More hunters targeting wild hogs at night

The concept of fair chase is a hallmark tenet of hunters around the globe. Basically, it means that hunters give the game they target a fair and fighting chance to outwit the hunter and leave him hungry for another chess match in the field.

But when Jim LaCour enters the woods for his occupation, “fair” is just a four-letter word.

LaCour’s targets are brucellosis, pseudorabies and Lyme disease. They just happen to be carried by wild hogs.

So as the state’s wildlife veterinarian, LaCour uses any tool and every method at his disposal, and increasingly, these options are becoming available to Bayou State hunters.

When LaCour climbed into the bed of his 4-wheel-drive pickup one warm, breezy day last month, the sky was pitch black.

Strike one against fair chase.

Resting on the roof of his truck was a bipod-supported suppressed .308 with night-vision scope and infrared illuminator.

Strike two against fair chase.

And on either side of the Baton Rouge resident were spotters holding heat-sensing optics about the size of the average rangefinder.

Strike 2,756 against fair chase.

But LaCour wasn’t trying to make things fair. In fact, fairness was the antithesis of his goal. Wild hogs have become a serious nuisance in Louisiana, and LaCour would be perfectly happy if they all dropped dead tomorrow.

“Wild hogs transfer and shed bacteria, which impacts the tiniest elements of the food chain,” he said. “They’re the cockroaches of the animal world.

“They also tear up the forest bed so badly that it impacts regeneration. That’s definitely a detriment to the land and the wildlife that lives there.”

And unfortunately, the animals most frequently displaced by hogs are whitetail deer, which have become the kings of the hunting world in the U.S., particularly here in the Deep South.

“Just 15 to 20 hogs can clean out an entire acorn crop,” LaCour said.

Not only that, but hogs actually prey on deer, according to Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries biologist Mike Perot.

“If a hog comes across a fawn, it’ll definitely eat it,” he said.

So land managers like Marty Maley have grown to despise hogs. Maley has invested nearly a quarter of a million dollars into a 3,000-acre chunk of land in East Feliciana Parish that he’s leased for the last seven years.

As Maley has improved the deer habitat, the hogs have taken notice, and have moved in to feast on the goodies.

“In the first three years (that he managed the property), we had no hogs,” he said. “But in a short time, they’ve multiplied and have become very healthy on our property.”

So healthy, in fact, that one of the club’s hunters shot a 300-pound boar during a December deer hunt.

Maley’s heart sinks whenever he walks his land and sees rootings, massive areas where hogs dig up vegetation he’s planted for deer in order to eat the roots.

That’s why Maley was more than happy to let LaCour come onto his property to put even the smallest of dents in the pig population while collecting blood, nasal, stool and tick samples to help increase biologists’ understanding of these invasive animals.

So LaCour and his crew pulled away from Maley’s camp at 10 p.m. on a moonless night with equipment that would be found on Humvees doing night patrols in Iraq. Thompson Creek, swollen from the record Mississippi River heights, had covered 40 percent of the property, pushing the deer and hogs into the woods and fields in the uplands.

The truck was still in the glow of the camp lights when LaCour gave instructions to his spotters.

“Y’all need to start looking,” he said. “They could definitely be this close to the camp.”

The spotters turned on their heat-sensing optics, and within minutes saw the first whitetail deer of the night, which stood unperturbed 20 yards from the truck, looking back at the vehicle with complete indifference.

“You’ll know a hog when you see it,” LaCour said. “It’ll look like a propane tank with legs.”

Within 10 minutes, the crew was passing a pond that is known to Maley to be a hotbed of hog activity, but there was nothing around but a herd of six whitetails.

“Maybe this breeze has the hogs a little spooky,” LaCour theorized. “They might be still bedded down.”

After passing the pond, the crew took a slightly different route back, intending to head toward the southern side of the property.

That’s when one of the spotters let out an excited whisper that is familiar to anyone who’s ever sat perched in a deer stand or duck blind.

“There’s one!” he rasped.

Just 15 feet on side of the road, a 200-pound boar was tearing up the terrain, spewing rich East Feliciana soil 5 feet in the air in an effort to get to the tasty roots beneath the surface. Confident in the cloak of darkness, it couldn’t have cared less that there was a truck within spitting distance on the road.

With normal equipment, the hog had every right to feel so secure. When viewed with the naked eye, the destructive beast was completely invisible. It was a black ghost in a black field on a black night.

But through the heat-sensing optics, it glowed whiter than Breckenridge snow.

