white bass force shoals of bait minnows to the surface. In these “jumps” they will take any bait presented to them.

In many places in the eastern United States, anglers look forward to the spring, when the fish mass to make their annual spawning runs up rivers. During these runs, fishermen can catch white bass until their arm muscles burn with fatigue.

Here in Louisiana, we by and large ignore them.

White bass prey heavily on smaller fish, but a live river shrimp impaled on a hook will bring every white bass in the vicinity on the run.

The heavyweight slugger of the family is the striped bass. The IGFA world record is 78 1/2 pounds, although believable reports have been made of stripers of over 100 pounds occurring in old-time commercial fishing catches.

The Louisiana record of 47.50 pounds was caught in 1991. Every striper in the top 10 except one — the No. 9 fish — was taken before 1992.

Presently, a few striped bass can be found throughout the freshwaters of the state, and spawning populations appear to exist in the Atchafalaya and Mississippi rivers.

Striped bass must have flowing waters to spawn. Unlike white and yellow bass, whose eggs sink to the bottom and stick to hard surfaces, striper eggs balloon with water and float, so current is necessary to suspend them while they develop.

While at first glance they seem to resemble white bass, stripers are quite different. Their black stripes are knock-your-eyes-out-bold and run the length of the fish unbroken.

The fish is also shaped differently than the flat-sided white, yellow and hybrid striped bass. It is round in cross section, and the entire fish is distinctly torpedo-shaped.

Adult stripers specialize on feeding on fish, and seem to focus on bright silvery species such as gizzard shad, threadfin shad and skipjack herring (aka slickers).

Like their prey, stripers live in open water and have absolutely no inclination to use cover to ambush their supper like largemouth bass do. At all times of the year, striped bass seem to be attracted to points of water current or current breaks.

The fly in the ointment in temperate bass identification are the striped bass/white bass hybrids. Created by humans, the creatures carry the names “wiper,” “sunshine bass,” “whiterock bass” or “palmetto bass,” and are intermediate in appearance between white and striped bass.

Their bodis are flattened from side-to-side like white bass, but not as much. Their stripes are unbroken like in the striped bass, but they are less bold and more favor those of white bass.

Their maximum size is intermediate as well, with a 16.25-pound fish holding the state record, while the world record logged in at 27 pound. 5 ounces.

Like white and striped bass, hybrid stripers are sensitive to low oxygen levels, and in periods of hot weather will move to deeper waters and almost cease feeding and moving.