Opening morning of teal season on the Wax Delta sounds like the beginning of World War III.

Passing over the Calumet Bridge that crosses the Wax Lake Outlet spillway, I glanced south. In the wee hours of the morning, close to the end of the graveyard shift, white stern lights dotted the waterway like the string on a plumb-line as far as the eye could see.

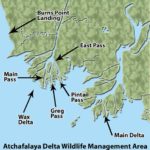

All were heading to the same location — the Wax side of the Atchafalaya Delta Wildlife Management Area.

Glancing quickly north, looking back at the Calumet boat landing, boats were still launching. The parking lot was so full, the overflow of trucks and trailers was trying to find space along the levee all the way out to old Highway 182.

Accompanied by my son David and son-in-law, Chuck Coak, I was glad we made the decision to put over in Bayou Sale. Having to get in line, transfer gear, launch and then go find a place to park, not to mention the long spillway boat ride, was a recipe for big-time anxiety. What’s more, I tend to get impatient as legal shooting light ebbs ever closer.

What was taking place was normal for the teal season opener. Unfortunately, following hurricanes, like Gustav and Ike in 2008, when severe damage has been done to the region’s lush vegetation waterfowl rely on, ducks can be scarce.

Our plan was to put over at a private landing near Burns Point and motor through Hog Bayou to Little Beach Bayou and out into the western end of the management area. Notably, though, we used a private landing. The nearby Burns Point public landing is an excellent alternative for those interested in avoiding opening-day crowds at other public launches.

However, be sure to do some scouting, so that you know where you are going, rather than launching “willy-nilly,” assuming the best. Entering the management area in the dark from the westernmost bay side of the Wax Delta can be tricky; the region is tidal and very shallow.

Additionally, weather can ruin the best-made plans. Hunters should use caution, as westerly fronts pushing through often cause the bay to be extremely choppy. And fog is another consideration altogether different from the aforementioned. Still, don’t rule out Burns Point as an alternative

Two seasons ago, I met Malcomb Dugas after his opening-day hunt at the Burns Point campground, where he and his family were camping and also hunted the Wax Lake outlet side of the Atchafalaya Delta WMA.

“The opener is a chance to get together with family and friends to do a little camping at Burns Point,” the Baton Rouge resident said. “It’s an annual ritual for us. We bring the campers and the wives with us and leave the hassles. It’s also a chance to bring my grandson teal hunting.”

Dugas’ grandson, Luke Dugas, 10 at that time, seemed to enjoy the hunt that morning.

“At first we weren’t doing really good,” he said. “Right after that, we started shooting and we hit some. We started to hit some more, and then about 7:30, we were done.”

What that little fella said were some key words everyone should keep in mind when hunting teal: “finished by 7:30.”

I knew we risked missing the first couple minutes of legal shooting light, if everything didn’t go smoothly. But I much preferred our plan to becoming another bulb in the strand of white-colored Christmas lights heading down the spillway.

We had a pretty good idea where we were going to hunt on the Delta. And most of those white stern lights would essentially hit Main Pass, ultimately splitting off to East Pass, Pintail Pass, Greg Pass and other points east and west.

We’d hunt between the little narrow chutes on the sandbar fingers toward the western edge of the WMA, where some small pond-like open pools of water were surrounded by a sea of grandiose American lotus. The pods and flowers would be our natural blind and cover for this hunt.

Once the first volley of gunfire sounded at legal shooting light and the instant chaotic pressure ensued, the pressure would push the teal toward us as they got out of Dodge. Or at least that’s what I hoped.

Our timing was good. We tied the boat to the bank and walked in land several hundred yards, locating open water in the twilight.

It was quiet, other than the distant droning of a few Go-Devils and late-arriving outboards.

“Hmm, must be lost,” I thought to myself.

Suddenly, from out of nowhere, I heard the swoosh sound of teal sliding into our little pond. Too early to shoot, I strained to see them. My lab apparently could though, as her whistle-like whine was designed to let me know: “Hey Boss, shoot! I’m ready!”

The birds were pretty skittish, becoming unnerved and eventually flew off when I started “shushing” and talking to my dog, explaining to her that it wasn’t time yet.

The last thing I wanted to do was start shooting and become the management area’s official timekeeper. Besides, by the number of boats we saw in the spillway, there’d be plenty of hunters with cell phones lighting up the marsh checking the time. I’d let one of them do the honors.

My son David, off to my left about 20 yards, and son-in-law to my right about the same distance, were quiet — no doubt waiting for me to take the lead.

Funny, my son seemed shorter for some reason. I figured he was already squatting down to hide himself.

The sun was beginning to force its way toward day as slivers of pink light could be seen toward the east. Birds now were beginning to fly everywhere, as we watched their silhouettes against the backdrop of twilight.

The silence was broken when a hunter somewhere couldn’t take it anymore. The whole marsh erupted in a thunder of small-arms fire — the Cajun version of “shock and awe.”

It was fast and furious. Between misses, my son-in-law and I managed to down several birds in the midst of the blue-wing blitz. I wasn’t sure why David hadn’t shot — birds seemingly flew right by him.

“David,” I called out. “Did you see those birds?”

“No,” he replied.

“What the heck’s he doing and where is he?” I thought to myself. “Son, we’ve got birds flying. Where are you?”

“Over here,” he said from his hide.

“All right,” I replied back in the dismissive response dads give when their minds are preoccupied with something else.

We never had any big flocks of teal come in — as I figured. The hunting pressure east of our position broke up the birds. Singles, pairs and small groups steadily came toward us, looking for a place to escape the pressure of steel flack blasted into the atmosphere.

Knocking another bird down into some tall grass, it was difficult getting my dog out on a blind retrieve and signaling where I wanted her to go. I decided to walk over to where I saw the teal go down.

On the way back, I went to check on my son, who was nowhere in sight.

“Where you at, son?” I hollered.

“Right here,” he replied.

As I walked up to him, he had a smile, but had sunk in the sand nearly to the top of his hip boots. Setting my gear down, I pulled him out of the hole and asked how in the world he got stuck.

“I just kept shuffling my feet while standing there waiting, and I kept going down,” he said.

“No wonder you didn’t see any birds,” I said, falling short of scolding.

Come to find out, a similar thing happened to a friend, who also hunted the Delta, when I told him the story. He mentioned he was nearly stuck to his waist with the tide coming in and also needed help getting out. Though the remote sandbars on the refuge are somewhat solid, it’s still new marsh.

The first 60 minutes of daylight are always the best, no matter where you hunt teal. Atchafalaya Delta WMA proved to be pretty much the same. By 8:30, the blue-wing blitz was over. But not before we got our share of birds.