Largemouths had just about evaporated from Lake Cataouatche in the 1990s, but now the lake is more productive than ever.

Anyone who thinks I’ve got an easy job should have been with me on the morning of my Lake Cataouatche trip. Thunder and gale-force winds woke me at 3 a.m., and it rained all the way to meet Gonzales angler Jamie Laiche for the trek to New Orleans’ West Bank. Most of my “buddies” would have refused to get out of bed. I really wanted to roll over and go back to sleep, but I had to suck it up.

Stupid weathermen had called for the front to roll through the day before, and that would have been bad enough. But here we were driving in the forward fringes of the obvious front from hell with the wind still howling.

However, when we stopped in New Orleans to pick up Jake Impastato Jr., the man was almost giddy.

“We’ll catch them today,” Impastato said. “I’d rather it be like this than blue-bird.”

Although the rain had stopped by the time we made it to the Bayou Segnette State Park landing, it was soon apparent that there was another potential problem: The water was over the road in front of the launch.

“Man, it’s 2 feet high, at least,” Impastato said, still grinning like he was an idiot savant. Almost like he relished the weather.

All I could think was that, judging from my past history, it was gonna be a great day. For those unfamiliar with my luck, re-read the last sentence and add dripping sarcasm.

The only good news is that the winds had inexplicably stopped. There wasn’t even a breeze blowing.

After a short boat ride with all three of us hunkered into heavy rain gear, we arrived at a slick Cataouatche. We made the run across it, slid through the weirs on the west end of the main lake and set up for a run along a bank in the Tank Pond.

Even I had to admit the water was beautiful, despite the days of heavy wind that preceded our arrival. Impastato said the bank was packed with bass the last time he had been there.

“On this side (of the Tank Farm) is a canal, and in the middle it’s about 8 or 9 feet of water,” he explained. “The grass comes up so high, you think it’s shallow, but it’s not.”

Laiche, who competed in the 2008 Bassmaster Classic in February, already had the trolling motor down and was making casts with a spinnerbait.

Before Impastato and I could even get situated, Laiche was setting the hook. The bass wasn’t huge, but it was a fish.

My first cast of the day featured a backlash as big as my fist, but when I finished picking that out and reeled in the slack, I had to set the hook.

“Look at that!” Impastato crooned. “His first cast, and he’s already caught a fish.”

Perhaps the man was more savant than idiot, despite my earlier misgivings.

In the first 15 minutes of the day, five fish had been boated. Over the course of the morning, another 20 to 25 made the trip over Laiche’s gunnel. By noon, we were back at the landing.

That, Impastato said with that same grin he wore when I first saw him that morning, proved just how productive the lake is.

“This place is packed with fish,” he said. “I don’t say this about many fisheries, but when this place is packed with boats, everyone could take home limits and not hurt this fishery.”

The lake hasn’t always been such an incredible fishery, Impastato said.

“It wasn’t a crap hole, but it was close,” he said.

That began turning around a couple of years ago, after the opening of the Davis Pond Freshwater Diversion began pumping Mississippi River water into the lake in 2002.

Impastato said it’s that grass that provides the vibrant food chain on which the bass thrive.

“It makes the water fertile from the base level of micro-organisms up,” he said.

Department of Wildlife & Fisheries biologist Mark Lawson agreed, pointing out that the freshening up of the formerly brackish lake has completely changed the habitat available to bass.

“The diversion is pumping in a bunch of good, fertile water,” Lawson explained. “That’s allowed hydrilla and coontail to really take hold of the lake. It’s just made much better habitat.”

Impastato said the result is a perfect nursery.

“When you get healthy water and healthy plants, you get a real stable environment that you need, and it just turns into an outstanding fishery,” he said.

In response to the changes in the lake, Lawson’s agency has stocked a steady stream of bass into the formerly brackish waters.

“We’ve been stocking Phase II Florida bass (which measure 4 to 6 inches in length) for several years,” Lawson said.

That investment of resources finally paid off big last year, when the lake seemed to explode with bass. While Impastato said the majority of the bass are fairly small, he admitted bigger fish can be caught.

“If you’re looling for an easy limit, Cataouatche’s the place,” he said. “This place is full of fish, but it’s also got plenty of 3-pounders.”

Lawson said sampling hasn’t shown a proliferation of true lunkers, but tournament anglers have been known to put together huge sacks of fish.

“There was a stringer the other day that went 22 pounds,” he said in late March.

Impastato said those heavy bags are rare, however.

“An average stringer is about 10 pounds,” he said. “Typically, to win a tournament, it takes 14 to 15 pounds.”

The key, he said, is to stick with the fish until the big bite happens.

