Huge reservoir was like “Christmas Eve” all season long for duck hunters

Seated across the kitchen table from Mike Benton, I’m struck by the ease in which stories of ducks, duck hunting, and duck calls pour out from the Monroe native.

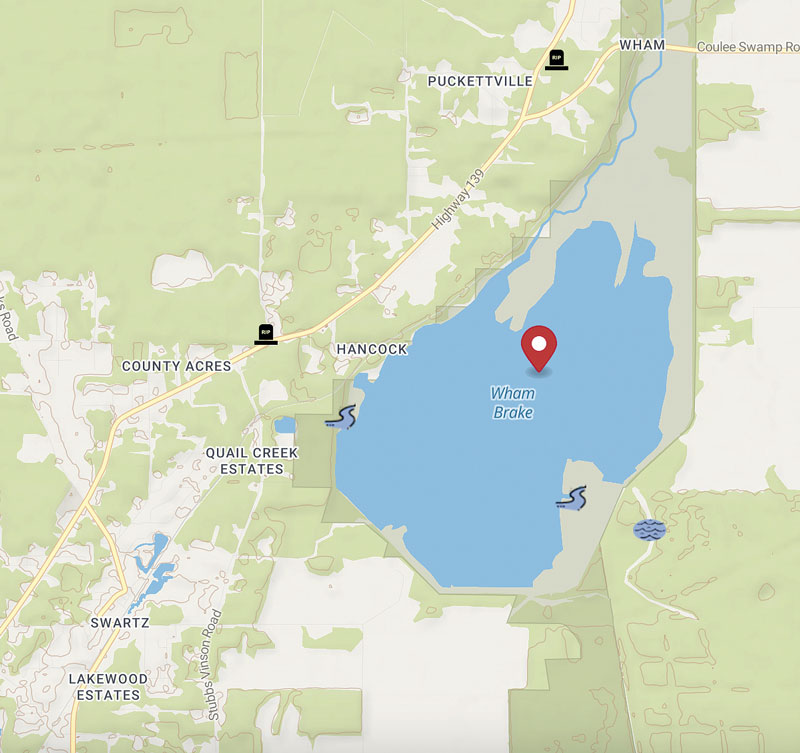

Benton has long been considered to be one of north Louisiana’s best hunters and callers and I found myself soaking in his words. As the interview progressed, I finally took the opportunity to ask about Wham Brake, one of several north Louisiana “holes” that earned a reputation with hunters during the waterfowl glory days of the 1960’s and 70’s. Immediately the smile on his face broadens as he leans into the microphone, almost as if to be sure that what he is about to share is well heard.

According to Benton, “It was like Christmas Eve, the entire length of the season.”

Duck hunting monster

Sometime during the 1950’s, International Paper Company, who used Wham as a final holding area for water runoff from two of its nearby mills, would levee up two thirds of the brake. Historically, Wham would then flood in the winter and gradually drain during the summer, in turn creating some of the best waterfowl habitat to be found in northeast Louisiana.

“It was an absolute perfect setup,” Benton said. “There were cypress thickets and large floating mats of cattails. And when you add that the average depth was only about four foot, Wham was a perfect rest and roost spot.”

At dusk, birds would pour into Wham, and when the local Game Wardens were absent, legend has it that local high school kids would often slip out and shoot long past legal shooting hours.

“Wham was just a magical place that had it all…location, habitat, water.”

One can only imagine today what it must have been like back in the 1960’s and 70’s. The 3,600 acre brake, covered with decoys, and blinds full of many of the best callers from the area, became famous around the South.

“The strategy was really pretty simple,” Benton said. “Each blind would have between three and five hundred decoys out and we would try and put as many good callers as possible in the blind. At that point it became about who was doing the best and loudest calling.”

But the actual hunting at Wham wasn’t the only competitive part of the story.

“One year, we had a long cable on the levee, where you could tie or chain your boat up overnight,” Benton said. “It was a great idea, or so we thought, until we arrived one morning to find someone had stolen the drain plugs from every boat that had been tied up. There were lots of accusations thrown around and even a few fists thrown that morning.”

When the first cut down call arrived at Wham, it was brought by a hunter named Ed Holmes, who discovered the special call while hunting in Arkansas.

“When Ed brought that cut down call back to Wham, he ruled that brake until the secret eventually got out,” Benton said.

Of course, the call Benton spoke of was the cut down Olt, a loud call that would eventually become synonymous with big water and large field success.

The Glory Days

It didn’t take Benton long to lead me into his den, where he retrieved a weathered VHS tape and inserted it into a player. What I saw was something I had never seen with my own eyes, nor will I ever.

“During the 1967 season, someone brought a Super 8 movie camera to the blind and happened to capture what a true migratory flight looked like,” he said.

On the screen were countless numbers of ducks, formed into multiple V’s winging southward. They looked like tiny specks on the screen, but even my eyes could discern what I was looking at.

“Back then, most of the area around Wham hadn’t been converted to rice and beans,” Benton said, “and those birds were all heading to Catahoula Lake, where they would eventually find an area where hunting wasn’t allowed.

“Those ducks would then move between Catahoula Lake and the Arkansas rice fields, many of them flying right over Wham Brake in the process.”

One can imagine what that meant for duck hunters.

Not only did Wham serve as a place for families to fellowship and enjoy ducks and duck hunting, it also provided an education to the next generation of northeast Louisiana waterfowl hunters.

“My brothers and I were super blessed to have grown up hunting Wham, surrounded by many of the great duck hunters from our area of the state,” Benton said. “Harry Williams, Ed Holmes and men like my father made sure that we were taught not just how to hunt, but the right way to hunt.”

Benton went on to share that “sky busting” was severely frowned on, and that the only ducks shot at had to be over the decoys.

“Back then we were shooting 7 ½ shot, so that tells you how close we were getting birds to our spreads,” he said.

But for Benton and his brothers, it wasn’t just about doing what they were told, it was about gaining the respect of the older hunters.

“We wanted to be sure that we were included, to be part of the hunt discussions and that these local masters would continue sharing and teaching us all the things they had learned over the years at Wham,” he said.

A paradise

Of course at the time, Benton, his family or the other Wham Brake hunters could foresee how much things would change in Louisiana for duck hunters.

“Once so many of the fields around Wham were cleared for grain production, things began to change,” he said.

In 2011, Wham was “free leased” to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries before International Paper donated the massive brake to the state, in a deal which also included the fabulous fishing waters of Bussey Brake north of Bastrop in 2013.

Wham eventually became part of the 21,948 acre LDWF’s Russell-Sage Wildlife Management Area located in Ouachita, Morehouse and Richland parishes, providing preservation of wildlife habitat for future generations.

“We were truly blessed to have hunted Wham at a time when it produced both numbers of ducks and a reputation as one of the better hunting spots in northeast Louisiana,” Benton said.

Wham is still an extremely popular waterfowl spot today and although it will never return to its glory days when ducks literally darkened the skies, it is still a great spot to limit out on ducks. Wham is located just north of Swartz and south of Bastrop.

If you plan to hunt Wham, make sure you are current with all the rules and regulations and keep safety in mind at all times.