When it’s hot, it’s hot. When it’s not, it’s not.

That’s a pretty good description of Old River.

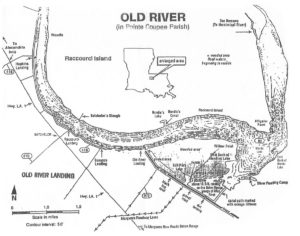

Properly called “Raccourci Old River,” the 4,900-acre lake, once referred to as the “Big Bonanza” by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, is an oxbow of the Mississippi River. (Oxbow lakes are abandoned channels of rivers.)

The Mississippi left nine of them scattered in eastern Louisiana. All of them are narrow and arc-shaped, resembling what they are — old rivers.

But Old River is unique. Unlike seven of its sister oxbows, it isn’t cut off from the big river by levees. So every year, when the Mississippi experiences its spring floods, so does Old River. Dozens of feet of river water will back into the lake, turning it into a catfish hole.

Dave Pizzolato calls it “seasonal” as a crappie spot.

That’s an understatement.

He also calls it one of his two favorite lakes for crappie fishing — and he fishes in a lot of places.

“It’s best from July to December,” he explained. “That’s when the Mississippi River backs out of the lake. Sometimes the water doesn’t get right until August, and sometimes low water lasts until into January.

“Besides flood waters, wind is the biggest limiting factor in fishing Old River. If it’s over 10 miles per hour, the lake is difficult to fish. You can’t place your bait with care, and when you catch a fish, the wind blows your boat yards and yards out of position before you can get your jig back in the water.”

Still, the wiry, silver-haired crappie hound fishes the lake every chance he gets. Here, he shares his expertise:

When to go

Determining when to fish Old River isn’t guesswork. Pizzolato watches river gages, specifically the Mississippi River station at Baton Rouge. A weir at the northeastern end of Old River maintains minimum water levels in the oxbow, no matter how low water in the Mississippi proper falls. But high water in the river overwhelms the weir, backing river water into the lake.

The main boat landing, Old River Landing, (the only other one being Serio’s Landing) is closed at Baton Rouge gage levels of 31 feet or higher, so the lake is by and large inaccessible to boats, except those that venture in through The Narrows, the oxbow’s umbilical cord to the Mississippi River.

Pizzolato starts fishing when the gage drops to 18 feet. At that level, waters are still over the weir, but enough of the structures he fishes are visible above water to begin fishing. Ideally though, he likes the gage reading at 15 feet or less.

The lay of the lake

Shaped like the letter “U,” Old River still bears the marks of the river bed it once was. The strongest current in a river or stream is thrown to the outside of any sharp bend in the riverbed.

Strong water currents naturally are more erosive than slower currents, meaning that deepest waters are almost always found near the outside shoreline of river bends. True to form, Old River retains that trait, with waters 20 feet deep or more very near the southern shoreline of the lake.

This is also the shoreline with road access, so virtually all the camps, located side-by-side, are strung out along the southern and western banks of the lake. And fishing camps mean piers, most of which extend or extended into deep water.

The piers, and even more importantly for Pizzolato, the remnants of destroyed or dilapidated piers, mainly pilings, are the targets of his attention for crappie fishing. Thousands of such pilings exist.

Many of the more modern camps have floating fishing piers that self-adjust to changing water levels. Pizzolato ignores those completely as fish attractors.

Many of the more modern camps have floating fishing piers that self-adjust to changing water levels. Pizzolato ignores those completely as fish attractors.

The northern shoreline, called the “island side” by locals or Raccourci Island, is a raw swampland — one giant hunting preserve. Although a few hunting camps are found there, it holds no fishing camps and their associated piers.

Also undeveloped is the eastern end of the lake, shaped like a giant flexed arm. The deepest spot in Old River at 80 feet is off Alligator Point in Mondu Lake. With its many cypress trees, some in 7 feet of water, Mondu Lake is also a crappie fishing destination for Pizzolato.

Fishing strategy

Dave Pizzolato fishes exclusively with jig poles rather than ultralight spinning reels. “Lure placement is critical,” he explained. “Plus, when I get hung up with an ultralight 25 feet away, I have to go in and get it. That drives me up a wall.”

He carries four rigged Salter’s Jiggin’ poles. Two are on deck, one rigged with a cork; the other without one. A spare for each is kept below deck. Salter’s is the brand he uses exclusively. “I’ve tried others over the years, but I always revert back to them.”

Since the water is so deep where he fishes in Old River, he doesn’t mind crowding a piling, often bringing his bass boat to within a few feet of his target.

Surprisingly, he doesn’t necessarily drop his jigs tight on the pilings he is fishing. Typically, he puts them down 1 to 2 feet from the wood. Whether using a cork or tight-lining, he then moves the jig every two or three seconds with short 8- to 10-inch diagonal or vertical hops.

When tight-lining, he doesn’t just drop the bait to free-fall. Rather he lowers it at a smooth pace with enough control to keep some contact with the lure. If the line develops the least little “curl” in it above water, it means that either a fish has picked the lure up or it has dropped onto some sort of structure.

