Avid angler Ray Ohler’s choice of prey belies his social rung.

The Place

Following my GPS, I tentatively nosed my truck through the fortress-like gates of Mariners Cove in Slidell. When the man invited me to hunt alligator gar in the canal behind his house, I had just kind of assumed that the trail would lead me to a rural backwater retreat in the salt marshes between Slidell and Lake Pontchartrain. And Ray Ohler would come out to greet me wearing bib overalls held up by one gallus.

Wasn’t like that, though. This was an upscale subdivision of mansions built around a complex canal network that gave everyone a place to dock his yacht behind his home. Palm trees, short and tall, in at least eight different flavors set the homes off as pieces of a subtropical paradise.

I pulled up to the address, a towering and impressive piece of architecture that seemed to frown down on my casual appearance. I felt like the pizza guy making a delivery to the rich folks.

I rang the doorbell. The chimes echoed through the cathedral-like building like the bonging of Big Ben. No one answered.

“Maybe I have the wrong address,” I thought to myself. I glanced over my shoulder, half expecting a member of the local constabulary to be approaching, ready to question whether I was casing the joint.

Before I retreated, though, I looked through the house (it seemed to be made all of glass) and I spied the top of someone’s head bobbing behind the house. A trip around the side revealed that the top of the head did indeed belong to Ray Ohler Jr.

He extended a hand. Reflexively I did the same — and felt cold glass. His hand held a cold beer for me.

Asking to use his bathroom, I got to see the inside of the house. It was decorated (by his wife Kim) with museum-like care. But in the midst of all the art, hanging over his game room door was a mounted 5 1/2-foot alligator gar.

Yup, I was in the right place.

The Man

On his back deck over the water, surrounded by fishing tackle, I got to know Ohler. At first, he seemed like any other 44-year-old Allstate Insurance Agency (and Mellow Mushroom Pizzeria investor) owner. But the façade soon cracked and revealed a delightfully idiosyncratic individual.

Dominating the fishing stuff on the big deck was the mother of all landing nets. The handle was a 7-foot piece of heavy aluminum pipe with a solid aluminum rim 3 feet in diameter. The netting was a 16-foot shrimp trawl. I asked him about it.

“It’s my garfish landing net. I am usually fishing out here by myself, drunk, late at night … .” He was watching me to see how I would react.

Apparently, I passed the test because he picked up the net and demonstrated how he uses it to land garfish longer than he is tall, by first placing the ridiculously long tail of the net on one piling and then scooping an imaginary hooked fish from the water.

As he demonstrated, then sat down to sharpen the wicked-looking machete that he uses to clean garfish, he repeatedly glanced over his shoulder at the popping cork floating in the canal behind him.

“It’s baited with a chunk of speckled trout,” he volunteered. “Usually, I use shrimp,” he added.

I assured him it is legal to use speckled trout as bait, as long as they were taken legally.

“Even if speckled trout wasn’t legal garfish bait, I wouldn’t give a rat’s ass,” he retorted, not reprovingly. “I’ve got maybe a year left to live.”

I knew that Ohler was diagnosed with stage-four brain cancer in late 2010, but I didn’t expect the openness.

“It’s gonna kill me,” he added with no emotion. “GBM — glioblastoma multiforme is incurable.”

He looked great that day, though — after four brain surgeries.

He answered his cell phone. It was Rusty Munster, his partner in stalking (and eating) garfish, returning his call.

“You forgot?” he barked good-naturedly into the phone. “Whaddaya mean you forgot? I had half my brain cut out. That’s my excuse; what’s yours?”

They are obviously close friends.

After the phone call, Ohler related how he got into garfish. It began when he was rebuilding his Hurricane Katrina-ravaged home (the same one we are at now). He was boiling some big brown shrimp on the back deck for supper.

“Then Nessie came up,” he said. “She looked like she was 8 feet long. I put a u-12 shrimp on a hook on a crusty reel — and I hooked that S.O.B.

“I fought it 40 minutes and didn’t have any way to land it. It was so big that it would come up and rest on the surface. ‘This is crazy,’ I thought, ‘I don’t have anything to land it with.’ I sent my daughter to find something. She came back with a 3-pronged rake. I thought I could jab the tines in it. It was like hitting concrete.

“Then my daughter touched the line with her hand. It was so tight, you could have played it like a harp. It snapped, and I was hooked. I stopped paying attention to rebuilding my house. I bought a tuna [fighting] chair for the deck and stainless steel gaffs. I was catching them from 2 feet to 10 feet long. I fished all night, every day.

“I started doing research on garfish and realized I was catching bigger ones than were the record. Garfish are a closet fish. People won’t tell you they fish for garfish, but they do. It’s like catching a choupique.”

Ohler was working up a sweat, beads as big as marbles popping out of his forehead. His black eyes flashed like a ninja’s between me and his line. He was pacing the deck, waving his arms toward swirls in the canal worthy in size of the Charybdis.

