Why are south Louisiana waters ‘suddenly’ filled with above-average sized speckled trout this spring? Is dirty water to be applauded?

Why are south Louisiana waters ‘suddenly’ filled with above-average sized speckled trout this spring? Is dirty water to be applauded?

Many anglers in southeast Louisiana have discovered that 2021 has come with a special gift for them, which is, on average, a larger size of speckled trout.

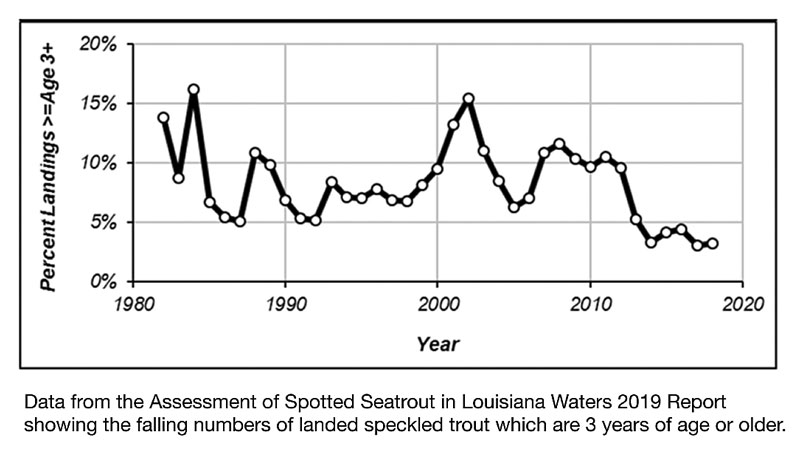

Data from a 2019 survey reported that the percentage of the speckled trout population 3 years old or older had dropped to the lowest levels ever recorded. Not only were fewer older trout caught in the survey nets, but anglers’ landings in this category had fallen below 5% of total landings.

According to aging data collected on speckled trout in the Gulf of Mexico, most 3-year-old female trout are between 15 and 23 inches long. Trout of this size can still be found in schools of similar-sized fish, whereas it is believed that 4- and 5-year-old trout tend to become more solitary. In southeast Louisiana, a 5-year-old trout is not going to have many peers anyway, so being a gator trout would be a lonely existence.

In 2021, the size of the speckled trout I’ve caught has increased noticeably; plenty of them are in that 3-year-old size range. Additionally, I have been catching these fish in quick succession, which indicates the presence of a shoal of trout. This is a change from the past few years, when I would typically only catch one or two 3-year-old trout from a single spot. Anecdotally, I am hearing many other fishermen say they are experiencing similar results.

The abundance of a 3-year-old class of female speckled trout in 2021 is likely not an indication that the spawning stock biomass has magically recovered, but it must surely be a sign of some positive change in the ecosystem. Possibly data from the next trout assessment from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries will shed light on whether we are seeing a significant change.

The abundance of a 3-year-old class of female speckled trout in 2021 is likely not an indication that the spawning stock biomass has magically recovered, but it must surely be a sign of some positive change in the ecosystem. Possibly data from the next trout assessment from the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries will shed light on whether we are seeing a significant change.

Seeing an abundance of these 3-year-olds makes me wonder whether they are here because of an improved spawn in 2018, a decrease in mortality or some ecological change. The measured spawning stock biomass when they were spawned in 2018 was near a record low, so the abundance of 3-year-old females today can hardly be attributed to a record high spawn in 2018.

I have not seen any indication that the harvest of speckled trout has decreased since 2018 and, in fact, it may have increased due to the spike in fishing during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Over the past few years, there has been a grassroots movement not to harvest large fish in an effort to improve the spawning biomass. It would be amazing if that was the cause of the abundance of 3-year-olds, but I suspect the number of trout released was small and could not have accounted for a large class of 3-year-olds already noted in 2021.

What has changed?

What has changed?