“You have to catch a lot of small fish before you catch the bigger ones,” Impastato said. “After you weed out a lot of those little ones, you might get fewer bites, but the ones you get are good ones.”

Impastato said the annual cycle of fishing the lake is pretty straight forward: Start on the west side of the lake in the shallow spawing waters of what is called the Rice Field, move eastward into the Tank Pond as the vegetation begins to mat and finally, by late April, move out into the main lake on the east side of the Tires (a series of weirs separating the main lake and the Tank Pond).

By May, hydrilla usually begins choking the main lake, and by the time summer really kicks, access is restricted to a few boat lanes.

That’s when the options become rather limited.

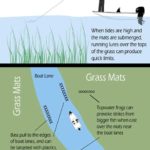

“It’s all about the grass,” Impastato said. “Wherever the grass edge is, where it starts dropping off in the deeper water, that’s where the fish are.”

However, the bite remains hectic.

Lawson said that’s the real advantage to fishermen of the thick mats of vegetation.

“It forces all the fish to the edge of the grass, because they can’t get through that real thick stuff,” he said. “They’re ambushing bait on the edges, so it congregates the fish.”

However, it might take some time to find the fish.

“You can’t just stop any place and catch them,” Impastato said. “But once you find them, they’re stacked.”

In fact, he said it’s almost like speckled trout fishing.

“If you’ve never been to the lake, just look for the boats,” Impastato said. “Once you find where the boats are, you know where the fish are.”

While Cataouatche novices might look at the mats and think punching the grass would be the most-productive tactic, Impastato said that’s not the case.

“It’s not a big flipping place,” he said. “You can take a heavy tungsten weight and punch the grass and catch some solid fish, but it’s not the preferred technique out here.

“You can catch them on other baits a lot easier.”

Skimming a frog across the mats is probably the most-exciting way to catch fish, Impastato said. Zoom Horny Toads and Stanley Ribbits are the best bets.

“When the grass reaches the surface, a frog will catch you some big fish,” he said. “You just fan cast on the mat, and pull it to the edge. Those big fish will get through that mat.”

Weightless plastics also are very effective, as long as the wind isn’t an issue.

“Flukes or (Yamamoto) Senkos are really good baits,” Impastato said. “That Senko is hard to beat.”

If wind becomes a real factor, spinnerbaits work well.

Laiche said he prefers smaller models when fishing these marsh systems.

“I use a ¼-ounce Humdinger,” he said. “I’m a firm believer that bait in a marshy area is smaller, so I think a smaller lure is more natural.”

To ensure he isn’t retrieving the lure too fast, Laiche uses 5:1-ratio reels.

“I use the same retrieve as I use with a 6:1 reel, but my bait is moving so much slower,” he explained.

And lastly, he does a couple of things he believes increases hookups.

“I like to bend the point of the hook to the side a little, and I open up the bend,” Laiche said. “I just think I get a better hook-up ratio.”

Impastato said ¼-ounce buzz baits also are effective when weightless lures are impossible to throw accurately because of the wind.

“You’d be amazed at how many more bites you get on these as opposed to a 3/8-ounce buzz bait,” he said.

However, he customizes his buzz baits to make them more suitable for windy conditions by removing the skirt and threading a curl-tail grub on the hook.

“You can cast it so much farther, even in the wind,” Impastato said.

Although high water often is a killer in many systems, Impastato said it’s a boon for Cataouatche anglers, and opens up new potential.

“I like high water,” he said. “When the water gets over the grass, the fish are so much more likely to come up and bite instead of pushing them to the edges.

“You can just drift over the grass and fan-cast.”

However, what Impastato really likes to do is work the banks while the crowds work the main lake.

“What I look to do is find points along the banks,” he said. “For some reason, the grass won’t grow all the way up to the banks, and there are points were the water is clear.

“The fish will push bait up on those banks.”

He said the same lures are productive here as on the main-lake grass mats.

In fact, that’s exactly how we caught our fish on this day. And it didn’t take long for Laiche to realize the pattern.

“That’s the second fish we caught on a point,” he said only a few fish into the trip. “We’re getting some other bites, but the bigger fish are coming off those points.”

The key to finding productive points is to pay close attention to water clarity.

“You want to have clear water,” Impastato said. “If the wind’s blowing, it can murk up the water along the banks, but when you find a point that has clear water, you’ll usually find fish.”

Impastato said satellite images reveal numerous points, and any one of them could be stacked with fish.

“They look small on the map, but they’re big when you’re moving down the bank,” he said.

Particularly productive are the main points at the mouth of the lake where it meets Bayou Segnette, where the diversion dumps into the north end of the lake (as long as the diversion isn’t running) and on the northern end of Bayou Couba.

“If the fish are on those points, it’s like speck fishing,” Impastato said. “You can catch them on every cast.”