Dr. James Dickson shares his lifetime of calling experience with Louisiana Sportsman readers.

Out of nowhere, the allure of hunting wild turkeys in spring snuck into my bloodstream one April morning in 1992 over in Alabama.

I had gone along on the hunt because of the invitation of a writer friend, who had set it up. Frankly, I’d have rather been sitting in my boat over a chinquapin bed instead of hunkering on an Alabama hillside that was whitewashed in dogwood blossoms that morning.

When my guide mimicked the hoot of a barred owl and a gobbler answered from the roost, the transition began taking place. Using subtle clucks, purrs and yelps from his mouth call, my guide coaxed the old Bama bird in front of my gun, and I was eternally hooked on the sport.

As I stood over my first gobbler, I resolved right then and there to learn to use turkey calls. As exhilarating as was the conquest of that first gobbler, I developed a passion to do it all myself.

Since that morning in Alabama, I have run off far more gobblers than I ever enticed, but in the process, I have learned a bit about the use of turkey calls — when to call, when to shut up, which calls to use. I have managed to pack out 24 gobblers over the dozen seasons since.

I have ambushed a few birds that didn’t respond to calls, but I have come to the firm conviction that to be a successful turkey hunter, it is essential to master a variety of turkey calls.

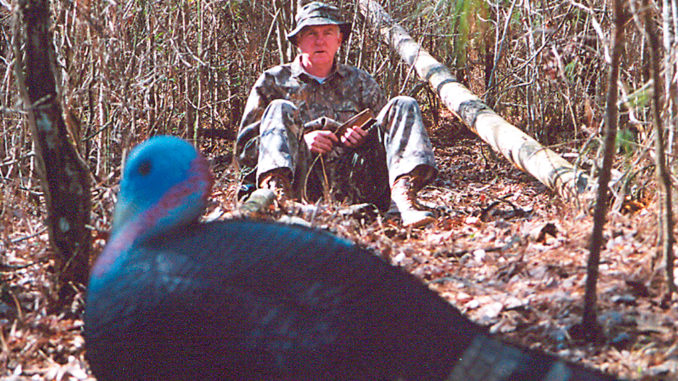

One of the avid followers of the sport of turkey hunting is James Dickson, professor of forestry and coordinator of the Wildlife Program at Louisiana Tech University. Dickson also began writing a column for this magazine last month.

Dickson doesn’t let his string of degrees, awards and accomplishments stand in his way when it comes to hunting wild turkeys. He has hunted all across the country and in Mexico, having taken every subspecies of turkey in the U.S., except for the Osceola, and has added a Gould’s from Mexico. His office walls are lined with photos, stringers of spurs and beards and the mount of his Gould’s gobbler.

I sat down recently with Dickson, 60, to pick his brain about the art of calling wild turkeys.

Dickson has developed a full-blown love affair with these majestic birds, dating back to the first jake he called to his gun during an earlier tenure of teaching at Louisiana Tech in the 1970s.

“There weren’t many wild turkeys in North Louisiana back then, and even fewer turkey hunters,” he said. “Even so, I was fascinated by the prospect of being able to call in a wild turkey, an interest that began while I was a student at the University of the South in the 1960s. I worked at the university library, and one night, I spotted a book on the shelf that caught my eye. It was ‘The Complete Book of the Wild Turkey,’ by Roger Latham.

“I had hunted practically all my life, but there were few wild turkeys where I’d lived before. I didn’t know anybody who hunted turkeys, but as I started reading Latham’s book, I became intrigued by the thought that you could actually interact with a wild creature in the way Latham described. I knew right then that this was something I wanted to learn to do.

“One morning, I slipped out to the woods west of Ruston to give it a try. I’d gotten a couple of calls and had practiced using them, but the test would be to see if it would work on a real bird. I set up and began calling, and to my surprise, I heard a single short gobble. I continued to call, and was startled to hear a cluck behind me; the bird had apparently slipped by without my knowledge.

“I eased around and saw the gobbler looking for me. He stepped behind a tree, and I got my gun up. When he stepped out, I shot him. It was a jake, but the fact that I’d called him up myself was particularly satisfying.”

Dickson left Louisiana Tech in 1978 after teaching two years to take a position as a research wildlife biologist with the U.S. Forest Service in Texas. During the 22-year period before he returned to Louisiana Tech in 1999, his interest in wild turkeys led him to membership in the National Wild Turkey Federation, where he eventually became a director of the organization, served as secretary, vice-president, president and chairman of the board of this 400,000-member organization.

Among his many accomplishments, Dickson has authored several works, including “The Wild Turkey: Biology and Management” and his latest work just released, “Wildlife of Southern Forests: Habitat and Management.”

“While working on my doctorate at LSU, I served as president of the university’s chapter of the Wildlife Society. We had speakers come in for a seminar, and several turkey call manufacturers sent calls to be used at the seminar. I ended up with some calls that were left over. I practically wore them out practicing, but I eventually learned how they worked and how to get the right sound out of them,” said Dickson, a three-time Texas calling champion.

