Toledo Bend produces massive crappie, but most anglers give up the pursuit during the heat of the summer. This guide knows there’s no better time to fill the box with succulent slabs.

The promise of numbers of crappie rang in my head as I watched Garrett napping across the seats of the big Bass Cat.The boy apparently couldn’t handle the boredom of waiting for a tug on the end of his line any longer, and simply gave up in favor of sleep.

It was hard to blame him: We had moved to no fewer than five submerged treetops with only a couple of fish dropped into the livewell.

John Erickson fretted, since he also recalled his assurances that he would send us home with an ice chest brimming with crappie.

“We just haven’t found the right top,” the owner of Big John’s Guide Service explained. “If that sun would pop out, it would help.”

Yeah, and if I had a stick of dynamite, that would help, too.

After all, the fish were under the boat: I could see them on the depth finder clear as day.

They simply refused to bite our offerings.

It seemed to be a continuation of the early morning bass fishing, which Erickson had bragged about a week earlier.

We did manage a couple of small bass on his favored Lucky Craft Sammy 100s, but it wasn’t stellar.

“The lake has jumped up more than a foot,” Erickson explained then. “That scattered the bass out.”

I didn’t doubt that a big rise in the lake had affected the bass, but I couldn’t help but wonder what excuse he would use if the crappie didn’t begin to cooperate.

Finally, Erickson followed Garrett’s lead and simply gave up.

“Let’s go catch some white bass,” he said, after talking with a buddy via radio.

About 10 minutes later, we took up position over an old, submerged graveyard.

Erickson handed me a rod rigged with a Rinky Dink, a lure resembling a Little George.

An hour later, we had three or four white bass in the boat, and had caught and released numerous yellow bass.

All the while, the sun hid behind clouds.

But as soon as the sky cleared, Erickson was ready to go back to work on the crappie.

“Let’s go look at some tops,” he said, renewed confidence evident on his face.

The first top was loaded with fish, judging from the depth finder.

Not a bite.

We idled to the second top, and out went our baits.

Garrett was settling in for another nap when Erickson snapped his rod tip up and grinned as he fought a nice sac-a-lait to the boat.

As I watched him flip his fish over the gunwale, a sharp tap reverberated up the mono tied to my bait.

The second crappie was soon flopping around on the deck.

Erickson’s son, Shane, quickly added his line to those in the water while Garrett peeked out from under his cap to see if he really needed to get up.

The answer came when Shane and I bowed our rods in unison, fighting two more crappie into the boat.

“I think I’ll fish now,” Garrett said, hopping up and straightening his cap.

Soon, he had joined the fray, pulling in several fish that had devoured the minnows he was soaking.

Erickson smiled in relief.

“Didn’t I tell you that if that sun came out it would help?” he asked.

I didn’t answer, too busy fighting fish to the boat.

Only 30 minutes later, there were about 20 crappie — big crappie — fighting for room inside Erickson’s livewell.

By noon, there were 60 fish in the boat, a couple of them cresting the 2-pound mark.

The key to the successful morning, Erickson said again, was the bright sunlight.

“When it’s cloudy, the minnows scatter,” he explained. “When that sun comes out, it drives the minnows into the tops for cover.”

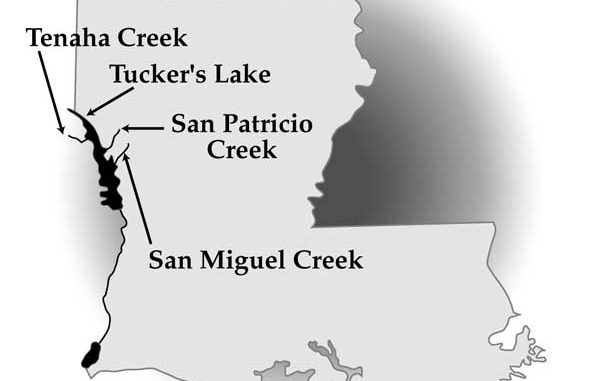

And that concentrates the crappie around the multitude of tops that Erickson has placed around San Patricio and San Miguel creeks.

“I’ve got 100 tops out here,” he said.

That means a lot of time and effort is spent creating these fish magnets, but Erickson said it’s imperative to have as many tops as possible.

