There aren’t many activities that would lure otherwise sane middle-aged men to the swamps when the rest of the state is asleep. Frogging is one of them.

“Kaw, that’s a big one!” said 59-year-old Danny “Eagle” Edgar.

“That’s a man,” agreed 56-year-old Clay Switzer.

“Boy, he really is big,” hissed Harry “Hop” Dugas, who at 47 is the baby of the group.

“It’s got eyes like an alligator,” murmured Edgar in wonderment.

Tense excitement bled through the three men’s Cajun accents.

What could have had them, with nearly 150 combined years of life in the woods and on the water, so excited? Were they perched on a rickety bamboo machan, hunting a man-eating tiger? Were they perched in the flying bridge of an offshore boat, gawking at the massive bulk of a great white shark?

Neither. They were looking at a mere frog — first cousin to the humble hop-toad that parks itself by your patio door to catch the moths attracted to the house lights. Neither a creature of the land nor a creature of the water — an amphibian. Directly related to the first primitive vertebrates that, 400 million years ago, pulled their bodies out of the primordial slop of fetid swamp water onto what passed for terra firma.

But this one was a bullfrog and not just any bullfrog, but a really big one. Bullfrogs make frog legs; one thing that all Louisianans agree on — from Shreveport to Venice — is that frog legs are fine eating.

Edgar steered the airboat to approach the animal, and Switzer held an auxiliary light on the unsuspecting creature. Dugas leaned far out over the bow of the boat, then rapidly thrust his hand down onto the frog and snatched it from its resting spot in the mud and lilies. He quickly popped it through the spring-loaded door of his frog box to join more than three dozen of its fellows already in the box.

The Atchafalaya Basin frogging trip was planned on short notice. The demands of owning a business usually mean that self-employed businessmen make either spur-of-the-moment hunting or fishing trips or the expedition-kind that are planned months in advance. Edgar owns and operates St. Mary Seafood in Louisa. Switzer, from Jeanerette, owns a farm machinery dealership, and Dugas, of Jefferson Island, owns a sand-blasting and painting business.

Switzer and Dugas, who Edgar describes as “like brothers” to him, immediately signed on for the trip a few hours before it was to start, and they agreed to use Dugas’ airboat. The men will also frog out of outboard motor-powered boats, but maintain that airboats have an advantage because the airboat engine’s noise calms the frogs, making them less likely to jump before they can be caught.

Shortly before dark, the three met at the Charenton Boat Landing, along the western guide levee of the Atchafalaya Basin. Quickly, the airboat was skimming the placid, cypress tree-speckled waters of the basin. In the lengthening shadows, enough light remained for every feature, every tree to be perfectly mirrored in the absolutely still water. The air temperature was agreeable. The cold season was well-past, but the torch-like heat of the typical Louisiana summer hadn’t set in yet.

Dugas stopped the boat to wait for dark near an area where Edgar had crawfish traps set. Sitting in the twilight and munching snacks, the men explained that frogging in the Atchafalaya Basin is an 8-month-a-year activity.

Frogging is not allowed during the closed season of April and May. In Louisiana, bullfrogs spawn from March through June, and the closed season was put in place ostensibly to prevent the large spawning aggregations from being hammered too hard by frog hunters.

December and January are just too cold to typically have enough warm days to lure frogs out from their winter hideaways in the water bottom. But the rest of the year can provide good to great frogging. During February and early March, a week of unbroken warm weather will bring bullfrogs out of the mud. With the exception of during unseasonable cold spells, bullfrogs are active in these months, in spite of not calling vigorously.

During February and March, the Atchafalaya River is often at flood stage, and much of the basin in inundated. If the water is warm enough, most of the frogs are caught in and on crusts of floating water lilies (hyacinths) rather than on bayou banks and canal spoil banks.

The June 1 opening of frogging season occurs while bullfrogs are congregated in spawning groups (naturally enough called “frog spawns”). Bellowing male frogs make the classic resonant “brrrwoooom” sound both to mark their territories and to attract females. This singing is most prevalent during spawning season, but occurs all year as long as air temperatures are over 70 degrees.

Typically, June sees the flood waters of the Atchafalaya River receding and the swamps beginning to de-water. During July and August, the drying trend continues, and as the swamps dry up, the bullfrogs in them will travel to permanent lakes, coves, bayous and canals. There they are easy prey for hunters in outboard motors. July and August are typically when Edgar begins to frog in the basin.