However, there has been a major ecological change since 2018 that directly affects speckled trout, and it is an increase in river water flowing into their habitat. While it would be hasty to attribute causation without having supporting scientific studies, I would like to explore the measurable and observable changes that have come with the increase in river water into south Louisiana marshes.

In the middle of May, I took a trip to Delacroix, an area I regularly fished until 3 years ago, in part because of the increased turbidity coming from Mississippi River water bleeding into the area. I recently talked with a friend who said that from January through April, he had caught more than 1,000 speckled trout in Delacroix, despite an abundance of river water stretching from the Mississippi River to Bayou Terre aux Boeufs. The trout landings included many female fish in the 3-year-old size range and a few that were even larger. He said that not only were the trout larger than in recent years, but the number of spring landings exceeded their record spring landings over the past 10 years.

In Delacroix, I found plenty of evidence of a long-term presence of river water, including abundant beds of widgeon grass and a slew of alligators. The water was also turbid from suspended particles, which looked like the silt I see in the Mississippi River at Baton Rouge.

Go with the flow

Go with the flow

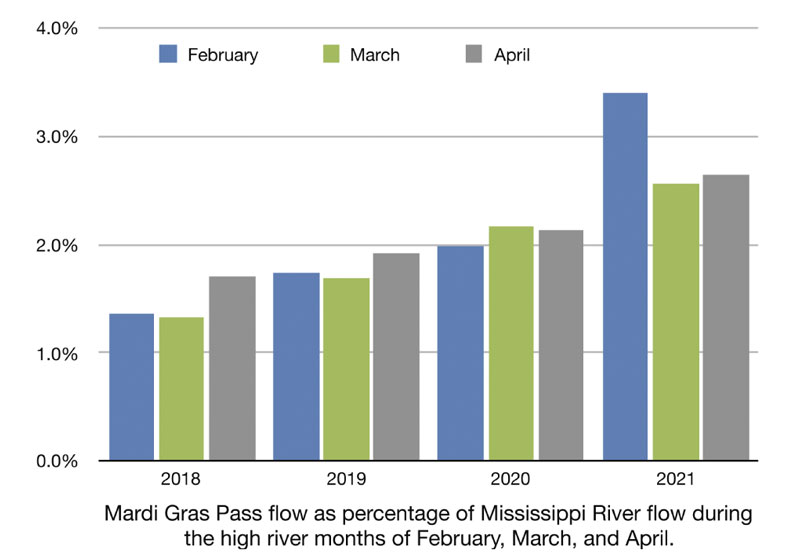

The largest flow of Mississippi River water into the Delacroix marshes is through the Mardi Gras Pass. This accidental levee breach in 2012 near East Pointe a la Hache has been growing each year, and its flow is now equivalent to a medium-sized river. When I stopped fishing Delacroix in 2018, it was having a substantial impact on water quality, and it has grown significantly in flow rate since 2018.

To understand how much it has grown, I plotted the Mardi Gras Pass flow rate as a percentage of the Mississippi River flow rate at Baton Rouge during the high-flow months of February, March, and April. The flow rate through the pass has doubled in 4 years and now discharges as much as 3% of the total Mississippi River volume.

