Most waterfowl hunters and fishermen are vaguely aware that Highway 82, which runs the length of Cameron and Vermilion parishes, follows lines of live oak trees, while much of the surrounding countryside is wide open marsh.

Few give a thought to how these oak ridges, called “cheniers” (chêne means “oak” in French), came to be.

A little investigation will reveal some clues.

They always run east-west, paralleling the Gulf of Mexico shoreline.

A shovel will reveal that the “soil” of the cheniers is mostly sand, with finely crushed sea shell worked into it, much like beach sand. But the nearest beach is often miles away to the south.

Geologists tell us that, indeed, beaches are what cheniers are — ancient beaches stranded in the marsh. And their origins lie with the Mississippi River, far to the east.

Twelve thousand years ago, at the end of the last ice age, sea level stabilized to today’s level. The Mississippi River began carving out the heart of the North American continent and carrying its pieces — sands, silts and clays — to the Gulf of Mexico, where it deposited them.

Some of this sediment load stayed put, building deltas that form what is now Southeast Louisiana. But much of it was dumped into Gulf waters, where prevailing westward longshore currents carried it away.

The great river formed not one delta but many in series, one behind the other. When a delta grew so large that it slowed the river’s discharge, the Mississippi simply bypassed it and took a shortcut to the sea — beginning the formation of a new delta.

Some deltas discharged their load in a generally eastern direction, such as the one that formed the marshes of Hopedale and Shell Beach in St. Bernard Parish.

Others were far to the west. Bayou Tech, for example, was once the channel of the Mississippi River.

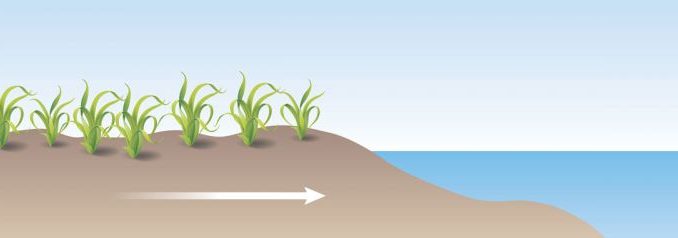

Very little sediment from eastern deltas was available to be swept to the west. During these periods, the shoreline of what is now Cameron and Vermilion parishes would be pounded by Gulf waves, building an elevated beach as it forced the shoreline backwards.

When the river changed its course and began forming western- or southern-oriented deltas, huge amounts of sediment were carried west to be deposited along the same coastline as mud flats, effectively stranding the old beach behind new marsh.

When the river switched back eastward, the cycle started over, and over thousands of years the process produced the complex of oak-studded ridges we know today.