September and October are Louisiana’s two driest months, and during this time, the basin’s swamps hold the least water, so even more frogs are forced to permanent water. But frogging activity has also slowed, as outdoorsmen have turned to other pursuits. Knowledgeable froggers do very well in the fall. Switzer says this is, by far, his favorite time to hunt frogs.

November is a transition month, with good frogging in the early part of the month giving way to cold weather and poor frogging by the end of the month.

Dugas started the airboat and moved it at Edgar’s direction out of the bayou and into the swamp’s flooded trees. Edgar, with no light on his head or in his hands, was the designated catcher. When one of the other two men saw a frog’s eyes shine in the dark, he’d waggle the light to indicate “FROG,” and Dugas would guide the boat to where Edgar could lean out of one side of the bow and snatch it up with one hand.

The men picked and poked over the area for more than an hour, and picked up a frog here and a frog there. It was slow, so Dugas killed the boat’s engine, and they conferred. Edgar opined that it was early in the night yet, and there might be a lot of frogs in the area but that they were all underwater feeding at the time.

“I’ve seen lots of times where I would go through an area early and not see a frog,” he said. “Then, when I came back through at 2 a.m., they were everywhere on the surface or on floating logs and lilies. They all have bellies full of crawfish then.”

Another option they considered was that the frogs wanted to be on the bank out of the water, since water temperatures were still relatively cool. The area they were frogging had no exposed banks at the stage the river was. They decided to move to an area that they suspected had exposed mud banks.

Edgar and Switzer exchanged places, which was at the same time good news and bad news for both men. We immediately began to find more frogs — big frogs. But typically they were perched on the bank up under overhanging brush. Numerous stumps and logs also made getting the airboat close enough to make a catch difficult.

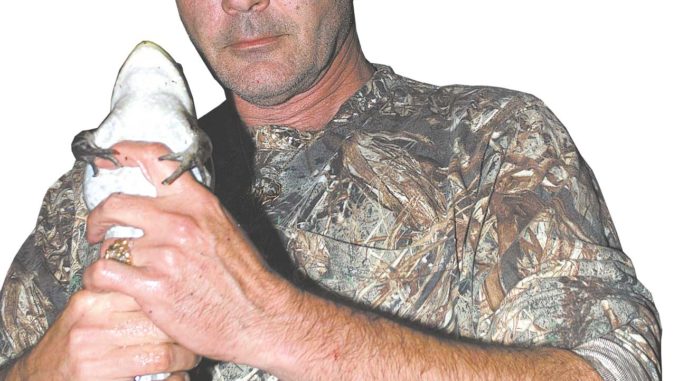

Switzer had to actually kick and fight his way through buttonwood brush tangles enveloping the bow of the boat to get to the frogs. But the frogs were there, and when he got his big hands near a frog, it was lights out for the frog. His smashing grab never missed. Dugas chuckled from his perch and called him “The Claw.”

Often Dugas couldn’t get the boat close enough to frogs because of the brush and logs along the bank, and Switzer had to get out of the boat to try to catch them on foot. A lot of these got away. Frogs are very sensitive to vibrations caused by steps.

Worse than doing hand-to-hand combat with the brush to catch a frog was getting the airboat unstuck from the brush and turned around. Airboats have no reverse. Edgar and Dugas helped, but the lion’s share of that work fell on Switzer.

After Dugas and Edgar felt that “The Claw” was sufficiently wet and scratched up, they called for a break. With the lights and engine off, the feel and sounds of the soft night air enveloped the men. A huge full moon beamed through a stand of healthy cypress trees, a sight that impressed the veteran swamper Dugas. Not a breath of wind existed and there were no mosquitoes.

As they drank their sodas and snacked, Edgar summed up the sight.

“We could have prayed for 20 years and not gotten a better night,” he said.

Neither man disagreed.

For round three, Edgar took over the controls of the airboat, and Dugas did the catching. The lights from the airboat burned holes into the blackness of the night, as the hunt continued. Battling the same brush, Dugas caught as many as Switzer did, only Dugas’ grab was more of a finesse move compared to the smashing power grab of Switzer.

The frogs the men were catching were mostly very large. Some were turbos. Edgar guessed they had 45 frogs in the box. Figuring they had enough for a couple of meals for each man, they called it a night. Back at the boat landing, they counted their catch as they divided it up. The final tally was 46.

The three men shook hands, murmured goodbyes and disappeared into the night, their trucks’ taillights winking through the sugarcane fields flanking the narrow road from the boat

launch.