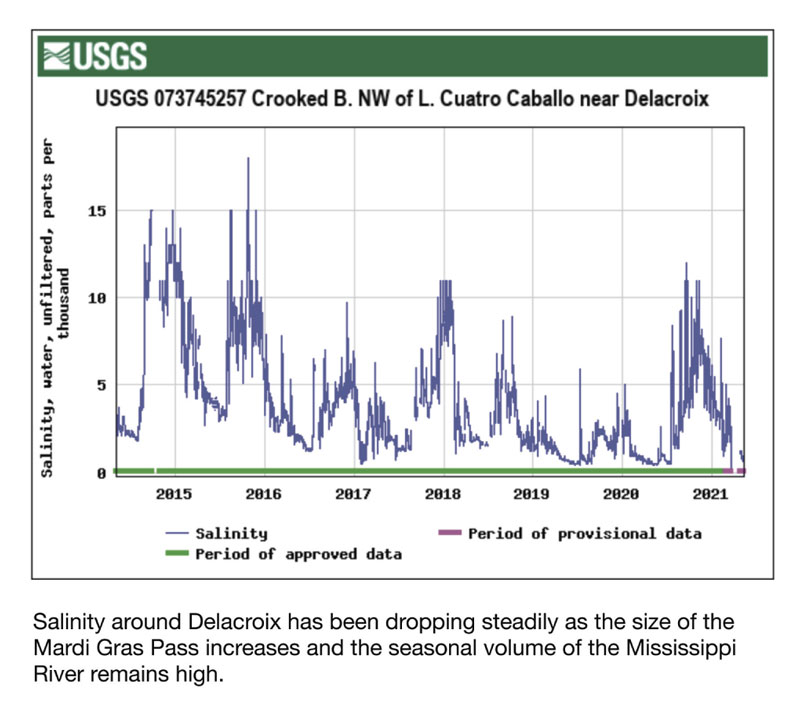

In addition to the silt-driven turbidity, the freshwater from the river has been decreasing the salinity in the marshes around Delacroix. I pulled salinity data from the USGS water quality station in Crooked Bayou near Four Horse Lake from 2014 to May 2021, and the decreased water salinity is quite evident, especially during the lifetime of our current class of 3-year-old female trout.

Let’s not forget the mother of all river-water intrusions, the Bonnet Carré Spillway. This relief valve just north of New Orleans is opened when the Mississippi River height at the spillway exceeds 17 feet, and it can dump as much as 15% of the entire river volume into Lake Pontchartrain.

The Mississippi River has had a record string of high-water years, and the Bonnet Carré Spillway was opened in four of the five years from 2016 to 2020. By comparison, from 1931 to 2015, it was opened only 10 times. During the lifetime of our 3-year-old trout, it was open for 23 days in 2018, 123 days in 2019 and 29 days in 2020.

The morning in May I spent fishing around Four Horse Lake in Delacroix turned out to be my most-productive trip in a month. Roughly 50% of the trout landed were in the 3-year-old size range, and that was from water with clarity of only a few inches. I measured the salinity, and it was around 5 parts per thousand, even though it looked like freshwater recently departed from the Mississippi River. The assumption that water with river silt has low salinity is not necessarily true, since river silt can suspend in brackish water even better than in freshwater.

Down and dirty

My bias against fishing turbid water for speckled trout took a beating that day, because large numbers of trout were feeding there. Clearer water on the east side of Bayou Terre aux Boeufs was just a short swim away, but more trout were being caught in the turbid water of Four Horse Lake.

Similarly, Marsh Man Masson posted a number of videos this spring showing abundant landings of speckled trout in the area around East Pointe a la Hache that was inundated by river water.

We know that aquatic life flourishes on edges. Edges can be formed by structure, drop-offs, current lines, submerged aquatic vegetation and the point where river water and the Gulf water mix. This blending is occurring throughout the coast, including Delacriox and the waters near Pointe a la Hache.

I am left wondering if the recent abundance of 3-year-old female trout spawned in 2018 has any correlation to the river water that flooded into the marshes. At a minimum, we have seen evidence of trout flourishing on the edges of the river-water plume, so we know that the suspended silt is not forcing them away. In fact, some of the females from my mid-May trip were bursting with full egg sacks. They should have been in Breton Sound preparing to spawn, but instead, they were hanging around the edge of the river-water plume in Delacroix.

Are we seeing an abundance of 3-year-olds because they have experienced less natural predation than in previous generations? If they had spent more time in lower-salinity water because of the river-water plume, it would have provided them more protection from dolphins and most shark species.

I have many questions and fewer answers, but I will be watching the size of speckled trout over the next few years to see if we continue to catch larger fish, on average. And, while I wait for answers, I will enjoy fighting these yellowmouths instead of their little sisters.