Line-watching

Because line-watching is so important for tight-lining, he always re-spools his reels with the same 8-pound test Golden Stren monofilament they come with because of its high visibility. Of course, sometimes crappie take the lure with a thump that is telegraphed instantly to his rod-holding hand.

Cork fishing is somewhat simpler because corks are such visible strike indicators. Not every strike with a cork results in the cork going under. Crappie often pick lures up in their mouths without swimming off. Such strikes are indicated by the cork popping up and laying over on its side.

A typical summer day on Old River for Pizzolato may find him fishing early in the morning in shallow water — 3 to 5 feet, with a cork. He doesn’t fish shallower than 3 feet. As the sun rises on the horizon, the fish move deeper and he follows them.

When the water is over 7 feet deep, he lays down his pole with a cork and shifts to tight-lining.

Pizzolato’s boat has a bow pedestal seat, but the bulk of the time he fishes kneeling down, one hand on his trolling motor and the other holding his jig pole. His boat is only 9 years old, but the carpet on his bow deck is worn to shreds, a testament to how often he fishes.

And he nets every fish. Each step is part of a solid routine.

Plastic temptation

Dave Pizzolato bewitches his crappie with two lures, both soft plastics on jigheads. Although he admits to also using Bass Assassin tails, his real workhorses are both made by Bobby Garland Crappie Baits: The 1.5-inch Crappie Shooter and the 2-inch Baby Shad.

In stained water or on dark days, he leans toward darker colors: black and chartreuse; patriot or live minnow. In clear water or on sunny days his preference is for lighter colors such as blue ice, monkey milk or opening night.

These are just his favorites, but he doesn’t limit himself. Pizzolato admits to carrying 15 to 20 colors in his boat at all times and experiments often.

He makes his own jigheads on No. 4 sickle hooks, pouring them to 1/32-ounce. He trims lead off many of these to make 1/64-ounce heads. He uses the smaller heads under a cork, but will use either size when tight-lining.

When he fishes deeper than 12 feet, he goes to the heavier 1/32-ounce heads because the bigger head gets the bait down to the fishing zone faster.

His general preference for use of the smaller jigheads stems from the fact that they fall slower and offer less resistance when fish hit the bait.

Whichever size jighead he uses, Pizzolato tops off his offering with the use of a Bass Pro Shop medium-size hook guard to make the jig weedless. And he always uses the guards — not just when he’s fishing in sunken brush.

A crappie hot dog

Very few people can tell you the exact day they got serious about fishing, especially one with 70 years tucked under his belt.

But Dave Pizzolato can.

“My official start date for serious sac-a-lait fishing was July 4, 1987. I went fishing with my sister Mamie in the Atchafalaya Basin. She is about as serious a sac-a-lait fisherman as a person can get.”

It’s hard to believe that she could be more serious than Pizzolato — if so, she’s got it bad.

After a 20-year career in the U.S. Army, Pizzolato retired to Greenwell Springs, where he pitched into the family business — four large fresh produce markets in the Baton Rouge area.

“I did that until 2010, when I seriously retired,” he quipped. “All I do now is fish, take naps and cut grass. I specialize exclusively on sac-a-lait fishing. It’s not the easiest fish in the world. It’s all about the challenge.”

“And,” he added “they are the best-tasting fish in the world. I love to eat sac-a-lait, especially fried.”

Pizzolato started tournament fishing in 2000 with a club, Louisiana Best. Competing in the South Division, he was awarded Angler of the Year and won awards for the biggest fish of the year and the heaviest (10-fish) stringer of the year.

He still fishes in the non-club tournaments organized by well-known Glenn Davis, averaging one event per month between February and September.

Tournaments aside, Pizzolato crappie fishes an average of twice a week, year-round. He fishes multiple locations and has become a familiar face in noted crappie haunts. “For the most part, the serious sac-a-lait fishermen of South Louisiana know each other,” he grinned.

Tip of the day

Dave Pizzolato discards the plastic pegs that come with his corks and replaces them with the tapered tips of wooden chopsticks. “If the peg comes out, plastic sinks but wood floats,” he grinned.

And Pizzolato is very particular about his corks, insisting on 1-inch foam versions. He special orders them from Grizzly Jig Company in Caruthersville, Missouri.

Pizzolato’s Top 7 tips for Old River

- Learn to tight-line. Using a cork doesn’t allow fishing to be done deep enough to fish the 12 to 14 feet needed on the most important fish-holding structure — piers and pilings in front of camps.

- Use jig poles, not rods and reels. You need the control they offer.

- Not every pier or piling is equal. Some are baited and some are brushed. Some are just better than others. Put the time in to learn them; pay your dues.

- Use solunar tables to narrow your efforts to the best periods.

- Wind is a big factor on Old River. Always fish a spot upwind. Fishing down- or cross-wind doesn’t allow enough boat control to stay on a spot.

- Move a lot to find out where the bite is best. Jig fishing allows that because it is a faster style of fishing than using live shiners.

- This is not a particularly productive place for bank beating. The water in the lake is almost always far too high to fish shallow during the spawn. There are times however, that good catches can be made in mid-summer near cypress trees standing in 5 feet of water.