LaCour peered through the night-vision scope, and the pig glowed green. While the veterinarian lined up the shot, the hog threw dirt in the air and ripped roots from the ground with its tusked mouth. It wasn’t a dainty process.

LaCour clicked off the safety, and grew perfectly still. Without warning, the suppressed end of the rifle emitted a sharp “pffttt,” and the hog fell quivering.

It was a perfect shot in an unusual place.

“If you aim halfway between the eye socket and the shoulder, it hits the spine every time,” LaCour said.

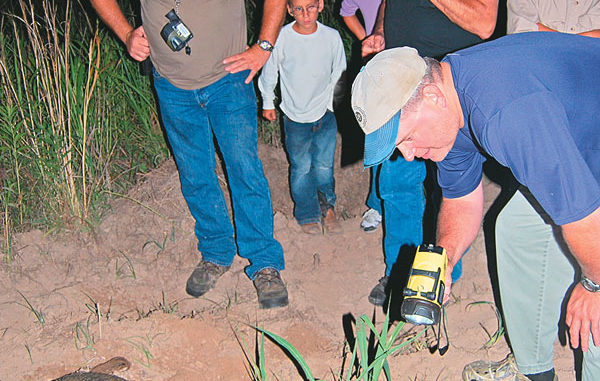

While the rest of the crew rushed to view the fallen foe, LaCour began rummaging through two tacklebox-sized bins, pulling out gloves, syringes and swabs. With his hands protected, he moved toward the pig to harvest the samples that are at the base of every biologist’s knowledge.

He pierced the animal’s heart, sucking out blood samples, and then swabbed the nose.

“You’d think that would tickle,” he joked. “But I haven’t had one complain about it yet.”

Then he whipped out a knife, sliced open the boar’s belly and dug for the stomach.

“Don’t pierce the gut!” one of the youngsters on the trip instructed.

“That’s exactly what I’m going to do,” LaCour responded.

Sure enough, he sliced open the stomach, and the distinctive berry-sweet smell of sour mash dominated the night air. LaCour pulled out a handful of green masticated vegetation.

“Not much in him,” he said. “He must have just started feeding.”

The biologist was looking for turkey poults, eggs or animal parts. Hogs are omnivorous, and will eat just about anything, including other hogs.

“One time we buried some (dead hogs) on Pearl River Wildlife Management Area with a backhoe,” he said. “That night, some other hogs came, dug them up and ate every last piece of them.”

Perhaps the same thing would happen with this 200-pound boar. It was left in the field after it surrendered its samples.

“When we go to get deer samples, we donate the meat to homeless shelters, but I don’t feel comfortable doing that with hogs because of the brucellosis,” LaCour said. “If some worker is cutting up the meat and he cuts his hand, he could be in big trouble.”

The crew loaded back up into the trucks, and traveled no more than 30 yards before one of the spotters eyed three piglets in the road in front of the truck.

LaCour lined up the shot, and dropped one of the piglets. This one was collected by Maley, who threw it into the bed of his truck for later processing.

Things then slowed down considerably, with the group spotting copious numbers of deer, but few hogs. LaCour took a shot on one sow across a field, and the hit and squeal could be heard by all in attendance, but the pig and her offspring ran into an adjacent woodlot. A cursory search yielded no blood trail or carcass, so the team moved on.

After a couple of hours of inactivity, the team turned a corner on a dirt road, and LaCour said, “I smell pigs.” The hunters looked around, but saw nothing. They continued upwind until Dwayne Wheeler, one of LaCour’s spotters, tapped on the roof of the truck, signaling Perot, the driver, to stop.

“Pigs, pigs, pigs!” he whispered.

The hog miners had struck the motherlode. In the adjacent field, 40 sows and piglets feasted on the oats Maley had planted the previous fall for his deer herd.

LaCour had his pick. His crosshairs settled on a sizeable sow that was no more than 50 yards away, and the rifle belched its characteristic “pffft.” The animal fell instantly, and all hell broke loose among the herd, called a sounder in pig vernacular.

“See if any of them stop,” LaCour instructed his spotters.

Pigs ran every which way, and a few stopped for mere seconds, but LaCour was unable to get off another shot.

“All those pigs, and we only got one?” a spotter wondered.

“That’s the way this goes,” LaCour said.

An examination of the sow’s stomach showed it to be jam-packed with vegetation, revealing how much damage a herd of pigs can do to deer habitat. LaCour pulled out several softball-sized handfuls of the stuff, rummaging through it for anything out of the ordinary.

Getting one habitat-annihilating hog out of a sounder of 40 perfectly illustrates why fair chase is just not an option.