I asked Dickson to name some of the most important things that come to his mind in learning how to call a wild turkey.

“I think that the more types of calls you can learn to effectively use, the better chance you have of pushing the right button to entice a gobbler to come in,” he said. “It is very important that you gain the best knowledge you can of your quarry and how he operates, learn to develop patience and become good at woodsmanship.

“In calling, sometimes almost any call will work. Other times, almost nothing will. During times when gobblers are reluctant to come to your calls, the first thing you need to do is rely on your store of knowledge about wild turkeys and try to figure out why he is reluctant to come.

“Perhaps he has hens with him. If this is the case, it is difficult to call a gobbler away from a hen he is courting. Why should he leave the real thing he has his eye on for one he doesn’t see?

“Later in the day when the hens leave him to go to the nest, he’s much more likely to come in.

“When I encounter a situation where a gobbler is with hens, I’ll try to fire up the boss hen enough that she’ll want to come over and shut me up. If I can get her attention and get her coming to me, I have a good chance at the gobbler that is almost surely tagging along behind. If you can’t get the hen’s interest, however, it can be tough.”

Dickson’s painting a mental picture of a gobbler with hens brought to my mind an occasion where I was able to call a gobbler away from a hen. Once while hunting in DeSoto Parish, I listened to a yelping hen followed by a trio of loud-mouthed gobblers moving away from me through the woods.

I felt my only chance was to create such a ruckus that maybe the hen would come and check me out. I hammered my calls, cutting sharply on a box call while doing the same on a diaphragm. The hen would yelp, and I’d cut her off with raucous cutting.

To my surprise, the four gobblers left the hen and headed my way while she brought up the rear, pleading with “her boys” to return to her. At 25 yards, a red head popped over a log, and I downed a nice double-bearded gobbler.

“The key is to try to process what is going on,” Dickson said when I told him my story. “You tried to become the noisiest, sassiest hen in the woods, and it worked. However, sometimes more subtle calling is required.

“I listen at first light when turkeys begin vocalizing to determine if the gobbler has hens with him. You’ll know it if he does because they’ll yelp, and he’ll hammer back at them. Hens usually cackle when they fly down, and when this happens, he’s likely to leave his roost as well.

“When it is obvious he has hens, you have to get in the game with them and make as much or more noise than they’re making. The key is to try and get the hens mad enough to come run you off.

“Other times, a lonesome gobbler roosted the night before without hens. Your chances at calling him in are usually better than when he has hens. I’ll listen for his gobble, or entice one by using a locator call.

“If he answers and I have him located, I’ll sneak in as close as I dare without spooking him. I’ll call softly to let him know I’m there. If he answers, I’ll shut up, calling only occasionally and softly. Hopefully, he’ll fly down and come in to investigate.”

Some of Louisiana’s best turkey habitat is located on the state’s wildlife management areas. However, turkeys on such areas usually encounter heavy hunting pressure. Dickson has successfully hunted such areas with pressured birds.

“In the 1970s, I hunted Fort Polk WMA in west-central Louisiana. There were a good many birds on the area, but there was lots of pressure. Most hunters would be gone from the woods by 9 a.m., and after that onslaught of hunters, the woods, and the turkeys, would be very quiet.

“I’d just hang around and take my time and eventually, I’d get a gobbler cranked up after he’d had time to settle down.

“Another trick in calling pressured birds is something like playing cards. You don’t show your whole hand at first.

If I have several days to hunt an area, I never use all my calls the first day. I’ll go with a diaphragm, a box or slate and try to work a bird. Maybe I’ll get one to answer, but he is reluctant to come in.

“Since I know where he is, I might set up at a different location and use a completely different call. Sometimes, hearing something different from a different spot will pique a gobbler’s interest to the point he’ll come in.”

I asked Dickson what the mistakes are most novice turkey hunters make.

“Most novices are intimidated by turkeys,” he said. “They lack confidence simply because they haven’t been exposed to the sport and they’re unsure of what to do and when to do it. The No. 1 thing a new turkey hunter should do is to learn as much as he can about his quarry and how it is likely to act and react under a variety of conditions.

“Novice hunters should resolve to become students of the sport. Find out where they roost and where they go when they fly down. Locate strut zones, dusting areas, feeding areas as evidenced by scratching, droppings and feathers. If you know where he is and where he’s likely headed, you have the advantage.

“Learn when to call aggressively and when to call sparingly. You learn this by listening and observing his mood. If he answers me immediately, I’ll back off on my calling because I have his interest. If I know he’s coming, I put my calls down and wait him out. The worst thing you can do is to hammer at him when he’s obviously on his way.

“There are so many variables to calling turkeys. The best way to have a chance to call correctly is to try and get in a gobbler’s head. What is he thinking? What is his ‘temperature?’ Is he interested or nonchalant about the whole deal?

“I think it is the variables that make this sport so intriguing and fascinating.”