“That’s where a lot of people mess up: They put out three or four tops, and if they don’t catch fish on those tops, they don’t have any other options,” Erickson said.

More tops increases the chance of success.

“It’s a matter of hopping the tops to find one where the fish are active,” he said. “If you put out enough tops, you’ll find a top with fish on it eventually.”

That proved true on this trip: If we would only have had a handful of tops, we would have blanked.

But Erickson doesn’t load up any old tops and drop them in random locations. Instead, he carefully prepares each top and chooses its final resting place to provide summer-long fishing.

“I’ve got tops in shallow water, mid-range water and deep water,” he explained.

That’s vitally important because of the very nature of crappie.

“Crappie, perch and white bass are the only fish we’ve got that migrate back into the river system into 40 to 50 feet of water,” Erickson said. “When the weather starts to warm up, they retreat to the first available cover.”

That’s because these fish are some of the most sensitive to changes in barometric pressure and water temperatures.

“Nothing affects crappie as much as the barometric pressure. They get in that deep water, and it doesn’t affect them as much,” Erickson said. “They also move out to find that cooler water.”

His favorite top material is willow, but he admits that the trees doesn’t stand up very well.

“It’ll only stay in the lake a year, and it’ll rot and be gone,” he said.

So he also makes extensive use of cypress and sweet gum, with the former being the most durable.

“Cypress will be here forever,” Erickson noted.

His first step is to cut his tops, carefully choosing trees that have plenty of branches.

“You want a real dense top so the minnows have someplace to get,” he said.

However, he doesn’t put them in the water for a few days.

“I prefer to let them sit until the leaves turn brown,” Erickson said. “The sap that comes out of the leaves and needles and stuff (while it dries), the minnows don’t like it.”

Once a top has turned brown, which tells Erickson the sap is all gone, it’s ready to be placed.

He first rounds up several cinder blocks to use as weights.

“You want to use enough weight to hold it securely in place, even if the lake gets rough,” he explained. “When this lake gets rough, (the water) gets a rocking motion, and if you don’t have enough weight on your tops, they’ll walk away.”

Therefore, he likes to use at least three cinder blocks.

The blocks are tied to the bottom of the top with poly rope.

“You want to use a rope that won’t rot,” Erickson said.

A sealed half-gallon jug or two will then be tied to the top of the tree to keep the structure properly oriented.

“You want the top to stand up straight,” Erickson said. “You don’t want it to fall down on its side.”

A final touch is a sack of bait.

But Erickson’s bait of choice is not what many anglers use.

“People talk about using dog food, but I use alfalfa hay,” he said.

He simply loads a potato sack with the hay, and ties it to the top as far in the branches as possible.

“That alfalfa hay gets green, and gets moss on it, and that’s what the minnows feed on,” Erickson said.

And because the hay doesn’t dissolve like dog food, Erickson’s top is baited for years.

“I never have to bait that top again,” he said.

Next, the entire top is heaved in his boat for the trip to the selected drop zone.

“I set them on the drops, where the bottom drops off from the shallow ledges,” Erickson said. “That’s where the fish travel — on the drops.”

The key to his success is to place each top with an eye toward how much water will be over it.

“I’ll drop an 8- to 10-foot-tall top in 30 feet of water,” he said. “People say, ‘That’s too deep,’ but I point out that there’s only 20 feet of water above the top.”

Another important factor is the size of each group of tops.

“I’ll make tops as big as this boat. I’ll make them as big as possible,” Erickson said. “The bigger the top, it seems, the more crappie you get in them.”

He recognizes that this goes against what a lot of perch-jerkers preach, but Erickson points to his consistent success.

“I’ve made tops with single trees, and I’ll catch six or eight white perch, and that’ll be it,” he said. “We may go to one of my (big) tops and catch 60 or 70.”

Fishing his tops calls for a combination of techniques.

However, there’s one factor all these tactics have in common.

“The key is to keep the bait right above the top,” Erickson said.

Live minnows are his go-to baits, with plastic grubs being used when the fish shut off of the live offerings.

Erickson always packs a lot of shiners in his boat before leaving the dock, knowing that it’s cheaper to have too many than not enough.

“I don’t want to run out,” he said.

He throws the minnows, still in the plastic bags in which they were purchased, in his livewell when he leaves the dock.