“We had an overpopulation of them after Katrina,” he said. “I couldn’t believe how many garfish we had. I became addicted, and there were no rehab services for garfish addictions. Once you start catching them, it’s insane. I was supposed to be working on the house. My wife was upset with me. People after Katrina were crazy. I had over 60 lawsuits against me [his insurance agency].

“I started a garfish club and limited it to 50 members. They could only fish from my place or my father-in-law’s across the canal. I charged $50. People would be upset because they didn’t get an invite.”

He became almost frantic when a garfish big as a log rose to the surface like an armored submarine, and tantalizingly swirled its spotted tail at Ohler. Then he plunged onward.

“Once, I was fishing back here and I hooked a 10-footer that jumped straight out of the water with 2 or 3 feet to spare,” he said. “It let out a spine-chilling howl.”

He demonstrated a truly blood-curdling yell. I looked around, expecting to see neighbors bolting from their houses. But no one stirred. Maybe they were used to garfish howls.

“I didn’t sleep for days after that,” he said, with his dark eyes fixed on mine. “No one believed me. I got a video camera and before I turned 4- or 5-footers loose, I taped them. They would make noises — not 10-footer yells, but noises.

“I would tell the story at parties and weddings, and I would let out the yell. My wife would get aggravated with me. Garfish caused marital problems for me. I yelled at Kim when she couldn’t get the video camera to work when I had a big one on. She didn’t want me fishing anymore.

“I would sneak out at night.

“I had to lie. She would ask me why I got up during the night. I would tell her I was checking on the dog — whatever.

“I wanted to clean one because everyone told me they were good to eat. I didn’t know how to do it. I looked it up on the internet and sure enough, there are a couple of YouTube videos on it. The summer of 2010 is when I cleaned my first one.”

Then just as suddenly as it began, the ferocious narration ended. A fish had picked up the bait on his rod. It was like watching Ohler move into a zone — a trance. I could feel his concentration, like something concrete, something metallic. He slammed the hook home and the rod slowly doubled into a complete U-shape. It was nothing flashy, just pure prehistoric power.

Then the line broke.

Ohler wasn’t upset. He calmly re-rigged, this time without a cork. While he was rigging, he explained alligator gar behavior.

“They don’t aggressively attack a bait,” he said. “They kind of chew on it. There is a point where they are going to swallow it and you have to set the hook. You have to hook them down in their throat. The mouth is so hard.”

All this is happening while waiting for Munster to leave his office at Toyota of Slidell, an automobile dealership for which he is part owner and general manager.

“We’re going to stick one tonight,” he murmured quietly. “I started bowfishing for garfish after the first year. I got tired of not catching them. I knew I could shoot them. I’m pretty good with a bow.”

He moved back to alligator gar biology, his knowledge of which seems encyclopedic.

“People think that garfish come in and eat all the fish,” he said. “Really, they are basically trash-eaters.”

He cited a Louisiana study that found their main food item was crabs.

He sipped on his beer.

“One thing about garfishing, it’s like shrimping, a drinking activity. That’s what makes it so fun. Catching something that weighs a couple hundred pounds in your backyard. How does that not get to you?”

He slowly stood up, rod in hand. Another gar was mouthing the chunk of bait. I could see the line slowly moving through the water as the fish moved. Ohler’s movements followed the fish — almost Tai Chi-like. But the fish, for no apparent reason, dropped the bait, and Ohler quietly sat down in the settling dusk.

“I like the fish,” he said. “I think they are beautiful — a well-designed animal.”

Yup, I found the right guy.

The Fish

Alligator gar, Atractosteus spatula, are incredibly primitive fish, being around at least 50 million years. Their long snouts provide room for gaping mouths filled with not one row of long, needle-sharp teeth, but two, one row inside the other.

Unlike other fish, which are covered by wimpy cycloid or ctenoid scales or no scales at all, garfish are encased in a flexible armor, like a suit of mail. The interlocking, arrowhead-shaped ganoid scales that make up the armor are hard bone with a layer of enamel over them.

On top of that, they can live in waters that are so oxygen-deprived that other fish would die. In addition to gills, gar can gulp air from above the water’s surface into a lung-like air bladder. This is why garfish are so often seen swirling on the surface during hot weather, when water holds the least oxygen.

Alligator gar, unlike the other Louisiana members of its family, the longnose, shortnose and spotted gar, does well in brackish as well as fresh water, thriving on an abundant food supply of crabs and other crustaceans, as well as fish and anything else that is or once was living.

Besides being the most fearsome-looking fish in North America, they are undisputedly the continent’s largest freshwater fish. The official IGFA world record for rod and reel catches is 279 pounds, a fish caught in the Rio Grande River in Texas in 1951. The largest alligator gar taken by bowfishing is a 365-pound behemoth, verifying multiple commercial fishermen’s claims for 300-pound-plus gar turning up in their nets.

Yup, they’re sea monsters.

The Hunt

With the setting of the sun, Munster appeared. I didn’t hear or see him coming. Just poof! And there he was, out of nowhere, like a vampire. Tall, fair and athletic, the 41-year-old has been a regular fishing partner of Ohler’s since 2003.

And he has his own history with garfish — from the culinary point of view. He has been eating them for 22 years, after being introduced to the fish by friends he made from the Marksville area.

“They serve it there a lot — like people down here eat spaghetti and meatballs,” he said.

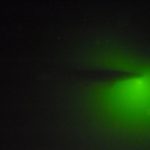

The pair uncased their fishing bows and checked their equipment. The plan was to shoot a garfish from one of the underwater lights that it seems like almost everyone has sunken near their backyard pier. Casting a ghostly, almost phosphorescent chartreuse light up from the depths, they attract fish of all species, redfish, bass, bream — and alligator gar. According to the two, finding the garfish of our choice should be a snap and shooting it even easier.

Unfortunately, Ohler’s light didn’t seem particularly attractive to fish that night. After three or four inspections, he suggested visiting a neighbor’s light. Nothing again. So, back to Ohler’s light. Still nothing.

“We need a boat. We can go to lots of lights,” muttered Ohler intensely. Ohler’s boat, a rugged 21-foot aluminum scow (which he proudly proclaims to be a “Chalmette boat,”) is out of commission.

A cell phone rang. The call was from Todd Melerine, apparently a fellow gar-hunter. He wanted to join the hunt, so Ohler and Munster hung on the back deck waiting for him and watching the glowing fishless orb. The two decided to get Munster’s bay boat from his house to continue the hunt as soon as Melerine appeared.

When Melerine arrived, I learned that the 44-year-old was a certified public accountant and owned his own business, Melerine Wealth Management. He lived in The Moorings, another development of spacious homes in the interconnected canal network.

The three men, with two bows and exuberant spirits, piled into a vehicle to run to Munster’s home in Clipper Estates (yes, another gated development on the Venice-like canal system).

The bay boat was hanging in the cradle behind Munster’s house, seeming ready to go. Except the ignition key had been left on and the battery was stone dead. Even in the dark, one could sense Ohler’s building intensity. He wanted a kill!

So the men visited Munster’s neighbors’ lights. There was something distinctly surreal about three obviously successful middle-aged men, carrying deadly weapons wandering into the backyards of upscale homes in the middle of the night. The result of each visit was the same — zilch. One homeowner, spying us from inside, casually came out as if the event were an everyday occurrence, and informed us that we should have been here yesterday.

Ohler was getting impatient. Even in the dark, I could see his brown eyes flashing.

“We need a boat; we need a boat,” he repeated. “Let’s go to Pete’s.”

Pete was Pete Covignac, Ohler’s 47-year-old uncle and a vice-president and market manager for Whitney National Bank’s Northshore Market. So back the trio went to Clipper Estates. Even though it was 10 p.m., Covignac welcomed them and immediately lowered his expensive fiberglass boat from its sling into the water.

So off they went with Covignac at the helm, bouncing from light to light, looking for the one that held an alligator gar. With so many lights to choose from, this seemed like a sure path to success. It still seemed a little odd and intrusive. As we sneaked up on their lights, the people visible inside their homes were watching the nightly news, unaware of the predators at their back step.

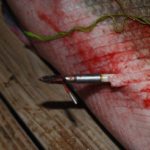

There was one, looking like a log floating above the light. The fish was clearly silhouetted, down to its torpedo-shaped snout. Both Ohler and Munster launched missiles. Munster missed, but Ohler’s arrow ricocheted off the fish’s cast-iron-hard skull. It moved from the light and sulked, preventing another clear shot.

A couple of lights farther down the canal were two more fish, one clearly larger than the other. Perched on the bow, Ohler began excitedly to issue instructions for the approach. Some of them seemed contradictory, and the interpretations provided by Munster and Melerine were clearly contradictory. And the big boat clearly was not designed for micro-maneuvering.

Five passes didn’t spook the larger fish of the pair. Finally, on the sixth approach, the 40-pound garfish was perfectly positioned under the light’s glowing green penumbra. Ohler took the shot.

“I got a hit,” he said calmly without a trace of emotion.

The stricken fish shot under the boat, tangling the line around the foot of the outboard motor, which fortunately was in neutral. Covignac trimmed the motor up and the lithe and agile Melerine clambered out on the motor to untangle the line.

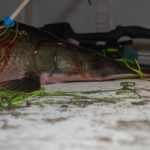

The still lively 40-pounder was yanked into the formerly immaculately white boat, showering it in aromatic feces.

Yup, we had supper.