A little ice cools his minnow bucket during the ride out, and Erickson said that’s important to keeping the little baitfish alive during the heat of the day.

“That keeps the bucket cool, and that slows down the minnows’ metabolism,” he explained. “They don’t swim around as much, and when they don’t swim around as much they don’t burn as much oxygen.”

But he cautioned that the ice should be dumped out and fresh water added before placing the minnows in the bucket.

“If you don’t, that ice will shock the fish and kill them,” he said.

Although a minnow of any size will catch fish, Erickson said he prefers to root around in the bucket for the smallest specimen he can find.

“I just don’t get the bites on large minnows,” he explained. “Crappie are finicky fish, and they’re more likely to bite a small bait.”

There are even times when dead minnows are productive.

“You can use dead minnows in rough water because they’re moving around,” Erickson said.

Shane Erickson proved that by catching one of the largest fish of the day on a dead minnow.

Erickson’s No. 1 method of fishing a minnow is to dangle it below a slip cork.

“I love fishing with that cork because it keeps the minnow right above the top,” Erickson said.

He said it’s imperative to watch the cork carefully because often fish don’t hammer the minnow and drag the cork under.

“You see how that cork laid on its side?” Erickson said after pulling a crappie in the boat. “A lot of times the fish will hit the minnow and swim up, so the cork doesn’t sink. It just lays over on its side.”

There are times, however, when crappie simply won’t bite a minnow under a cork.

Erickson can’t explain the reasons why. But he’s ready with technique No. 2 — a tight-lined minnow.

The rig has just enough weight to pull the minnow down, with a slipshot being pinched onto the line about a foot above the hook.

“You want to keep that weight well above the hook so that if the weight gets in the top, the minnow is still above it,” Erickson explained.

The trick is to cast the minnow out and let the lure fall to the correct depth.

“I cast it out and count to (six seconds) in 17 feet of water, and then I bump it along over the top back to the boat,” he said. “You just reel real slowly.”

The count might have to be varied up or down, depending upon how much water is over the top.

“If I count to six and I hit the top, the next cast I count to five,” Erickson said. “I count up until I don’t hit the top anymore.”

It’s very important to retrieve the minnow over the top and not in the top, he added.

“If you get hung up in the top several times and shake that top to get unhung, the minnows will run off,” Erickson said.

If that happens, the fishing will slow down drastically, but Erickson said the bait will return and fishing pick up fairly quickly.

“You can come back in an hour or two, and the minnows will be right back in there,” he said.

The one exception to the don’t-get-hung-in-the-top rule is when using plastic grubs.

To make the best use of his favored Stanley Wedgetail Minnows and Mister Twister grubs, Erickson uses a dropshot rig.

A dropshot calls for the weight to be about a foot under the lures.

And to increase his odds of success, Erickson uses two grubs tied about 10 or 12 inches apart.

“Throw it out, and let it sink to the bottom,” Erickson said. “You’re probably going to get hung up, but that’s all part of it.

“That’s where you want it.”

When the weight gets snagged in a top, Erickson lets it sit in one spot and twitches the line.

“Those grubs have such a lifelike action,” he said. “Just twitch that line, and those grubs are hopping around.”

It’s an action that crappie can’t stand.

Erickson’s favorite colors are pink or orange.

“You want something they can see,” he said.

Because he has so many tops from which to choose, the guide doesn’t waste a lot of time trying to force-feed the fish.

“I’ll fish a top for about 15 minutes,” he said. “If I don’t start catching fish after fish, I’ll move.”

But he never moves before trying all three methods of fishing.

“A lot of people don’t understand that when fish shut off on one bait, they sometimes haven’t quit biting,” Erickson noted. “They just want another bait.”

One thing that is sure to send Erickson to another top, however, is the repeated catch of catfish.

“Catfish will run the crappie off,” Erickson said. “They just won’t stay around other fish.”

Even one catfish can shut the fishing down, if proper precautions aren’t taken.

“When you catch a catfish, wipe all that slime off your line,” he advised. “If you don’t those crappie can smell that slime, and they’ll quit biting.”

And worse, other catfish will begin to congregate.

“Every catfish around will smell that slime and ruin the hole,” he said.

And with so many tops to choose from, Erickson doesn’t have to fight that battle.